Eyewitness media played a crucial role in reporting the attack on the Paris office of Charlie Hebdo last Wednesday and the shootings that continued over the next few days. But there are some questions to be considered around the speed and sensitivity of how some of it was handled. In the first of a series of blog posts, we try and put ourselves in the shoes of the eyewitnesses.

Those of us who routinely use social networks for information during breaking news events compulsively searched and clicked in an attempt to make sense of what was happening. Our newsfeeds quickly filled up with Vines, Instagram clips and photographs on the #paris and #hebdo hashtags and many of us viewed at least one video that we wish we had never seen.

Much of this raw footage captured the horror and chaos of an extremely volatile situation and through eyewitness lenses we watched as the tragedy played out. From early scenes of a pedestrian running from gunfire and hiding between cars to the shocking video showing the brutal murder of a police officer.

The sophisticated monitoring tools and techniques now employed by breaking news journalists meant that this footage was discovered and shared around the world within minutes of it being posted and the value of this contribution is not in question. It forced us all to take notice. We felt, in some small way, connected to the victims and witnesses. We could not look away

What compels someone to capture and upload a terrifying moment they have experienced is a fascinating topic in itself. For those who routinely document their lives on social media it would be instinctive. Others may feel bound by a moral duty to inform, some knowingly take on a role of a citizen reporter but many would assume they were only updating their immediate followers and friends.

Whatever the motivation, we can be confident that most eyewitnesses have not received journalism training. They are much less likely to think about gaining consent from the subjects in their photos and videos, or protecting their right to anonymity. They probably won’t have considered the implications of sharing graphic content. They are unlikely to think about the steps to take regarding their own safety. They do not have an editor or producer who can guide them through making appropriate decisions and alert them to the potential risks. Legal policies and ethical guidelines don’t feature in their decision to publish.

And it is publishing, of course. But eyewitness media rarely stays under the control of the original owner for very long. The video that captured the killing of a police officer was posted to Facebook but then taken down again soon after, but its swift removal did nothing to deter those who had already downloaded the footage. Newsrooms across the world seemed to unilaterally decide that the video was in the public interest, so gaining permission from the original source no longer appeared to matter.

This fascinating interview reveals that the eyewitness, Jordi Mir, regrets his decision to post the video to Facebook. He explains that he turned down the opportunity to sell the footage and only authorised the AP to use the video if they cut the scene of the officer’s death.

Although some news outlets ran an edited version and some chose to pixelate the policeman’s body, others ran the video in full and many, many more linked to various versions posted across the web, often without warning of the graphic content that it contained. It seems that few sought Mir’s permission and almost all ignored the fact that he had chosen to remove the video, a clear signal that he no longer wanted it to be public.

There is also the question of safety to address. In the interview, Mir mentions that he was alone in his flat and spoke of feeling panicked. Much of the footage captured that day was taken from people inside the surrounding buildings. The gunmen were still at large and news reports were confused and frantic. It is hard to imagine how that must have felt.

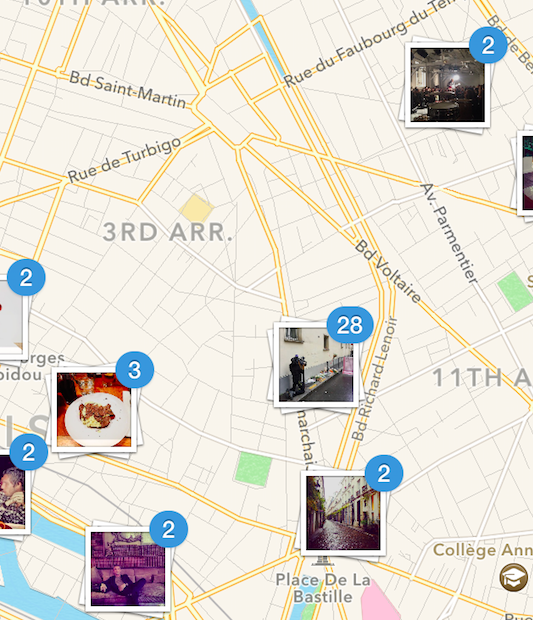

Instagram’s optional geo-location feature meant that many photos and videos were posted alongside the exact position of where they were taken. Did the news sites that chose to embed this content realise that they were also inadvertently publishing detailed information about where the eyewitnesses lived or worked?

Then there is consideration for the victim’s family. Much is made of how sites like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are ‘self-regulating’. We each have our own set of moral boundaries and if our judgement is a bit off then our online peers will soon let us know. After only fifteen minutes, Jordi Mir’s video had already taken on a life of its own, and he was no longer in control. It was up to the world’s media to handle the content as they would have done their own footage. But as we saw with some of the coverage of the Boston Marathon bombing, extremely graphic imagery that has already appeared on social media can be treated very differently. There is an assumption that ‘the public has seen it all already’.

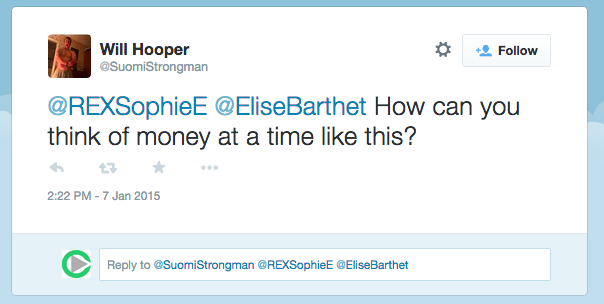

It is also worth reflecting on the expectations placed on these eyewitnesses, at a time when they are at their most vulnerable. Within minutes of posting a video or photo their comment and reply feeds are filled with permission requests and financial offers.

The homepage of Newsflare, one media agency that is often first to get in contact, states: “Shoot video, tell the world, get paid”.

But, dare to negotiate a fee for your footage and prepare to be reprimanded for seeking to profit from a tragedy.

Conversely, consent to your footage being used for free then find it locked behind a stream of adverts on a commercial news site. These requests are often mere courtesy, because if the content is publicly searchable then most news organisations will use it anyway.

So what more can be done to protect an eyewitness’s safety and their right to ownership and privacy? How can we ensure that their footage is handled responsibly and respectfully so that these incredible contributions to accurate, real time reporting continue?

Eyewitness Media Hub are planning to produce an advice guide for eyewitnesses so if you would like to contribute to this, based on firsthand experience, industry expertise or general observation then please do get in touch with jenni@emhub.co.