As part of our work on building resilient societies in an age of information disorder, First Draft recently launched a series of ‘Standards Sessions’, regular off-the-record meet-ups that bring together journalists and academics in London, New York and Sydney to discuss urgent ethical challenges that newsrooms currently face. Reporters, editors and academics interested in attending our next Standards Session in September can register their interest using this form.

—

Joe Biden has had a bumpy start in his quest to be the Democratic Party nominee for the 2020 US election. A string of verbal slip-ups led to news coverage focusing on Biden’s propensity for gaffes rather than his favourable poll numbers.

The former vice president perplexed viewers during a recent televised debate when he encouraged them to “go to Joe 3 0 3 3 0”, an unregistered and unrelated domain name which now directs to satirical campaign site ‘Josh For America’. It later emerged Biden wanted people to text JOE to the number 30330.

To be fair, Biden is not the only person to blame for the confusion over his official campaign site. Less than three months ago, the most-visited Joe Biden website — and one of the top sites served up to potential voters in search engine results — was one full of mockery and innuendo, rather than a legitimate piece of digital campaigning.

“Uncle Joe is back and ready to take a hands-on approach to America’s problems!” exclaimed the welcome message. “Joe Biden has a good feel for the American people and knows exactly what they really want deep down.”

The home page detailed parts of his historical voting record, implicitly contrasting them with recent progressive positions, and looped videos of Biden touching women and children at press events — an allusion to his displays of overfamiliarity with women. (Biden has promised to be “more mindful and respectful of people’s personal space.”)

At the foot of the page, in lettering only slightly darker than the off-white background, read a disclaimer: “This site is political commentary and parody of Joe Biden’s Presidential campaign website.”

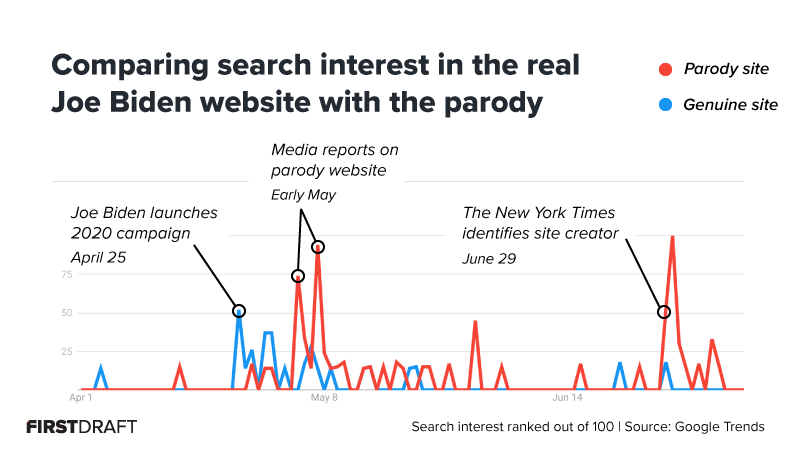

National and international news organisations spotted the self-proclaimed parody in early May and subsequent reporting only served to increase interest, pushing it ahead of the official Biden 2020 website in terms of searches in Google Trends results.

It was almost two months before the backstory behind the parody site was revealed. In a June 29 article, the New York Times’ Matthew Rosenberg identified its creator as Patrick Mauldin, who “makes videos and other digital content for President Trump’s re-election campaign” and runs a Republican consulting firm with his brother. Mauldin told the Times he made the site in his own time with his own money, not under direction from the Trump campaign.

Having pinpointed Mauldin as the owner of the site, Rosenberg stated that his article would not be linking to it.

“Links from established media websites are weighted heavily by search engines,” he explained in the piece. “The New York Times is not linking to Mr. Mauldin’s websites to avoid further boosting them in search rankings.”

But the day after his article ran, Google searches for the parody website went through the roof.

While there are no numbers showing exactly how many visitors were driven to search for the site because of the Times article, the timing of Rosenberg’s piece did coincide with a massive surge of interest. On June 30, the day after the Times story was published, Google search interest for the URL of the Biden parody hit its all-time high. Source: Google Trends

“Any time you write about misinformation and disinformation, the mere fact of casting a spotlight on it will amplify it a bit,” Rosenberg told First Draft in an interview. “There’s no way to avoid it.”

So what should newsrooms do, given that coverage of these websites can improve their search engine rankings and increase their visibility to the public?

At First Draft’s latest Standards Sessions events, journalists in London, New York and Sydney debated how newsrooms can best navigate the relationship between information disorder and search engine optimisation without falling prey to these types of manipulation efforts.

To link or not to link?

Linking out to sources is good practice for fostering transparency, yet this routine procedure becomes fraught in the context of covering disinformation, especially when the traffic generated from the link provides benefits to the site’s creator. After all, the Times revealed that Mauldin runs a Republican political consultancy and he sells t-shirts on his mockery of Biden’s campaigning site.

Participants in First Draft’s Standards Sessions in all three cities agreed that directly linking to the parody site runs the risk of amplification, but noted that hard figures showing the exact scale of the amplification would be helpful.

In its profile of Mauldin, the Times made the deliberate choice of not linking to the parody site as “I didn’t want to drive traffic to this site,” Rosenberg said. “That just seemed to defeat the entire purpose.”

Rather, Rosenberg chose to include screenshots of the site in the article, “for people who thought ‘I don’t want to go there and give this any kind of boost.'”

The Times also wrote out the URL in the second paragraph of his story, hoping that readers curious to see the site would just copy and paste the URL into the address bar rather than going to Google to search for it.

In a way, this tactic worked. According to web traffic reports from Alexa over June and July, the Times ranked third on the list of websites most frequently visited immediately before the parody. Newsweek, which ran two articles about the parody site in that period, was fourth.

Google was the first, with almost a quarter of all Biden parody visitors coming directly from the search giant, and Reddit, where a user claiming responsibility for the site had promoted their handiwork, came second.

At a glance, the parody (bottom) looks as slick and professional as the Biden’s genuine campaign site (top). First Draft.

Looking at this correlation, participants at First Draft’s Standards Sessions concurred that it was possible the Times’s choice resulted in an increased search interest in the site anyway.

Some journalists found the lack of linking problematic as a matter of transparency – if the site is significant enough to warrant its own article, shouldn’t the author give readers the chance to judge it for themselves?

Others found positives in the Times’s approach, pointing out that the article had done readers a service by clearly describing the relationship between links and search rankings, and by providing an explanation of why the Times denied amplification to the Biden site.

Several attendees noted that their newsrooms generally avoid using any links in their articles, regardless of the subject matter, since a link can be viewed as an endorsement.

‘No-follow’ links

Given the drawbacks in both linking to sites and not, ‘no-follow’ links provide another option for navigating such issues. Shortly after Rosenberg’s piece was published, several commentators on Twitter suggested that the Times could have used ‘no-follow’s. These included former Facebook Security Chief Alex Stamos and Aviv Ovadya, who wrote a tutorial on no-follow links for First Draft in 2016.

Here is a guide I wrote for journalists on how “nofollow” works, and what they should do to avoid boosting bad actors. I still regularly send it to journalists and they often actually fix the article—if you see something say something!https://t.co/7uA0WlrTZ2

— Aviv Ovadya ? (@metaviv) June 30, 2019

No-follow links are useful for newsrooms that wish to direct readers to a site, whilst also preventing the site from climbing up the search results.

These links can be easily created by adding rel=”nofollow” to a webpage’s HTML. In the published article, the no-follow link will look exactly the same as any other and take readers to the destination page. But behind the scenes, this attribute tells the search engines to ignore the link when evaluating the search ranking of the destination page.

Ovadya’s 2016 post goes over the no-follow process and repercussions in more detail.

Rosenberg said he and his editor did consider using no-follow links in the Times article, but ultimately decided against it because they believed the process was complicated to describe, taking up precious space and perhaps distracting the reader from the point of the story.

“The quickest and easiest way to explain this all was: don’t link. Put in a sentence [about the decision].” Rosenberg said.

Standards Sessions participants in all three cities were enthusiastic about no-follow links as a clean and relatively simple solution to the problem of amplification, although some pointed out that not all newsrooms’s content management systems allow for reporters and editors to go into the HTML and carry out the change.

Participants also noted that it would be helpful to have empirical data on the effectiveness of no-follow links – versus not linking at all – in stopping or slowing amplification. Rosenberg agrees: “There are no real hard numbers. We’re guessing a little bit here. They’re educated and informed guesses, but they’re not backed up by any hard data.”

Nevertheless, Rosenberg told First Draft he was open to considering the use of no-follow links for future stories.

“At some point, [the media is] going to have to start educating and getting readers comfortable with what the no-follow link is, and how to use it, and what we’re doing with it, and then explain it in a story that we’re using a no-follow link. But I also think we all need a better understanding of whether no-follow links are working or not.”

Framing the narrative

Beyond the issue of hyperlinks, First Draft’s Standards Sessions explored the question of whether the Biden parody website warranted a story at all.

While the creator’s desire for coverage and the site’s commercial element in selling t-shirts made some attendees uncomfortable about giving additional amplification, choosing not to report also felt like the wrong decision. Ignoring the site wasn’t an option for some journalists, who argued that even foreseeable but unfavourable consequences should not override the obligation to cover newsworthy stories.

Participants in favour of reporting agreed it was newsworthy because of the creator’s ties to President Trump and the Republican Party, but diverged on the most responsible way of framing the story.

The quickest and easiest angle would be to centre the article around the existence of the site itself, some participants said. But that approach may lead to a ‘whack-a-mole’ effect, setting a precedent of coverage for each and every fake site made by a political opponent.

According to the Times, Mauldin also built parody sites for at least three other candidates for the Democratic nomination. Should the press report on every single one of these sites, alerting readers to disinformation that might otherwise be ignored, and pushing each site further up the search results?

Attendees suggested several possible frameworks for such cases, including:

- Centring the article around the person or organisation that produced the disinformation, and their motivations for doing so (as the Times chose to do).

- Situating the parody site as just one of multiple examples of successful SEO gaming, and then folding the examples into a longer trend piece that focuses on the search engines’ vulnerability to rankings manipulation.

- Writing a cautionary tale about the candidate who failed to register all potential website URLs for his campaign.

- Turning this into a “teaching moment” and warning readers to be wary of sites that may look legitimate but have suspect domain names.

For his part, Rosenberg said it would be a “fool’s errand” for any one journalist to try and keep up with each suspicious website or instance of disinformation that appears.

“I’m much more interested in the system that produces it, that pumps it out to us,” he said. “And that’s why my interests lay much more with the guy behind the site than the site itself.”

His decision to make Mauldin the focal point of the article also serves to break stereotypes around where such cases come from, as “it is important to convey to readers that [the creators of disinformation are not] just outsiders, or people on the fringes. This is becoming a mainstream phenomenon,” he added.

As disinformation campaigns and media manipulation attempts proliferate, journalists must be aware that any story published about disinformation has the potential to direct traffic and increase reader interest.

Newsrooms must make challenging decisions every day about how to best report such stories, balancing newsworthiness against the consequences of amplification.

—

First Draft thanks all of our Standards Sessions participants, and our rapporteurs Jekaterina Drozdovica, Laura Garcia, Diara Townes, Ariam Alula, Meg Kanofski, Jessica Xu, Eleanor Harrison-Dengate, Danielle Hynes and Kate Rafferty.

If you’d like to share your thoughts about disinformation, amplification and SEO, please email us at ethics@firstdraftnews.com.

Journalists interested in attending our next Standards Session in London, New York or Sydney can fill out this form to be considered for invitation. Spaces are limited at each session and we seek diverse contributions from a range of backgrounds and experience.