In Brief

- WhatsApp played a prominent role in the spread of disinformation during Spain’s recent election, as it has in other countries.

- Spain’s far-right political party Vox and its supporters outmanoeuvred other political parties in Spain on social media. They were better coordinated across all platforms, including WhatsApp.

- Bots operated across the political spectrum, supporting all the major parties in Spain. The largest network of bots found by researchers originated in Venezuela and had nearly 3,000 Twitter accounts that spread messages supportive of Vox.

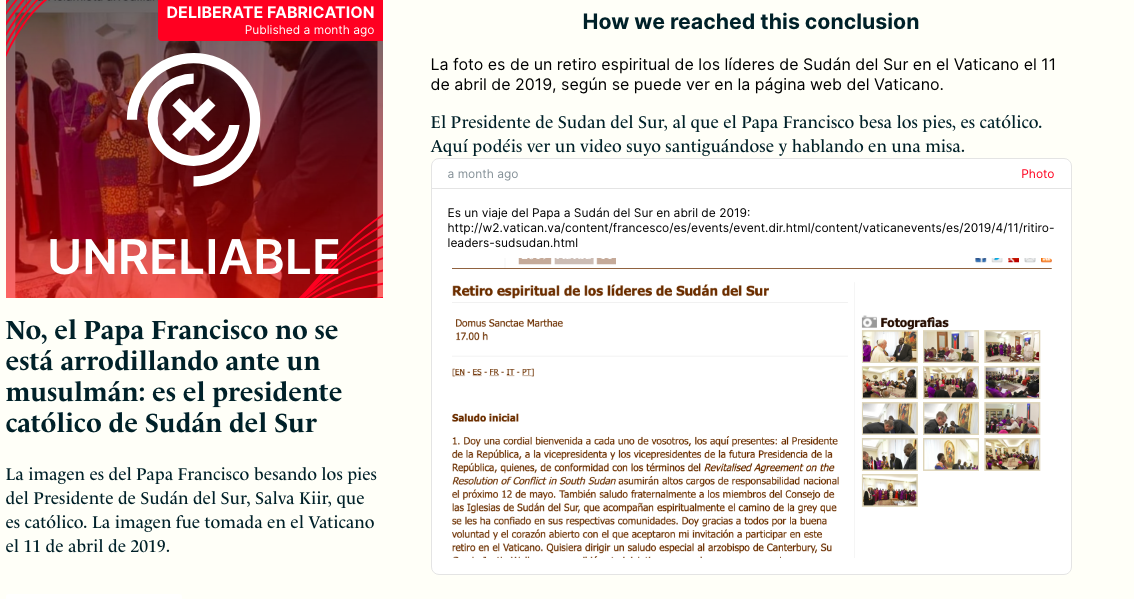

LONDON – “The Catholic Church surrenders to Islam,” the Facebook post reads. “We will never see a Muslim get on his knees before a Christian.” Below is a photo of Pope Francis kneeling before the president of South Sudan and kissing his feet.

The post appeared on several social media platforms in Spain in the lead up to the country’s recent snap election, amplified in part by Facebook groups supporting Spain’s far-right political party, Vox.

The claims behind the photo were eventually debunked by Spanish news and fact-checking organisations working collaboratively on CrossCheck’s Comprobado project– a collaborative effort between 16 newsrooms in Spain to shed light on disinformation, coordinated by First Draft and Spanish fact-checking organisation Maldita.es.

The photo is real. The Pope did kneel and kiss the feet of Salva Kiir, the head of South Sudan, during a spiritual retreat for leaders of South Sudan at the Vatican in April 2019. But Mr. Kiir, like the majority of South Sudanese, is a Christian, not a Muslim.

The photo was one example of the tide of misleading and false information targeting political parties and candidates during the recent Spanish election campaign. The April 28 snap election was called after Catalan nationalist politicians withdrew support for the Socialist government’s proposed budget.

With the European Union parliamentary elections taking place this week, the election in Spain offered insights into the kinds of disinformation that could be present during EU-wide vote, as well as the social media platforms where disinformation will likely concentrate.

WhatsAppening in Spain?

WhatsApp is quickly becoming the messaging platform of choice in many parts of the world. Given the popularity of the service in Europe, the Facebook-owned platform will likely be a significant conduit of information during the EU parliamentary elections.

The service has attracted many users keen on the privacy provided by the platform’s closed groups and end-to-end encryption. But users aren’t just turning to the platform for conversations between friends. The average use of WhatsApp for consuming news has almost tripled since 2014, according to the Digital News Report compiled by the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford.

Not all news on WhatsApp is good news, something that was highlighted in Brazil’s 2018 presidential election. That election campaign saw large amounts of disinformation – much of which was supportive of the current president Jair Bolsonaro – circulate through the platform.

“Much of the disinformation that circulated on WhatsApp then jumped on Twitter.”

For its part, WhatsApp has limited the size of groups and message forwarding as a way of curbing the spread of disinformation. But these measures had little impact in Spain, according to Laura Del Río, the fact-checking coordinator at Maldita.es, who says that WhatsApp was one of the most important platforms for diffusing disinformation during the Spanish election.

“In Spain [WhatsApp] has a big impact. We found many possible reports of disinformation through WhatsApp,” Del Río said.

During the Spanish election, disinformation would often begin on WhatsApp before spreading to other platforms.

“Much of the disinformation that circulated on WhatsApp then jumped on Twitter,” said Desiree Garcia, a journalist from EFE, Spain’s wire service, who is also part of Comprobado.

Similar to how Bolsonaro and his supporters used the messaging service to spread both genuine information as well as disinformation during Brazil’s presidential election, WhatsApp became a central tool of the social media strategy of Vox. Instances of disinformation and misinformation, alongside genuine and factual messaging, appeared in both official Vox groups as well as unofficial groups used by supporters during the Spanish election.

Vox pops on social media

Political parties and activists from all sides churned out volumes of information on social media during the Spanish election cycle. But no other party matched the energy and manoeuvring of Vox and its supporters.

The party not only utilized Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp to a large degree to disseminate their political messaging, but they also expanded their audiences on Instagram and YouTube beyond that of any other political party, with Instagram proving to be particularly useful for Vox in reaching younger demographics.

Other parties, such as Spain’s far-left party Podemos may have larger Twitter followings than Vox overall, but Vox supporters had far higher individual activity on the platform.

“[Vox’s] preferred mode of communication is social media which it knows how to exploit to its benefit and where it has found its own space away from traditional media and public scrutiny,” Cristina Monge, a political analyst and professor at the University of Zaragoza, told the BBC.

The strategy seems to have had success. The party has not only integrated vast numbers of supporters into its social media networks, but these same supporters have also done much of the party’s heavy lifting on social media, creating and spreading viral content, both genuine and misleading.

Other parties, such as Spain’s far-left party Podemos may have larger Twitter followings than Vox overall, but Vox supporters had far higher individual activity on the platform, according to Jordi Morales, an expert in network analysis. Per person, Vox supporters tweeted almost twice as much as people supporting the next closest party, underlining their motivation.

Venezuelan bot networks

Vox ended up winning 24 seats in Spain’s parliament, a huge leap for a party that sat on the margins of Spanish politics until recently, but still a long way from the 123 seats won by Spain’s ruling socialist party PSOE, which increased its majority in the snap election.

Vox’s successful social media strategy and motivated base of supporters likely played a role in the party’s gains. Some of this support came from outside the country.

An investigation by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) uncovered a bot network composed of nearly 3,000 Twitter accounts originating from Venezuela which spread hateful messages against Islam and in favour of Vox. The bot network was originally used to oppose the Venezuelan government, before being reactivated in 2017, according to the Spanish newspaper El País, who first reported on ISD’s findings.

The network published an average of 152,907 tweets a day in 2019 and mentioned Vox leader Santiago Abascal around 460,000 times. It spread numerous examples of disinformation, including a video of a riot in Algeria whose caption was changed to suggest the tumult took place in a Muslim neighbourhood in France. That video was promoted by one of Vox’s official accounts.

The Venezuelan network stood out given its size and origins, but bot networks, like disinformation, span the political spectrum. Over the last few years every big political party in Spain has benefited from bot networks, according to BotsdeTwitter, which tracks Twitter bots and suspicious Twitter accounts in Spain.

Disinformation continues

During the election campaign, the journalists and fact-checkers involved in Comprobado discovered various types of disinformation, including videos, memes and photos. The most common types of disinformation were false claims targeting Podemos, Vox, and PSOE – Spain’s far-left, far-right, and socialist party respectively

The content of these claims was vast, forcing journalists and fact-checkers to work across a range of subjects, including voter fraud, religion, LGBTQ rights, feminism, and racism. These claims were used primarily to debase political parties, candidates, and members of the media.

The Spanish election is now over but disinformation continues. Spanish journalists remain vigilant. Recently, a photo emerged on social media of Pablo Iglesias – the Secretary-General of Podemos – apparently hanging up posters of late Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez. The photo was shared by various groups on social media intent on showing the politician’s extreme left-wing tendencies.

The journalists and fact-checkers working on Comprobado quickly found the original image. It was taken in 2015 and showed Iglesias hanging posters of his party, not of Chavez. Like much of the disinformation flowing across social media, the image had been digitally altered.

Follow all the upcoming investigations in Comprobado on CrossCheck and on Twitter @ComprobadoEs.