A journalist is only as good as their sources. Trainees get this phrase drummed into them from early in their careers, and very often these sources will be a member of the public who has a particular insight or experience relevant to a story. They may be a nurse, a police officer, a government insider, a community leader, a local council officer, an eyewitnesses to a breaking news event.

Cultivating and developing these sources takes time and skill, creating a relationship of trust and openness between the two parties to the point where the source is willing to give the journalist information they otherwise would not. The difference between a good story and a great scoop often lies in the sources.

So why, when working through social media, should online sources be treated any differently?

“A post, a video, is only a piece of information on a platform until you actually do journalism,” said Aine Kerr, Storyful’s managing editor, at a news:rewired event in London last week.

“We talk about traditional journalism, but is there a difference? No. What you still have to do at this point, with all the technological resources you have, is still apply the who, what, where, when, how and why.”

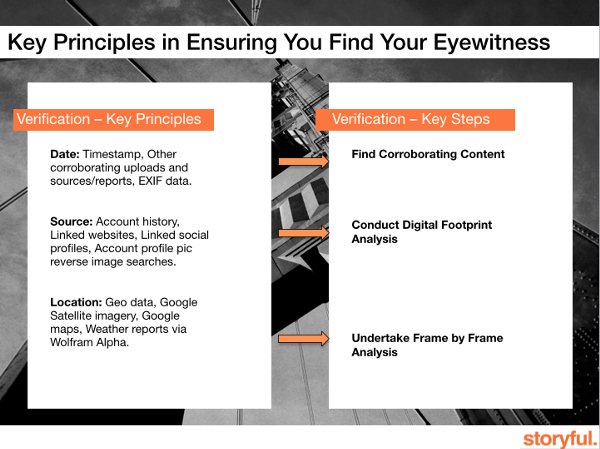

Verifying the date, location and source of a picture, post or video should be the very first step in understanding whether it is useful for a story, but to really get the inside track on what is happening “you’re going to have to rely on those eyewitnesses on the ground”.

“You still have to apply true journalism, good journalism, to reach out and have the conversation with your source,” Kerr said, and that takes the same interpersonal skills and empathy in the online world as it does in real life.

Image courtesy Aine Kerr/Storyful

“The key to our approach is to verify what you’re looking at, make sure you know what you’ve got, and make sure you’re sure you’re talking to the right person,” agreed Beth Colson, head of news production for international video at the Associated Press.

“We take into account the situation the eyewitness is in and make sure, when we talk to them, that they understand what we are asking of them. Did they take the video? Were they there? Is it theirs to give us? But we have to make a concerted effort to think about the way we contact people to secure this content. We need to acknowledge that we have a duty of care to the creator.

“If someone has just seen something that we consider to be a key moment in a story, chances are they’ve seen something traumatic that they didn’t expect to see.”

The current rush to get the quotes, get permissions and get the story ahead of the competition is resulting in a very public stampede of reporters on social media, behaving in a way they never would in person, with the end result of driving potential sources away.

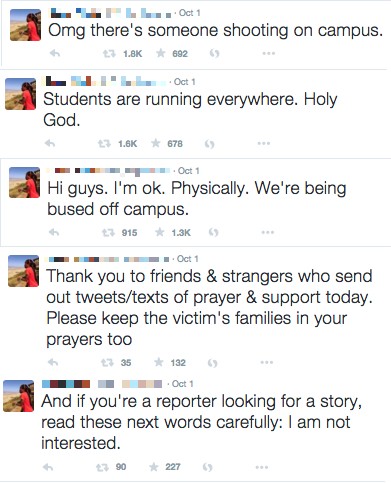

Some witnesses to the recent shooting at the Umpqua Community College in Oregon posted on Twitter what they had seen, and were faced with a barrage of requests for contact.

Screenshots of tweets from reporters hoping to contact a witness to the UCC Shooting. Usernames have been redacted

To the reporters and editors, they are reaching out to the witness of a breaking news event with huge public interest. But the witness is probably confused, terrified for her life

A reporter would never stop a witness fleeing a mass shooting to ask a few questions. Neither would they stick a dictaphone in the face of someone hiding under a table to “get their story”.

The hundreds of responses to these approaches from members of the public were almost entirely negative and, unsurprisingly, the witness did not reply to any of the requests.

Screenshot of the witnesses tweets, rearranged to read chronologically from top to bottom

Establishing proper workflows in the newsroom can help here, and AP take a “sensitive and thoughtful approach when using social networks to pursue information or UGC from people in dangerous situations or from those who have suffered a significant personal loss,” said Colson, and a real concern for safety beyond simply saying “stay safe”.

So in Oregon, AP producers waited to hear from the police that the gunman was no longer active before potentially contacting sources.

“One thing we’re not very good at doing as journalists and editors is we never ask ourselves what is the incentive for this person to help me?,” said Kerr.

“You’ve seen the bombardment that journalists are guilty of, but why are [witnesses] incentivised to help?”

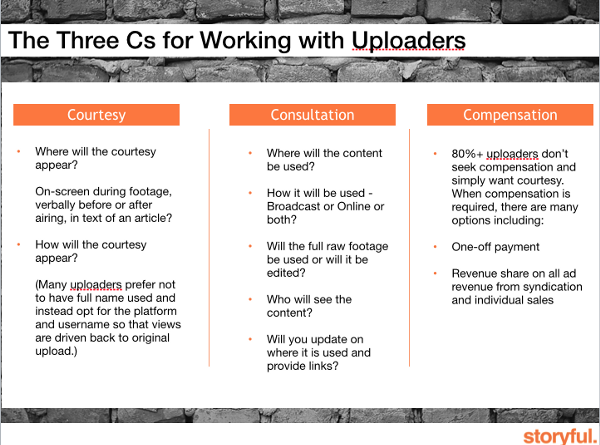

The “vast majority” of online sources just want to be credited, said Kerr, while only “10 to 15 per cent” want some form of compensation “if you enter into [the story] in a spirit of working with them on it.”

Image courtesy Aine Kerr/Storyful

Again, this is not all that different from years past. The ubiquity of camera phones and social media means the value of amateur footage has gone down, and it is often only the truly rare or unique and newsworthy footage that commands a fee.

As for quotes or footage, would reporters pay sources or witnesses in the past? Largely, no. Sending a tweet takes only marginally more effort than saying the words themselves. But every source would want to be credited properly, and many news organisations still fall short of this practice.

“Some people don’t want to have their first or second name out there for very good reasons,” said Kerr. “More often than not they will want you to put the platform and their username because they want you to get followers or more likes on Facebook, the views on YouTube. Have that conversation about how they would like to be credited.”

The value here is in building a relationship with the sources and the audience in the same way reporters would before the internet. People would want to be credited in their local paper and show their friends, making the experience positive for that person and their community.

“That is invaluable,” said Kerr, “that they can actually go and share it, show friends how they did some thing in the public interest.

“What we’re talking about is news stories and when you get into this conversation with an uploader to say ‘look, my work on this story is in the public interest, it’s important to our audience’.

“And then coming back to them to reward them for having trusted you, to say ‘here’s how you contributed to this story, that was really important storytelling’.”

Most users know how to track their own posts and know their rights, said Kerr, and many contact Storyful for legal advice to manage the situation.

Ignoring sources’ rights around online content and not speaking to them not only means news organisations could be “headed for incredibly serious legal difficulties” but also ignoring the opportunity to get closer to the story.

“When you think back to your sources down the years it was a relationship of trust and openness and transparency and fairness,” said Kerr, “It is no different now to treat uploaders in the same way.”

Aine Kerr and Beth Colson were speaking at a news:rewired event in London, organised by Journalism.co.uk

Alastair Reid is managing editor of First Draft News and, full disclosure, was previously editor of Journalism.co.uk