One of the quickest ways to find images and sources around a breaking news event is to use geolocation tools.

Yomapic, Echosec, Gramfeed, SAM Desk, Geofeedia and others all use data from social networks to let users find posts by location — most of the time it’s as simple as drawing a ring around the area of interest and setting a time period. The tools look for metadata which match the search criteria and — bingo — relevant posts are returned.

Reported.ly uses hundreds of publicly available Twitter lists for regions to find breaking stories around the world and geolocation tools are the next step in digging for more.

“But just because you’re getting information with geolocation data doesn’t mean you’ve actually got the right information,” said Andy Carvin, editor-in-chief at Reported.ly, at a recent Tech Raking event in Boston.

A glaring example came from Yemen at the start of September. Locked in a civil war since March, many Yemeni cities have been bombarded by Saudi airstrikes trying to crush the rebellion and restore the former government.

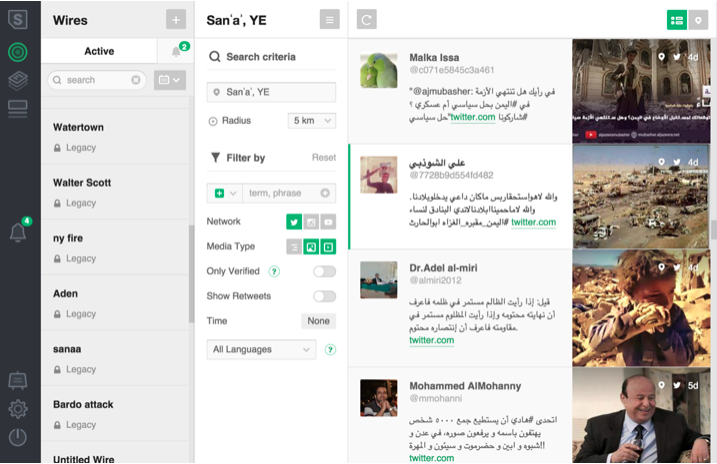

Searching for information on SAM Desk, Carvin spotted an image which seemed out of place.

Screenshot of SAM Desk, searching for news from Yemen across social networks. Andy Carvin/Reported.ly

“The second photo down [in the screengrab above] shows what appears to be a catastrophic attack in which many cars and buildings were damaged,” he said.

“The picture… came from a Twitter user complaining ‘Why do we have to rely on other countries come fight our battles, we may as well give our guns to our women.”

The user’s misogyny aside, the photo was geotagged as coming from Yemen at a time of ongoing Saudi airstrikes and the tweet was shared widely.

Screenshot of the tweet which shared the image, geotagged to Yemen

A quick reverse image search confirmed the image was not of Yemen at all, but from the infamous ‘Highway of Death’ in the first Gulf War, almost 25 years ago.

So how did this happen?

Carvin put it down to the “WhatsApp effect”. The private messaging app is quickly closing in on a billion users and in areas like Yemen many communities share information privately around big events with their friends and family.

“It ends up in this process by which someone takes the photo that they want to share, maliciously or maybe in pure ignorance… and circulates it through their friends on WhatsApp or any of the other [private messaging apps].

“Then someone in that network thinks ‘oh this is a great photo so I’m going to remove it form the closed network and upload it to a public network like Twitter’.”

If that user has geotagging enabled on their phone, the image’s metadata will trick geolocation tools into thinking the photo was taken at a completely different time and place from where it originated.

“Once that photo gets uploaded you’ve got Yemen tagged at the bottom and it becomes a case of what you might call ‘footage laundering’,” he said, “in which the tools of these closed networks change the metadata in a way that, if you’re not very, very careful, you’ll think it’s a different incident.”

And if geolocation is automated in the newsgathering process this can land journalists and news organisations in trouble very quickly.

In the first days of the Saudi campaign in Yemen a major international broadcaster played a looping montage of “dramatic images geotagged fo Sana’a”, said Carvin, showing the effects of the airstrikes.

“My followers immediately recognised these photos as ones they’d seen the year before in Gaza.

“So even news organisations that are familiar with these techniques of geolocation will sometimes fall for [footage laundering] because they haven’t recognised the implications of how closed networks have become the more common tool for sharing photos, rather than the open networks first.”

If platforms like Twitter can alert journalists to incidents then geolocation tools are the best next step for going deeper, but it is not foolproof. And although reverse image search can certainly make a difference here, no single method can prove or disprove a piece of content by itself.

Check out the First Draft visual verification guide for photos and videos for other ways to verify material from social media.