Celebrities used to be singers, actors and athletes we got to know through a little black box called television. The free and limitless access of social media has since stripped away the distance between celebrities and fans, allowing social interaction at the touch of a button. With visually appealing content and carefully crafted captions, celebrities can attract a massive global following eager to know their every next move and thought, whether they are established household names using new platforms to speak to fans (Madonna with her 15.6 million followers on Instagram) or budding superstars who shot to viral fame (Charli d’Amelio, a 16-year-old TikTok influencer who recently became the platform’s first creator to hit 100 million followers).

However, celebrities and influencers must be aware of their responsibility when it comes to how quickly they can share misinformation to their millions of fans. The damage can be exacerbated by media reports that repeat the misleading or false claims for clicks. Regardless of whether they spread misinformation intentionally or not, celebrities are complicit in information disorder.

This year has shown the role celebrities can play in amplifying misinformation. In January, singer Rihanna, who has close to 100 million followers, shared a misleading image of the Australian bushfires on Twitter. In April, actor Woody Harrelson shared the “negative effects of 5G” with his two million Instagram followers. And in July, rapper Kanye West told Forbes that he believed a coronavirus vaccine could “put chips inside of us.” West has more than four million followers on Instagram. The additional challenge is that oxygen can create more oxygen — a celebrity tweeting a rumor or falsehood can become a news story in itself, causing even more people to be exposed, as we saw when Harrelson and other celebrities’ posts about 5G tipped a fringe conspiracy theory into the mainstream. The groundless rumors about 5G resulted in real-world harm, with phone masts being burned to the ground in the UK.

This isn’t just a Western phenomenon. In India, Bollywood movie star Amitabh Bachchan has acquired a reputation for spreading false and misleading information online, such as claims that applauding could “destroy virus potency” and that homeopathy could “counter corona.” Both tweets were shared by hundreds of Bachchan’s 44.8 million followers. Meanwhile, in Australia, celebrity chef Pete Evans has promoted a plethora of conspiracy theories to his millions of followers, such as the “potential health risks” of 5G (similar false claims about 5G have also been shared across the world, such as in the UK and the Philippines) and an artist’s “map” that purportedly demonstrates the connections among various QAnon conspiracy theories. Multiple media outlets, including 7News and Daily Mail, repeated those baseless claims in their headlines, inadvertently reinforcing them. Only after Evans posted an image with a neo-Nazi symbol in November did he start to face repercussions, with brands and publishers banishing him.

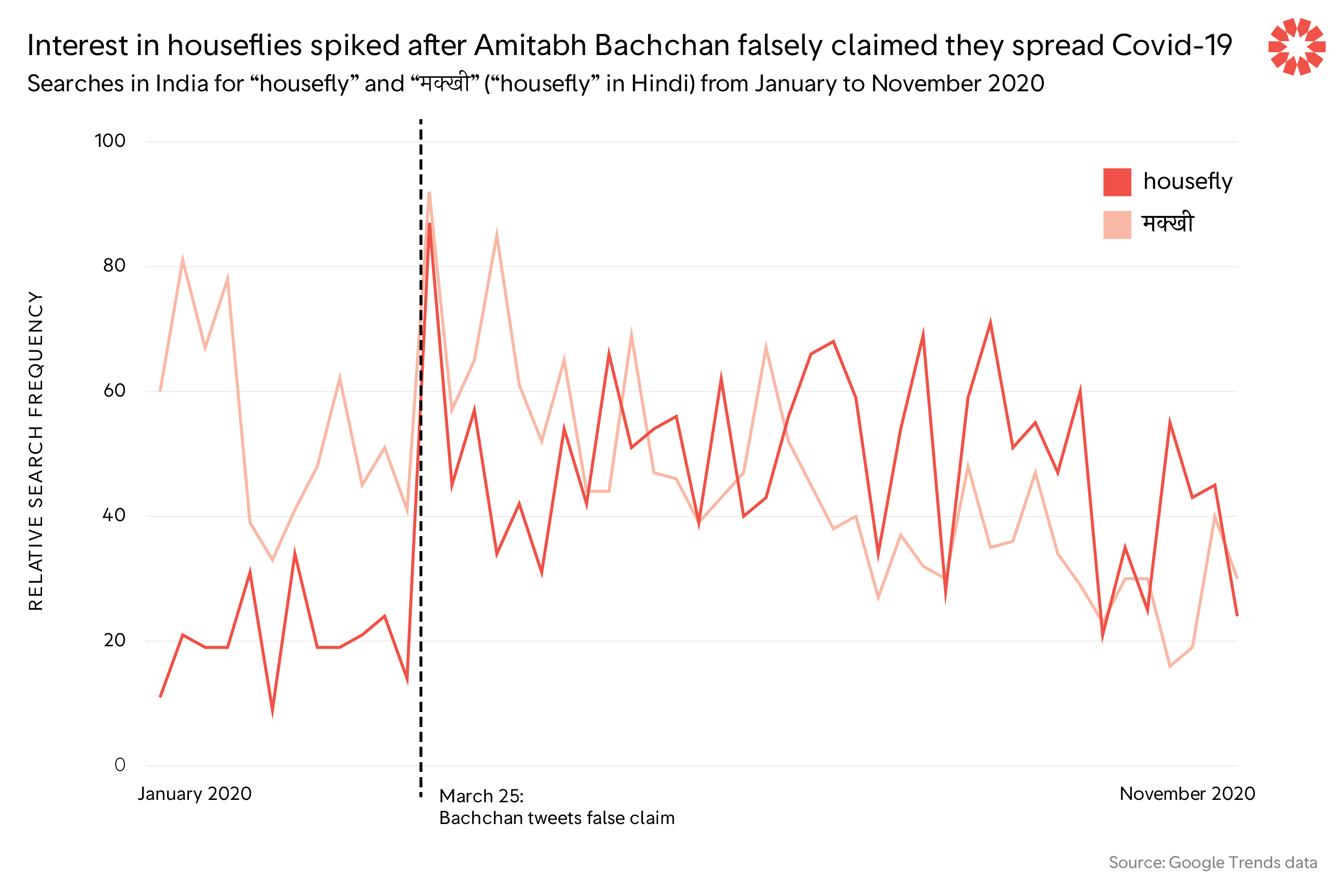

Fans’ strong emotional connection to their idols and heroes means they are often predisposed to believe them and trust their messages. This trust disarms fans in the face of mis- and disinformation spread by the celebrities and influencers they follow, nudging them to research and possibly repeat false narratives. For example, Amitabh Bachchan’s tweet from March falsely claiming that houseflies spread the coronavirus was followed by a spike in searches for “housefly” and “मक्खी” (housefly in Hindi) in India, according to Google Trends data.

Google Trends data reflects a rise in searches for the words “housefly” and “मक्खी” in India shortly after actor Amitabh Bachchan falsely claimed houseflies can spread the coronavirus. (Graphic by Ali Abbas Ahmadi)

Kate Starbird, a professor at the University of Washington, goes a step further in her analysis, where she says fans engage in “participatory disinformation” because they are “inspired” by influencers to voluntarily create and expand similar, false narratives and conspiracy theories.

The role of emotion is often overlooked in media literacy campaigns even though it is a strong driver of shares on social media, and therefore a powerful force in disinformation campaigns. Being aware of one’s emotions and how they can be manipulated, as outlined in First Draft’s “psychology of misinformation” series, is one way fans can be better inoculated against misinformation.

The imbalance of power between celebrities and influencers and their fans is further accentuated by social media companies’ sometimes confusing and often inconsistent policies related to misinformation. According to both Facebook and Twitter, a verified badge is granted to accounts that are notable and authentic, but there appear to be no consequences when authentic, verified accounts share lies and half-truths. In addition, politicians are exempted from Facebook’s Third-Party Fact-Checking Program, so any political misinformation they share usually remains online.

2020 has also seen the continued rise of “celebrity journalists,” i.e., news anchors and commentators who have built sizeable followings because they tend to sensationalize their reporting and do not appear to be bound by traditional journalistic principles of balanced, fair and factual reporting. For instance, Indian news anchor Arnab Goswami has acquired a reputation for sensationalist reporting and for promoting hateful information and conspiracy theories — such as falsely accusing members of a Muslim missionary group of spreading Covid-19. In Australia, commentators such as Sky News’ Peta Credlin and Alan Jones are often misconstrued as journalists, with their views mistaken for facts. Similarly, in Hong Kong, commentators such as Lee Yee and Chip Tsao, along with members of the pro-democracy camp, have voiced support for US President Donald Trump over his hardline approach to the Chinese Communist Party. Opinion pieces from them are considered a representation of their publishers’ stance.

Celebrities and online personalities enjoy an outsized influence on social media, but 2020 has shown they are a disproportionately important vector in the disinformation ecosystem. The size of their direct audience on the platforms, combined with the recognition their online activities receive from the mainstream media, can make them dangerous players when they share false or misleading information. In 2021, let’s avoid giving oxygen to inaccurate and false information and be mindful about the amount of airtime given to influencers and celebrities, especially those who are repeat offenders.