The world’s biggest Covid-19 vaccination drive is underway in India, with the ambitious goal of vaccinating 300 million people by July. This has been met with a wave of vaccine hesitancy as doubts around Covaxin — approved by New Delhi in January along with the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, known in India as Covishield — continue to spread.

Covaxin was developed locally by Indian vaccine maker Bharat Biotech. Although information around Phase 1 trials was published in The Lancet, Phase 3 trials are still underway.

The lack of published data around Covaxin’s development in some ways mirrors AstraZeneca’s failure at first to publicly disclose a dosing error that saw higher efficacy rates among participants who received a half first dose, sowing public doubt about the vaccine.

In the case of India, the lack of data around Covaxin coincides with a slow start to the country’s vaccination drive. The first phase of the immunization program, aimed at healthcare and essential workers, has seen some states register a turnout as low as 22 per cent in early January. Vaccination rates currently linger around 56 per cent nationally, well behind expectations, according to the Economic Times. India scaled up its vaccination program March 1 and jabs are now available to those over 60, or younger people with other illnesses.

While India does not historically have a large or vocal anti-vaccine movement, the rollout of a jab with limited data has contributed to doubts around India’s overall vaccination program.

Emerging skepticism

Several prominent Indians, including former cabinet minister and Congress Party politician Shashi Tharoor, journalist Rajdeep Sardesai and lawyer and activist Prashant Bhushan, expressed doubts about the vaccine on social media following its Jan. 3 authorization for emergency use in India.

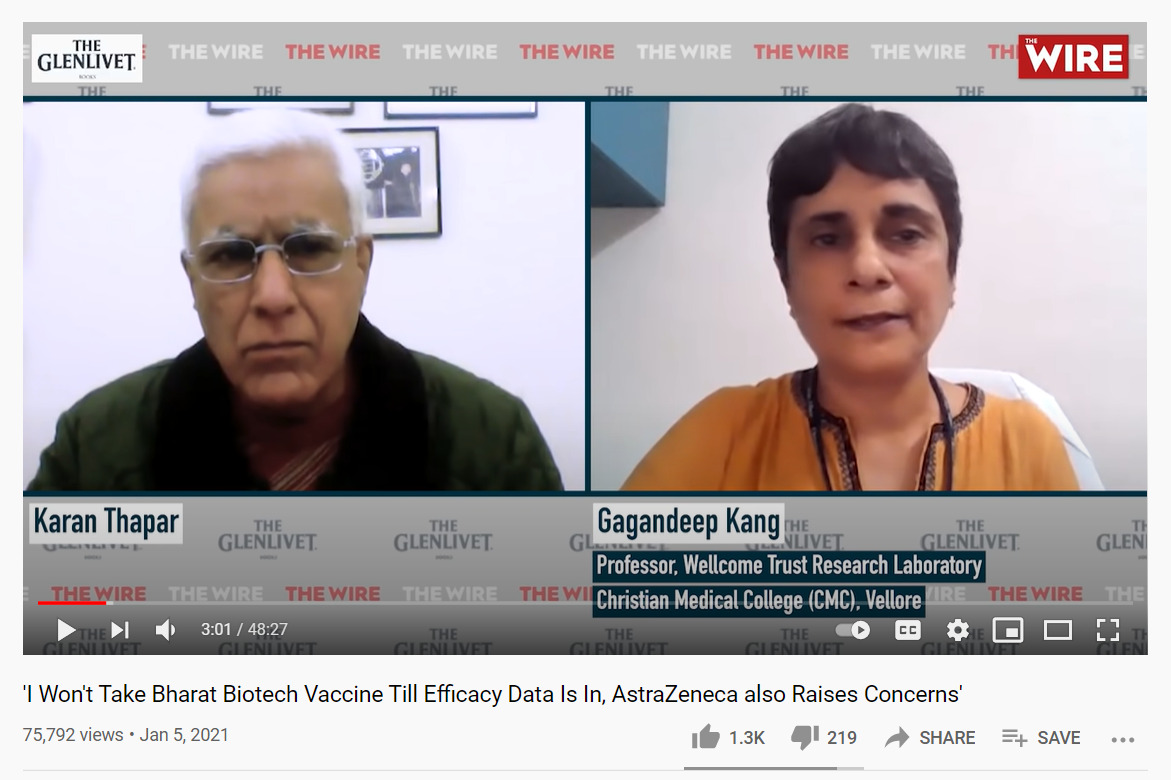

On January 6, Professor Gagandeep Kang, the first female Indian scientist to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, asked why the government had approved a vaccine without efficacy data in an interview with India’s The Wire. Kang also expressed concerns with Covishield, noting that the dosing error — which raised concerns among scientists around the world — during trials was “messy.” Further media interviews, including one in the influential The Hindu, led to the hashtag #GagandeepKang trending on Twitter, and a January spike in Google searches for “Gagandeep Kang” and “Gagandeep Kang vaccine.”

Dr. Gagandeep Kang said she wouldn’t take Covaxin until it’s efficacy data was made public in an interview with The Wire

In mid-January, several media outlets, including the Times of India, reported that people would not be allowed to choose which vaccine they would receive. Doctors, scientists and activists raised fears about the distribution of the homegrown Covaxin, given the lack of efficacy data, and their views soon spread widely on social media.

Soon after, Indian activist Sakhet Gokhale, a prominent critic of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, filed a complaint in court against the country’s drug regulatory body, asking for information around the safety and efficacy of the jab. Gokhale also repeatedly tweeted about the lack of information about Covaxin around this time.

Doubts among a growing number of doctors also soon gained significant national attention. In mid-January, a report of doctors in a New Delhi hospital refusing the Covaxin jab and requesting AstraZeneca’s Covishield was shared by several national news outlets, including NDTV, The Caravan and India Today.

Another group of resident doctors from the southern state of Karnataka raised concerns about the lack of choice in vaccines, writing a letter to local health authorities. National media outlets, including The Times of India, The New Indian Express and ANI, covered the story.

For its part, Bharat Biotech has come under fire over how it recruited Covaxin study participants. An investigation by NDTV in January revealed that the biotech firm was testing the jab on victims of the 1984 gas tragedy in Bhopal, reportedly misleading “over a dozen people” to sign up with payments of Rs. 750 (around $10). According to Scroll.in, 700 out of 1,700 participants were victims of the Bhopal chemical disaster, and participants were not given copies of the mandatory consent forms.

The death of one study participant sparked further debate online. Bharat Biotech said the death was unrelated to the vaccine, but social media users claimed that the “Bhopal gas victims [were] being hoodwinked into #Covaxin clinical trials” and that they were “guinea pigs.” News of the participant’s death also led four NGOs that support the survivors of the Bhopal disaster to write to Modi to ask for a halt to vaccine trials in the city.

The government’s approach

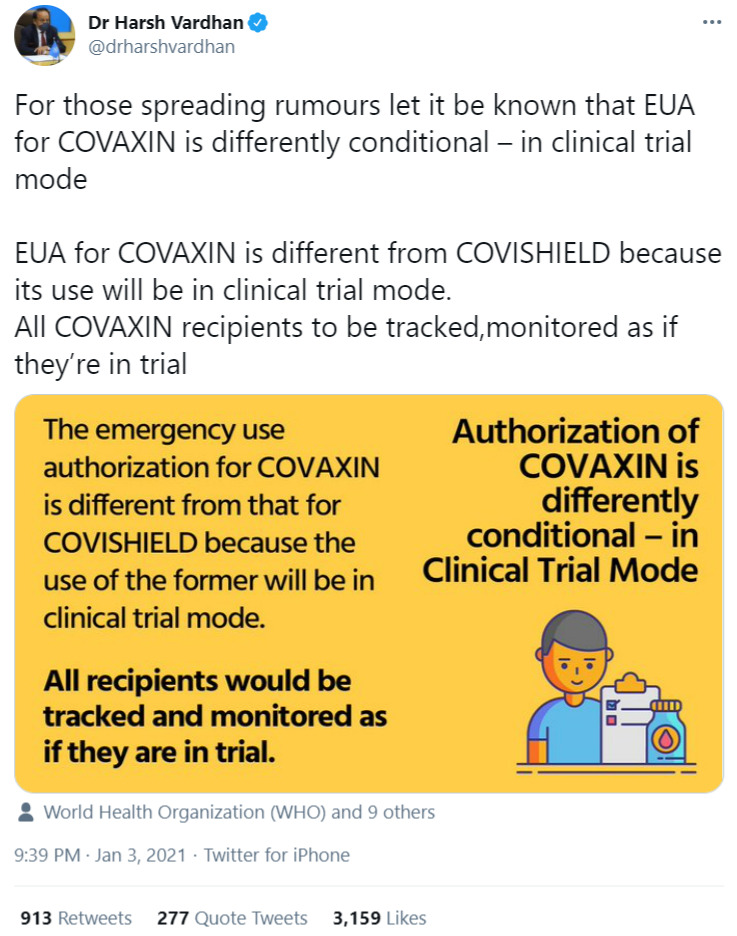

Initially, leading Indian officials acknowledged that Covaxin had no reliable efficacy data but would be rolled out anyway given the severity of the pandemic. Following Covaxin’s emergency authorization, Indian Health Minister Harsh Vardhan tweeted that it was granted approval in “clinical trial mode,” with an accompanying image that said “all recipients would be tracked and monitored as if they were part of the trial.”

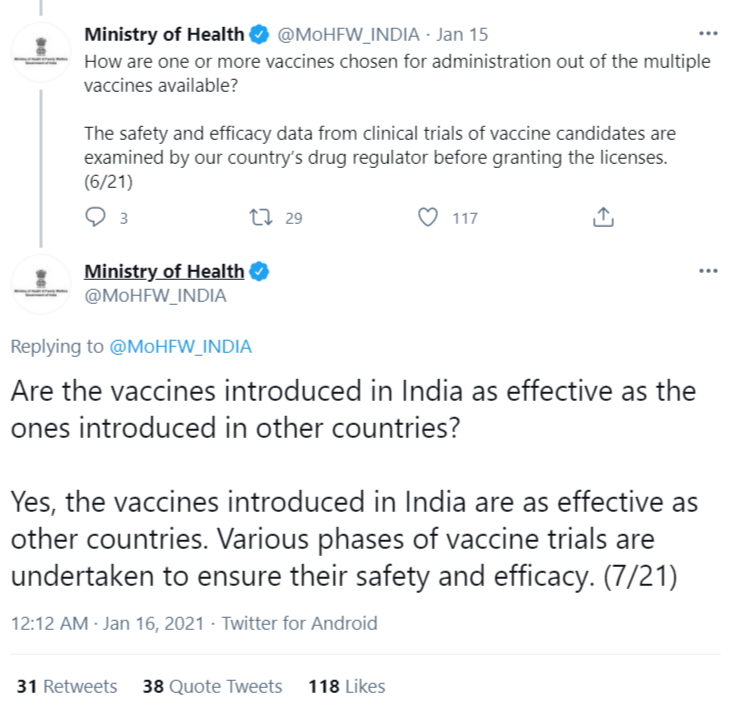

But in mid-January, the official handle of India’s health ministry changed course and claimed in a tweet thread without providing evidence that “the vaccines introduced in India are as effective as other countries.” Users called this a lie, saying: “Immunogenicity data does not equate [to] efficacy data.” (Immunogenicity is a measure of immune responses, while efficacy data measures how well the vaccine works in reducing the disease’s worst symptoms.) Some asked if any other country has licensed a jab without Phase 3 trial data.

- The health minister’s initial tweet saying Covaxin was granted approval in “clinical trial mode”

- The health ministry’s later tweet saying the vaccines being used in India were as effective as those abroad, despite the lack of Phase 3 trial data for Covaxin

On January 21, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the body tasked with the country’s rollout of vaccines, misleadingly cited a report in The Lancet about Covaxin’s Phase 1 trial to claim “remarkable results.” Several accounts replied to ICMR’s tweet, saying that “the ‘phase-1’ trial term is missing in the main tweet” and that it is “absolutely dangerous to give it to public without disclaimers about Phase II and Phase III trials.”

Recent developments

Last month, the opposition-led Chhattisgarh became India’s first state to reject Covaxin, asking for the vaccine’s distribution to be halted until its efficacy and safety were proven. The state’s health minister tweeted an image of the letter he had sent to the federal health minister, stating his “inhibitions regrading [sic] the incomplete 3rd phase trials of COVAXIN.” Although India’s health minister responded and said fears about Covaxin were unfounded, Chhatisgarh’s government continues to refuse the use of the jab.

Yesterday’s news of Prime Minister Narendra Modi taking his first dose of Covaxin appears to have raised some confidence in the jab online, as hundreds of users claimed that the PM taking the jab “quells all fears and removes all doubts” around Covaxin and that it “eliminate[s] any hesitancy or doubt among public towards #MadeInIndia vaccine.

India continues to scale up its vaccination program as Covid-19 cases rise in the country. Covaxin may eventually prove to be an effective and safe vaccine. But a lack of public confidence in the jab, despite government backing, could have wider consequences when it comes to vaccine hesitancy in India — including vaccines that have published Phase 3 trial data.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.