There are now more active social media accounts than there are people in the world. The number of mobile devices has outnumbered global population for over a year now. And as mobile technology and internet accessibility spreads further around the world, these numbers are only going to increase.

Social media is the digital town square where the human race now meet, converse and find information. There are politicians begging for trust and votes on their soapboxes; there are merchants pitching and selling from their stalls; demagogues, iconoclasts and soothsayers preaching to the multitudes. And there are normal people talking about their lives.

The self-proclaimed purpose of journalists and news organisations is to be the best source of information and truth for their readers, guiding their audience through an online crowd that gets bigger and noisier by the day.

“So much time, so many resources, conferences and handbooks are focussed on engagement policy for social media, how to tweet the right thing from a brand account,” said Fergus Bell, co-founder of the Online News Association’s UGC Ethics Initiative, at a recent news:rewired event.

“You can undo all that in an instant.”

While audience development teams and social media editors focus on engaging their readers in published material, a large part of the modern newsroom is now focussed on finding stories and sources on social media, among the crowd in the digital square.

But there is a public backlash against this newsgathering process, in more ways than one.

“User-generated content [UGC], ethics, the best practice for UGC and the way we are working in social newsgathering, for me, is all about sustainability,” said Bell. “How do we keep this content coming to us in the future? We need it and we need it more. More and more content is produced everyday.

“We have to do it right or we’re going to turn off our audience. It’s really important to the future of the industry.”

‘This photo could not be independently verified…’

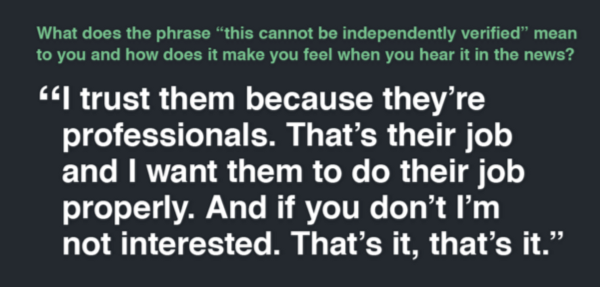

From Eyewitness Media Hub’s research into audience attitudes to news organisations using eyewitness media

It has become common in the news industry to see disclaimers attached to pictures or videos found on social media when they have not been verified fully.

These kind of disclaimers aren’t good enough though, said Bell, especially when audiences know how and where to find the same information themselves.

Trust was a huge factor among focus groups when in recent research from Eyewitness Media Hub into audience attitudes to online news and verification practices, and one group in particular summed up the problem:

Chris: It screams of, like, zero quality control if you just put anything on the TV and go ‘There you go, that might be true’.

Dawn: Yeah, exactly.

Lindsey: Anyone can do that.

Dawn: I see them as professionals and I want them to do a job, and if they’re not delivering, then I’m not interested.

As Bell put it: “What is the value of a disclaimer, except to hide behind?”

Building a clear workflow around newsgathering and online verification is the first step, and understanding the steps and tools necessary in verification. Then it’s simply a matter of being honest with audiences about the process.

“We should start thinking about [saying] ‘this photo/video/information has been verified based on…’,” Bell gave as an example. “Talking about our processes.

“Transparency is key here and that comes back to sustainability. Our audience are going out looking for this, they know where to find it, they are on their computers at work, on their iPad in front of the TV.

“They are finding this stuff. They have verification skills of their own and they need to know that we can do the same.”

‘Omg there’s someone shooting on campus’

When Chris Harper-Mercer began shooting students and staff at the Umpqua Community College in Oregon on October 1st, tweets from eyewitnesses were vital in getting the news out.

One user in particular received a disproportionate amount of attention from journalists all over the world because of the urgency and terror of her posts.

Screenshot of tweets from an eyewitness to the UCC shooting. The tweets have been reordered to red chronologically from top to bottom and the username redacted

Reporters everywhere started contacting the user: “DM me when you find shelter”, “are you actually at UCC? Hope all is well”, “I’m a reporter, are you able to talk?”, “Can we contact you to find out what’s happening?”, on and on and on.

Mixed in with the reporters were other Twitter users wishing the eyewitness well, and many, many more reacting with anger and disgust to the journalists approaches.

“You should be fired for this. will be contacting your employer”; “you are a vulture”; “you are the lowest form of human garbage”; “it’s unbelievable all these reporters just unbelievable”.

“People haven’t necessarily done anything wrong [here],” said Bell, “there just isn’t a better way yet.”

The UCC shooting is just another recent example in a long list of many where reporters need to get close to the story but, in doing so, can end up driving sources away.

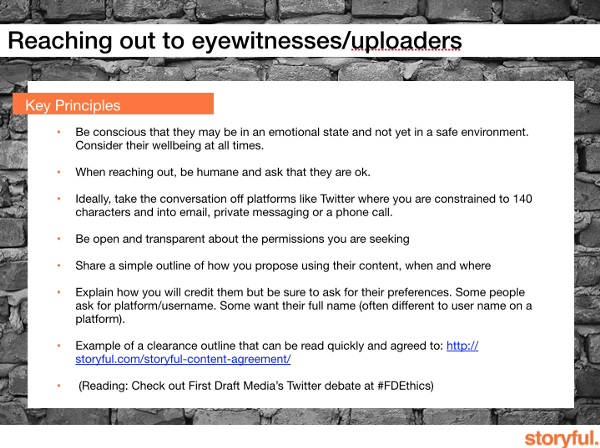

Aine Kerr, managing editor at Storyful, said news organisations need to consider their responsibilities when working with eyewitnesses and eyewitness media.

“What is your responsibility to that eyewitness, to that uploader, in that moment?” she said.

Many of these eyewitnesses “are in vulnerable situations, dangerous scenarios”, she said, they have never dealt with the media before and are once-in-a-lifetime witnesses to an extraordinary event.

Running up to them and shouting at them to get in contact — in the middle of the town square, without knowing if they are safe, with everybody watching — is only having a negative effect. That’s not to say there are any instant fixes at present, but there are bad practices which drive audiences away.

Guidelines for reaching out to eyewitnesses on social media. Aine Kerr/Storyful

Around the Oregon shooting, there were even cases of multiple reporters from one outlet contacting the same user on the same tweet. At the Associated Press, however, producers waited to hear from police that the shooter was no longer active before reaching out.

AP producers take “a sensitive and thoughtful approach when using social networks to pursue information or UGC from people in dangerous situations,” said Beth Colson, AP’s head of news production, international video, “or from those who have suffered a significant personal loss.”

“We don’t want to put them in danger. We need to think before we contact them to remind them about their safety. It’s got to be more than ‘stay safe’.”

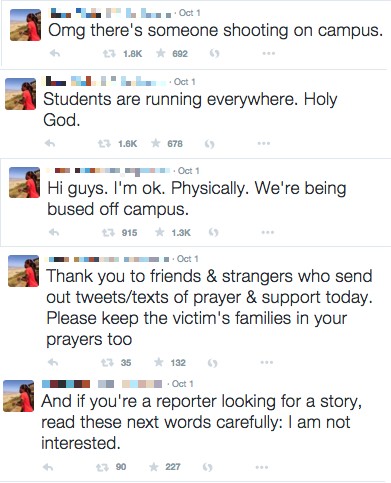

In the case of the UCC shooting, many people on Twitter were urging witnesses to ignore reporters, to be safe and find shelter. The response?

Screenshot of tweets from an eyewitness to the UCC shooting. The tweets have been reordered to red chronologically from top to bottom and username has been redacted

The eyewitness thanked “friends and strangers” for their support and essentially told reporters to get lost.

“What possible incentive would she have to talk to reporters?” said Bell. “There was little co-ordination between reporters, producers and desk staff, multiple requests are public, they look insensitive and, frankly, it’s amateurish.”

For all the people who interacted around the eyewitness tweets in Oregon, and the hundreds more who saw the conversation but did not take part, the likelihood of them wanting to be a source and help reporters if they are involved in future would have dropped significantly.

All the hard work that goes into audience engagement can be undone by reporters simply doing their job, following the same guidelines as they have been taught. So news organisations need to come together to find a solution, said Bell, before online sources are turned off from helping journalists forever.

“There are certain standards that we can come to and there are certain standards that we’ve already come to outside of digital news. Just because this is new doesn’t mean we can’t get together and talk about it.”

‘Video via YouTube’

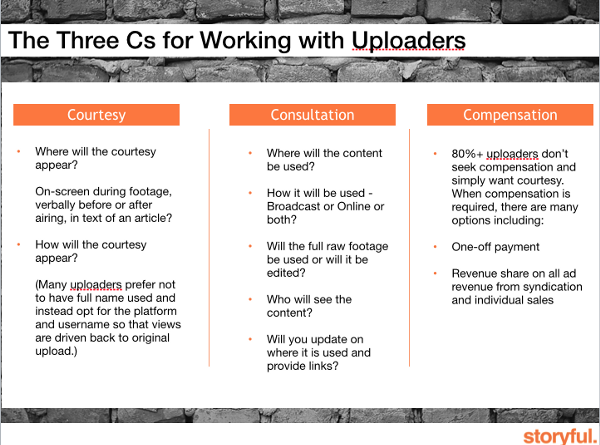

That issue of giving sources an incentive is central in persuading them to co-operate, said Kerr, in giving them something in return for helping with a story.

Most of the time this comes down to crediting, but every user is different in how they want to be credited. While some want their full name, others may want their username, while more may not want to be credited at all.

Three ways Storyful works with uploaders, and the incentives for co-operation. Image courtesy Aine Kerr/ Storyful

“Uploaders, even though they’re often in one-off eyewitness scenarios, they’re savvy and all on Twitter and Facebook and Vine and Vimeo,” said Kerr.

“They know how to track their content. Uploaders we’re dealing wth everyday are setting up Google alerts around keywords, around their names and usernames, to see who’s using it and everyday we are inundated with uploaders coming to us and saying ‘Did that person have permission? Did they come through you?’”

After gunmen opened fire in the offices of Charlie Hebdo magazine in January, one man captured footage of the an attacker executing a fallen police officer. AP interviewed him about what he went through.

“The most personal thing, he said, was not only that he regretted what he did but that all the world’s media were broadcasting his video but nobody had asked him anything,” said Colson. “That tells us a lot about the way we are working currently. We need to make sure whoever created that content understands what we’re doing with it.”

More research from EMHub was identified the myriad different ways that online sources are credited: from usernames to embeds and scrapes marked “video from YouTube”. But crediting a social platform as the source is as good as crediting “telephone”.

“If we don’t do this right then people are just going to turn off,” said Bell. “They’re our audience and we’re going to lose their respect. They can see that we’re not acting right.”

“Your body doesn’t know that you’re not in Syria”

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

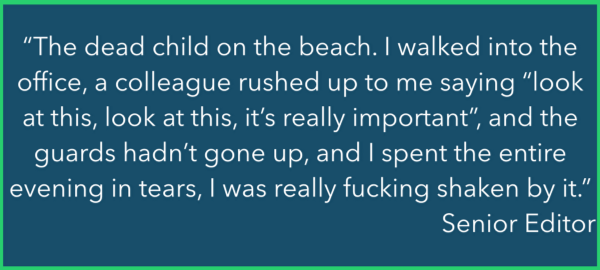

While much of the focus around best practice and ethics in using eyewitness media revolves around sources, the effects on journalists are just as important when it comes to questions of sustainability.

“The body’s defence mechanisms evolved millions of years before social media,” said the Dart Center’s Gavin Rees. “So if we’re watching very rich, high-definition footage coming into the brain in large quantities, particularly with very realistic sound, your body doesn’t know that you’re not in Syria, standing next to the person who’s just been executed.”

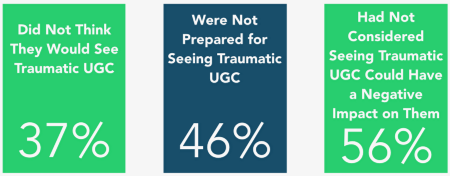

Sam Dubberley of Eyewitness Media Hub recently wrote about the organisations first findings of research into vicarious trauma, and found that while progress is being made in understanding and catering for the effects of viewing traumatic images, there is still a long way to go.

The two biggest factors in causing vicarious trauma among journalists viewing graphic images from social media are the ‘surprise’ factor and the amount of exposure.

Just like physically bracing for impact, the shock of seeing traumatic images when the brain has not been steeled to resist can deal more damage. The body’s defense mechanisms react before the brain can process what it is seeing.

And if this happens regularly over time, the effects are even more serious. Police are at just as much risk from vicarious trauma as journalists, and the American Psychiatric Association recently updated their guidelines on post-traumatic stress disorder to understand the problem better.

“Trauma is a bit like toxic radiation,” continued Rees. “Just like nuclear workers, at times we have to go into the reactor and expose ourselves to the material. But we have to think of it as a dose relationship. So anything we can do to soften the trauma is going to be very helpful in reducing our exposure.”

Understanding this relationship better can go a long way in reducing the negative impact but the first step is in recognising that traumatic imagery is distressing, and distress is not a sign of weakness or permanent damage.

Many respondents to an Eyewitness Media Hub survey were not fully prepared for what they might see in their work. Image courtesy: Sam Dubberley/ Eyewitness Media Hub

“When we expose ourselves to traumatic imagery, one of the impacts of distress is that it hampers our cognitive ability to process information,” said Rees, “and you might have felt that in the newsroom when traumatic stuff is coming in, thinking can become tunnelled and focussed and the unspoken distress in the air can also affect how we collaborate with each other.”

“People have different ways of coping and part of it is building up what works for you, building your own resilience and finding out what works for you in terms of resilience,” Dubberley said.

This may mean turning a video’s sound off or taking regular screen breaks, said Rees. Getting in contact with nature and talking about the imagery helps as well. It may even be as simple as putting a piece of paper or post-it note over the traumatic parts of an image if the focus is elsewhere, like identifying a building in the background.

And for individuals, establishing a personal plan to cope is vital.

“Check in with yourself,” he said. “If you’re doing immersive trauma work you need a self care plan. You need to think what are you going to do in the course of your work to remove extra pressure.”

Bad management practices are “the worst” offenders, as they can violate an understanding of fairness and social balance that is already well-stretched by traumatic images.

“Some simple workflow steps can be taken in newsrooms to solve this problem,” said Dubberley, some of which can be a better scheduling process to rotate people on social media desks during particularly troubling stories.

Most of all, though, management should be aware of what their staff are going through, he said, be conscious of the effects traumatic images can have, and help them make sure they are working to the best of their ability.

“We all know the amount of UGC we handle is only going to increase,” said Colson. “We’re only going to have more of it. We’ve got a duty of care to the creators of the content as well as our own staff searching for it, away from the actual events.

“If you spend all day looking at graphic video and are only a click away from seeing something disturbing it will impact you. You can’t ‘unsee’ things…”

If these issues aren’t addressed they will continue to erode the relationship between news organisations, audiences and journalists, to the detriment of all.

“There are ways to be competitive and ethical at the same time,” said Bell. “No policies that we could possibly devise around this would work if they’re not competitive as well as ethical. And I think that it requires the industry to work together.”

Fergus Bell, Aine Kerr, Beth Colson, Sam Dubberley and Gavin Rees were speaking at a news:rewired event in London, organised by Journalism.co.uk

Alastair Reid is managing editor of First Draft News and, full disclosure, was previously editor of Journalism.co.uk