Bringing communities into the news process is a powerful way to spread journalistic values, train residents on reporting processes and foster user generated content that is more useful for newsrooms. Newsrooms are well positioned to become participatory journalism laboratories, helping more people navigate, verify and create powerful stories online and via social media.

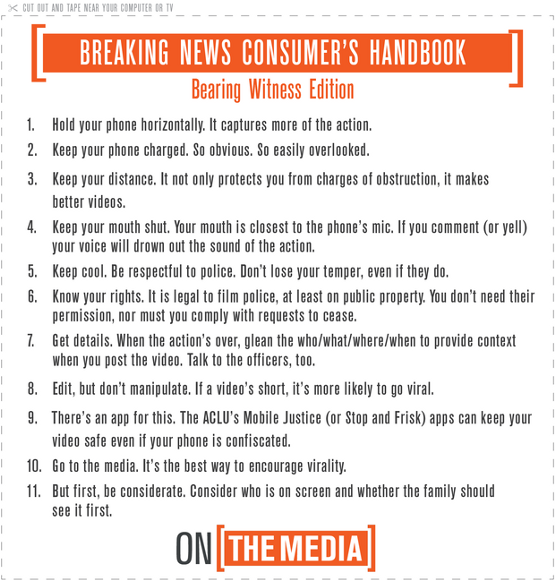

Last month after a teen in McKinney, Texas, captured eyewitness video of a police officer pulling a gun on black teens and and pinning a young woman to the ground, On The Media produced the “Breaking News Consumer Handbook: Bearing Witness Edition.” The handbook consisted of a simple image with 11 bullet points on it outlining important legal, safety, ethical and technological advice for people who find themselves recording police activity and breaking news. It does a superb job breaking down these complex issues into something that is approachable and relevant to most people.

Via OnTheMedia.org

The “Bearing Witness Edition” was actually On The Media’s fifth Breaking News Handbook. In the fall of 2013 when they introduced their first edition On The Media wrote that they were tired of telling the media how to do better reporting during breaking news, and instead were turning their attention to the audience instead. “Rather than counting on news outlets to get it right, we’re looking at the other end,” they wrote. “Below are some tips for how, in the wake of a big, tragic story, you can sort good information from bad.”

Lead by example

On The Media’s Breaking News Handbook is just one example of how newsrooms can empower their communities to better assess accuracy and validity of information during breaking news. A number of newsrooms are making public debunking a part of their work. See for example Gizmodo’s Factually and the Washington Post’s regular coverage of “What Was Fake on The Internet This Week.”

In this case, these newsrooms are leading by example and helping cultivate more skepticism in their readers. At their best, these posts don’t just point out fake photos and rumors but also explain how the authors were able to debunk them — what tools they used, what they looked for, the questions they asked.

It is not enough to simply report accurately, today we need newsrooms to also help debunk misinformation, especially during breaking news. And we should enlist our communities in that effort.

During breaking news we turn to our communities, to social media, to piece together what is happening, to find sources and collect images and photos from the ground. We rely on them in those moments. As such, we should do everything we can to help people understand how best to help create and share more trustworthy information.

It is not enough to simply report accurately, today we need newsrooms to also help debunk misinformation, especially during breaking news. And we should enlist our communities in that effort.

Why engage readers?

There are a range of benefits to engaging our communities and especially training our readers and our residents to be active participants and eyewitnesses:

- We help them to help us, by creating videos, photos and even tweets and tips that are more useful to newsrooms and speak to the kinds of details we need to verify reports on the ground

- They are more likely to debunk misinformation and help slow the spread of rumors by not RTing or sharing bad information

- They will be more aware of their own rights to gather and disseminate the news and will stand up for those rights

- They will report safely and consider journalistic ethics

- It can help streamline permission and licensing questions

- It makes the work of journalism more transparent, accountable and valuable

Not to mention a range of other benefits that can come from deeply engaging your community.

This should be a service we provide to our readers, but through collaborations with libraries, schools, local nonprofits we can reach even more people. MOOC’s like the one on news literacy being offered by ASU are also potential tools we can tap into. Some newsrooms, like WHYY and Making Contact are investing in terrific community journalism trainings, and organizations like Media Mobilizing Project, Press Pass TV and the Citizens Campaign have a long track record in equipping and empowering communities through media.

We need to make sure that verification and news literacy are part of those efforts too. (The truth is that many newsrooms and journalism schools need more access to trainings around verification and eyewitness media — which is one of the goals of the First Draft Coalition.)

My experience working at the intersection of journalism and communities is that people are hungry for tools and strategies to better identify trustworthy news and information and how to sort through the flood of info they face, especially around crisis, disasters and controversial issues in their communities.

Increasingly the probability of truth

In 2013, at an event on “truth and trust” organized by the Poynter Institute, Clay Shirky argued that people are looking to adopt journalistic skills and skepticism because given the flood of information they are navigating, they have no other choice. At one time, audience trust came largely through scarcity.

The abundance of news and information is cultivating a more sophisticated audience that wants to not only understand the news but also the process behind the news. “The man with one newspaper knows what the news is, the man with two is never sure,” Shirky joked. Shirky said that we should think about news today the way we think about the weather, with a probability attached to it.

At the 2013 event mentioned above, Tom Rosenstiel of the American Press Institute pointed out that while a diversity of sources can help us verify and get at the truth, it is also true that amidst a flood of information knowledge is harder to create because we have to sift through more details.

Closing the gap between those two is often the work of journalism during breaking news. As Dan Gilmor notes in the introduction to his news literacy MOOC mentioned above, “We’re in an age of information overload, and too much of what we watch, hear and read is mistaken, deceitful or even dangerous. Yet you and I can take control and make media serve us — all of us — by being active consumers and participants.” That is the good news, we are all in this together.

When it comes to breaking news — and the future of journalism more generally — we are all in this together.

In crisis moments, when the facts are a matter of life and death, we should be glad to have more boots on the ground, and we should lead by example and when engage our communities to help us shine a spotlight on the truth.