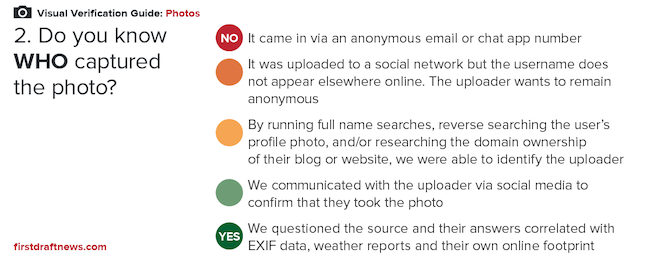

Verifying your sources is key to any online investigation. When you find some compelling footage or images, getting to the “who” of where they came from is essential, and First Draft’s Visual Verification Guides give a great overview of things to consider when getting to the source:

The ideal scenario, of course, is to be able to speak directly to a source, if possible and appropriate, on the phone or in person. Even then, mistakes can still happen, especially when a source is pretending to be something or someone they’re not. Often these people are just hoaxers, but there’s a growing trend of accounts acting as sockpuppets: fake online identities set up to push or derail certain political or social agendas.

Sources may not reply may not reply when you’re looking to talk to them, however. Maybe they’re busy, maybe they don’t want to talk to journalists. Another reason could be that your source isn’t a person at all: lots of accounts on social networks are bots.

Sockpuppets and bots pose some interesting challenges for verification, especially in parts of the world where governments are using them to manipulate social networks (and that’s more of the world than you’d expect) and knowing how to spot them can save time and pain.

Spotting a Bot

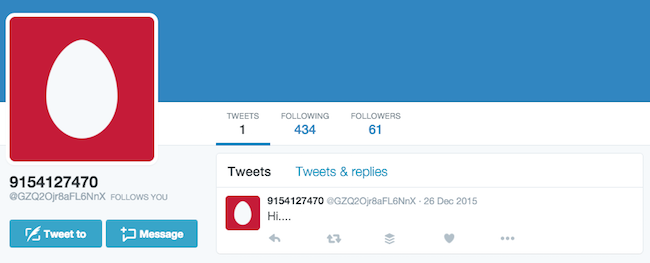

Uncovering a bot account can be trivially easy or deceptively difficult. Take these two Twitter accounts, for example:

Lots of red flags are instantly apparent about the first user here. The gibberish user name, the egg profile pic, the lone, brief tweet – this user will quickly fall foul of First Draft’s top tips for spotting hoax accounts.

The second account, whose latest tweet tells of a Pakistani prisoner who has escaped a Jeddah prison, however, is more of a challenge. Reasonable (if low) numbers of following and followers, a good sample of tweets, real-person profile pic, rational username and display names, posting a range of content (including photo and video) in a language we might expect. We need to do some more work

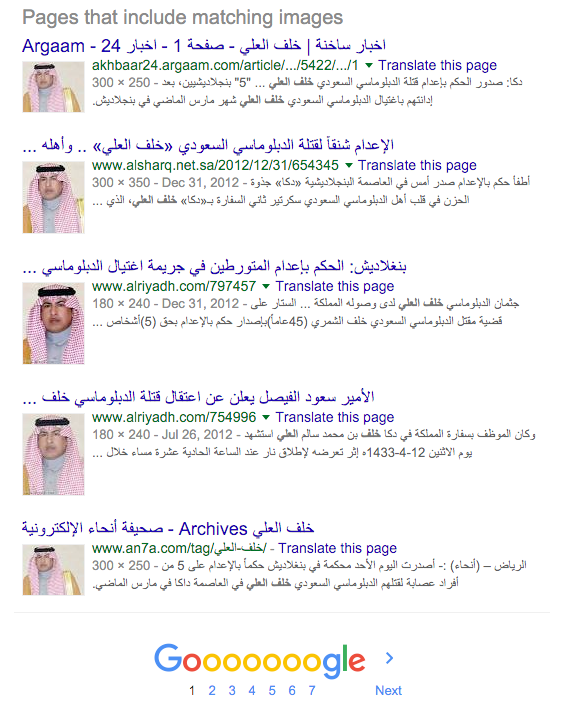

First, let’s check out that profile pic. Is it an original image? Fire up a reverse images search:

An immediate red flag is that it seems the profile photo is actually of a man named Khalaf Al-Ali, a Saudi diplomat killed in Bangladesh in 2012. So perhaps this user has posted his image in remembrance of the diplomat – let’s do more digging.

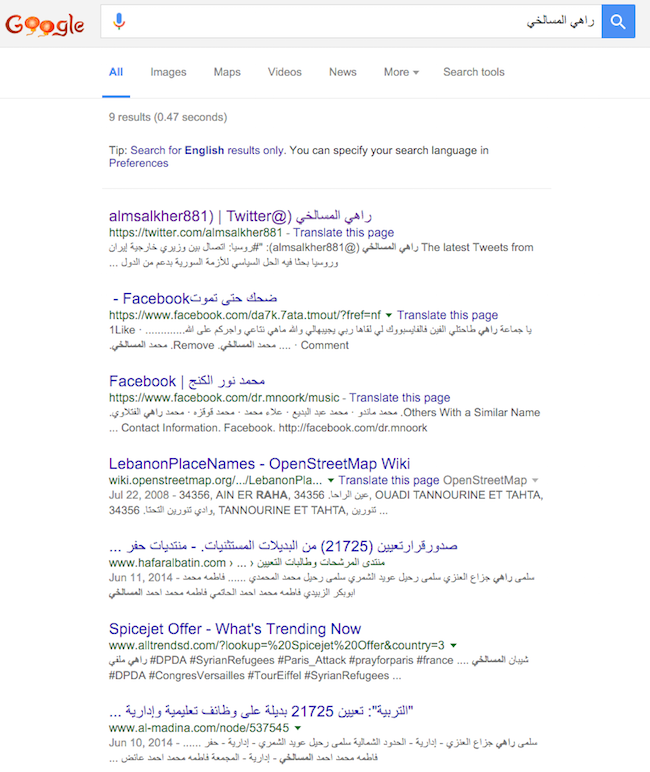

The second step is to see if we can find a real person named Rahi Al-Msalkhe, by Googling the Arabic display name.

No returns other than the Twitter account we’re investigating is another red flag. Maybe this person put a fake name on their account? Not that uncommon.

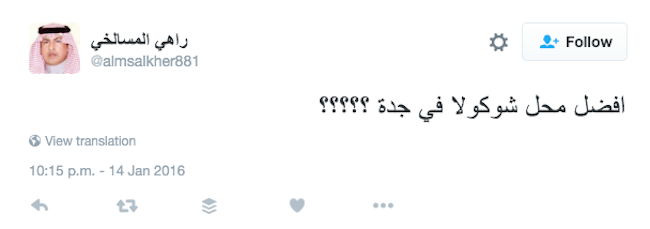

As a third step, let’s look more closely at the account’s tweets. They seem to be mostly Arabic-language sharing of links, with a couple of English tweets. Nothing too remarkable. From a brief search, this tweet seems the most personable and possibly gives a location:

Translation: What’s the best chocolate shop in Jeddah?????

“What’s the best chocolate shop in Jeddah?????” it reads.

A good question indeed, but it doesn’t seem like anyone responded. Let’s see if anyone else on Twitter asked the same question.

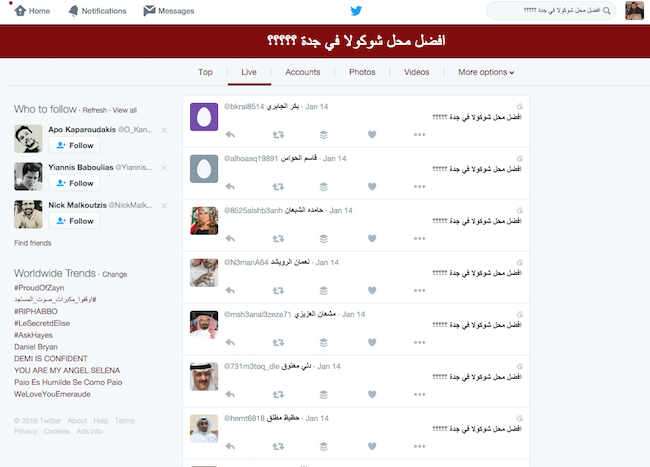

Oh dear! It seems that at 10:15 PM (US West Coast), January 14, around 100 accounts tweeted the exact same tweet.

It’s hard to imagine a scenario where this would happen in real life, and if we repeat the search on other tweets from @almsalkher881, we can find that this is a repeated pattern. At this point we can safely say the account is at best compromised, and very likely a bot. Clicking through any of the accounts that have tweeted duplicate content turns up similar results.

What purpose does the bot army serve? Without knowing who is behind it, it’s hard to tell. But some ways we’ve seen these bots and sockpuppet accounts used is to spam and smear activists, to shut down hashtags that criticize authority, and to spread disinformation.

Such efforts by states can be more elaborate than you might think. In 2015, New York Times reporter Adrian Chen published a fascinating in-depth view of a Russian “troll factory” – an office apparently dedicated to spreading pro-Putin news and opinions on social media.

Chen traces some highly complex disinformation campaigns back to the troll factory. In one example, officials and residents in a Louisiana town received text messages warning of an explosion at a chemical plant and the spread of toxic fumes. On Twitter, dozens of accounts started tweeting about the explosion, mentioning prominent journalists with screengrabs of CNN.com showing the “breaking” news. Videos emerged showing ISIS-like figures apparently claiming responsibility for the explosion.

There was quickly a Wikipedia page describing the explosion and linking to videos. All of this was faked, including fully functioning clones of local news websites carrying the story. This disinformation attack was followed by others, also playing on very real public fears such as #EbolaInAtlanta and #shockingmurderinatlanta.

While it’s unlikely that we’d encounter such well-coordinated disinformation campaigns on a daily or even regular basis, it’s extremely important that journalists are aware of the extent to which social newsgathering can be manipulated in these ways, and have a few tricks and tools up their sleeves to spot the bots.

A useful tool for spotting bots is BotOrNot, by the Truthy project. BotOrNot analyses a range of account features to give you a heuristic on whether the account looks like a bot, including network, user, ‘friends’, temporal, content and sentiment analysis.

BotOrNot isn’t perfect (it only returns a Bot score of 31 per cent for our chosen bot), but it can provide useful insights about accounts that we wouldn’t easily be able to access otherwise.

The social web is only just leaving its infancy, and the Internet on which it lives is only 20-years old in any real, publicly-accessible terms. Political actors will use whatever means available to spread their message, so it is vital that journalists are aware of the possibilities and how to identify them.

Check out “Sock puppets and spambots: How states manipulate social networks” and other reads and resources on verification.