It’s a difficult time to be working in breaking news. With the shift of focus to digital platforms and social media reporting, media outlets are pushed to be as fast as possible when releasing information in breaking news events. Alongside an increasing desire to be first with breaking news, there should also be an equally strong desire for accuracy, especially when lives and reputations are at risk.

Our basic journalistic instincts should tell us to err on the side of caution when releasing the names of suspects involved in harrowing cases, particularly when there are not enough sources to corroborate the information or sufficient amounts of investigation to confirm their involvement.

So why does the wrongful naming of innocent people in media reports continue to happen?

Take the case of Toby “Eggman” Reynolds, who was wrongly accused by users on the messaging board 4chan of carrying out a mass shooting at Oregon’s Umpqua Community College in October 2015. Storyful journalists Joe Galvin and Derek Bowler investigated this claim, eventually managing to talk directly to the man identified as Reynolds and confirm that he was, in fact, in Seattle, not the location of the shooting. By this time, however, some news outlets had released this rumour as fact, seemingly without undertaking any independent investigation.

In an older case, Sunil Tripathi, a student at Brown University, was wrongly accused of being a suspect in the April 2013 Boston marathon bombings. Reddit users and several reporters on social media speculated on the innocence of the 22-year-old, who had been missing for a month, and, in some cases, reporters said they had heard Tripathi’s name being mentioned on the Boston police scanner.

Tripathi’s body was later discovered in the Providence River, Rhode Island, on April 23, 2013. His body had reportedly been in the water for some time, and it was believed that he had taken his own life. While Tripathi may not have been alive around the time of the erroneous accusation, this example of poor ethics from reporters, who accepted and shared rumour as fact, had a devastating effect on his family.

“All of this was just noise, noise that just got louder because it kept bouncing off itself,” Tripathi’s sister Sangeeta said in an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It’s really crazy that someone sitting in their pajamas somewhere can start a chain that can get the media, traditional media that should have a certain amount of fact-checking, all really riled up.”

Storyful recently worked on a case of misidentification when a professor at Alexandria University was wrongly accused of being the hijacker of EgyptAir flight MS181. The flight was en route from Alexandria’s Burj al-Arab airport to Cairo on March 29, 2016, when it was hijacked and forced to land at Larnaca International Airport in Cyprus.

Reports from Egypt’s state news agency, MENA, initially named Dr. Ibrahim Samaha as the hijacker. Reports citing MENA said Samaha had been described as a man in his late 20s.

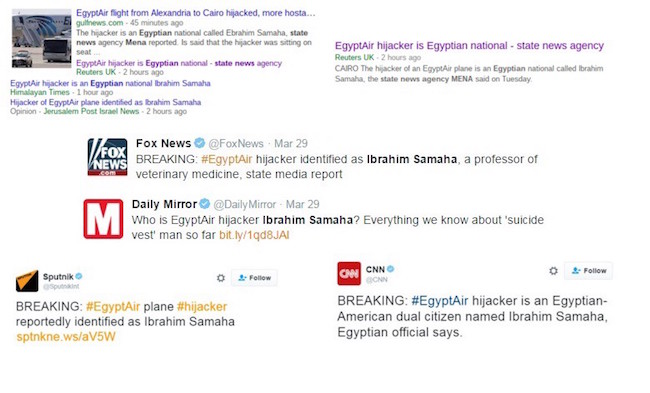

Screenshots of news outlets naming Ibrahim Samaha as the EgyptAir hijacker

At Storyful, we carried out some of our own research on this information to be absolutely sure we would be naming the right person, and to avoid misinforming our newsroom clients. In the first few minutes of the investigation, we found a number of discrepancies with the information gleaned from posts being shared around online.

Images were being widely circulated online, appearing to show the hijacker

While this was clearly not the original version of the photo, it was being widely shared as showing the hijacker of the flight, and did not appear to show a man in his late 20s. When our reverse Google Image searches came back without any results, we knew we needed to keep digging.

Further searches uncovered a page for Dr. Samaha on the Alexandria University website, which included a picture of the professor.

An image of Ibrahim Samaha posted to the Alexandria University website

This tallied with a Facebook account we found under the name of Ibrahim Samaha that also listed connections with the university.

Ibrahim Samaha’s Facebook account

Looking at this information, the picture circulating from the aircraft did not show a striking resemblance to the pictures we had found of Samaha. The reports of the hijacker’s age also did not add up with any of the content we had found.

Soon after, the BBC managed get in contact with Samaha, who confirmed that he was a passenger, but not the hijacker. The hijacker was later confirmed by Egyptian authorities to be 59-year-old Seif el Din Mustafa.

Once Samaha was released from the plane, he gave a few brief interviews. In footage from ONtv, Samaha said he believed the misunderstanding had derived from the cabin crew, due to a seating plan. Samaha also said his wife had called him while on the plane, asking him if he was the hijacker, before starting to cry. Further reports say Samaha’s wife, Nahla, did not want to talk to the press due to her “nervous shock and mental suffering.”

As the main role of news organizations is to accurately report information to the public, there should not be instances of innocent people being publicly named as suspects, particularly when there is enough easily discoverable evidence that produces more than one red flag. Nor should we be taking anything found on social media at face value, as getting the facts wrong can prove disastrous for those wrongfully accused (and embarrassing for the accusers). As the Reuters handbook has it: “Just because you have a named source does not mean you are free from responsibility for what you quote the source as saying.”

And as the cases of Reynolds, Tripathi and others similar show, when it comes to crowdsourced investigations on online platforms, nothing should go reported without thorough verification by professional journalists.

Is the trauma inflicted on people misidentified due to lack of verification work, and their families, really worth it in the race to be first?

Rachael Kennedy is a senior journalist at Storyful. Storyful’s Razan Ibraheem also contributed translations for this post.

Update: This article has been updated to show that Galvin and Bowler spoke “to the man identified as Reynolds” rather than “directly to Reynolds”. ‘Toby Reynolds’ was a pseudonym used by the individual, who later told Galvin and Bowler his real name.