When Twitter first lit up with rumours of an explosion in Bangkok on Monday I did something I’d never previously done during a breaking news event – I turned straight to Periscope.

Finding a stream from the scene of the attack on the Erawan shrine wasn’t difficult. I opened Periscope, clicked on the globe icon, swiped across the map until I got to Thailand and zoomed in on Bangkok.

There I came across a live video stream being provided by an eyewitness called Derek Van Pelt (@dvpme). The stream, titled ‘Bangkok bomb blast aftermath’, was one of three Mr Van Pelt provided from the scene.

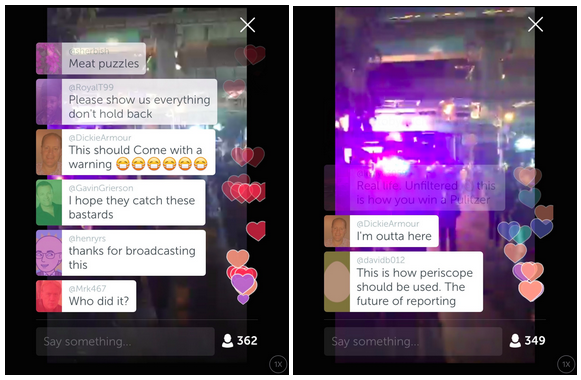

During his Periscope stream, numerous viewers praised Mr Van Pelt for the authenticity of the content he was providing:

“Real life. Unfiltered ?this is how you win a Pulitzer”

“That was horrible but it’s real life!”

“This is more real than news thank u for this”

“This is as real as its gonna get”

As we know from our recent research, authenticity is one of the qualities news audiences most revere about eyewitness media. Our focus group participants argued variously that eyewitness media was more ‘real’, more ‘spontaneous’, more ‘intimate’ and less ‘controlled’ than professional news output.

Crucially though, a number also, and without prompt, spoke of the discomfort they feel from viewing graphic eyewitness media. This, of course, is one of the negative implications of the perceived authenticity, or ‘realness’, of eyewitness media; graphic or disturbing images feel even more relatable, real, authentic and/or intimate when viewed through the prism of an eyewitness’ smartphone.

Watching Derek Van Pelt’s coverage from Bangkok cemented the view that live streaming apps can very easily expose unsuspecting viewers to graphic or traumatic images they may not otherwise wish to see.

By anyone’s standards, the scene left in the immediate aftermath of the Erawan shrine bomb was horrific. Emergency services were diligently attempting to cover body parts with paper towels, but as Mr Van Pelt said during his third broadcast, “There is human flesh just everywhere”.

At one stage the camera focused on what, it transpired, were obliterated body parts. Needless to say it was a highly unpleasant sight. As these comments (replicated without editing, as they appeared in real time) illustrate, commenters’ responses ranged from confusion to shock:

“What is that”

“Omg”

“thats part of someones body”

“I don’t think I wanna know but I’m curious”

“omg”

“that’s a head or other part”

“A head”

“That’s so sick”

“I Just saw red”

“holy shit!”

“What is that?”

“Oh man!”

“that was a head”

[…]

“I’m weirded out now”

At another point, when the cameraman headed towards a crowd of people and inadvertently broadcast another scene of horror, comments regarding viewers’ feelings of discomfort were added into the mix:

“that’s an arm..”

“Holy shit”

“Dear god”

“Whoa”

“Omg”

“What the hell???!!!!”

“Is that a person?”

“What is that?”

“Fuckkkk!!! ???”

“That’s a body? Wow, just a hat and meat left.”

“Jesus”

[…]

“Holy shit”

“not easily horrified. but Fuck”

“OMG I can’t ever unsee that”

Mr Van Pelt’s response, in voiceover, highlighted how difficult it can be to avoid inadvertently broadcasting graphic content. “Sorry, that was disturbing, I didn’t actually know what it was because everyone just gathered around,” he said.

Commenters’ responses to graphic imagery were fascinating. Some people took it upon themselves to forewarn fellow viewers – “Warning graphic footages people !” – although the rapid pace at which comments were being added meant any such warnings disappeared almost immediately.

More generally, the range of feeling – and the varying levels of tolerance – was clear for all to see.

“Don’t need to see that much details mate !!”

[…]

“Yes we do”

Immediately after one viewer had implored the Mr Van Pelt not to succumb to any form of self-censorship (“Please show us everything don’t hold back”), another posted, “This should come with a warning ??????”.

Almost immediately came the somewhat unsympathetic advice, “You can end the broadcast if you don’t want to see it” (this is true of course, but as the viewer cited above had stated, one “can’t ever unsee that”).

This was followed by direct replies to the complainant: “it’s in the title”, “it’s not TV mate this is real life”. Responding to the former, he said, quite justifiably, “it’s not in title. It says aftermath of bombing.” Either way, he’d seen enough: “I’m outta here”.

Later in the day, Mr Van Pelt’s third, and most graphic, stream was awarded ‘Featured’ status on Periscope’s launch page, resulting in upwards of 100,000 ‘replay viewers’.

By this point, the title had a warning appended “Bangkok bombing aftermath [WARNING: GRAPHIC]”. Viewers of the original stream — some of whom appeared disturbed by what they witnessed — were not afforded any such warning, of course.

But when it comes to live streaming is such a warning even possible?

Periscope cannot reasonably be expected to add a warning. After all, it cannot monitor or predict the content of every stream broadcast via its platform. Mr Van Pelt didn’t necessarily know he would be broadcasting such graphic imagery. (In this instance, some commenters rebuffed the suggestion that a warning was even necessary, given the subject matter: “You looking at a bombsite. What did you expect?”)

Also pertinent are the potential psychological implications of being exposed to graphic or traumatic imagery. This applies to both producer/eyewitness and the audience.

Did the encouragement and appreciation from his audience (at one point he thanked viewers for the steady stream of ‘hearts’, Periscope’s equivalent of Facebook ‘Likes’ or Twitter ‘Favourites’) led Mr Van Pelt to subject himself (first-hand) – and, by extension, his viewers (second-hand) – to gruesome sights to which he might not otherwise have exposed himself had he not been broadcasting?

When handling graphic or traumatic content in a professional setting, trained journalists are able to make a judgement call on what can or should be presented to the audience and what must be left on the cutting room floor.

Additionally, there is recognition (in some quarters at least) that exposure to such content can have a negative impact on journalists’ psychological well-being, resulting in the introduction of individual counselling services. This phenomenon, otherwise known as ‘vicarious trauma’ is the subject of a study we are currently conducting. You can read more about it here.

Combined, this means that audiences aren’t (or shouldn’t be) exposed to the most graphic content and journalists handling such material have support mechanisms to fall back on if they feel adversely affected.

Neither of these hold true with eyewitness media. And in both cases, without forewarning or education, the potential for harm might not be recognised until it’s too late.

So who, if anyone, is responsible for any repercussions Derek Van Pelt or any of his viewers may experience down the line? Periscope/Twitter? Mr Van Pelt himself for not exercising sufficient self-restraint? The viewers, many of whom were actively encouraging him to continue broadcasting and, in some cases, egging him on to find more maimed victims?

It’s hard to say. But these are the questions we need to be thinking about because as this technology spreads and evolves they are only going to become more pertinent. News organisations have a duty of care to employees covering traumatic news events and the audience consuming the resulting coverage.

Any suggestion that the same rules needn’t apply to smartphone-wielding eyewitnesses who find themselves at the scene of a news event were neatly (albeit inadvertently) addressed in a comment exchange during Derek Van Pelt’s broadcast from the Erawan shrine:

“R u a reporter?”

“Now he is”