Ever since disinformation became a worldwide moral panic in 2016, one word has been thrown around with alarming regularity: bots.

Headlines often conjure up images of shady Russian hackers marshalling an army of automatons, ready to pounce on trending topics, to promote a particular narrative, or set societies against one another.

But bots take on many guises and appearances. They also tackle many different tasks. And it’s this diversity which makes detecting automation difficult, frustrating attempts by some of the world’s top researchers, academics and machine-learning algorithms.

“Even in the actual [field of] bot detection a lot of academics have different metrics for how they define what an automated account is,” said Samantha Bradshaw, a researcher on Oxford University’s Computational Propaganda Project. “It’s all very confusing and very messy.”

So, let’s get some definitions out of the way. In phraseology perhaps more fitting for a sci-fi fantasy blockbuster, automation expert Stefano Cresci talks in terms of bots, trolls and cyborgs. Bots are fully-automated accounts running purely on code, whereas trolls are accounts run by people who often hide their real identity and motives to stir up discord or division. And cyborgs?

“[They] are hybrid accounts that feature some level of automation but also there’s the intervention of humans,” explained Cresci, a researcher at the Institute of Informatics and Telematics at the Italian National Research Council in Pisa. Where bots are pretty cheap to run, cyborgs and troll accounts “require much more effort and I think much more money because you have to pay humans for operating the accounts.”

The delineation should be simple but, as the technology and strategy behind automated and co-ordinated information campaigns has evolved, it has become harder to tell the difference between the three.

Bots, cyborgs and trolls, oh my

These days bots can be purchased in bulk from companies that are part of a growing shadow economy specialising in online influence, making it that much easier to boost a political message or sow misleading information. Facebook and Twitter barely go a month without announcing a new wave of influence operations removed from their platforms, often numbering in the hundreds to thousands of accounts. But recent examples also show how difficult it can be to identify automation with confidence.

Bolivian President Evo Morales resigned in early November following protests, including from police, over disputed election results which culminated in the commander of the country’s armed forces calling on the leader to step down. Morales fled to Mexico and his allies in the region described the incident as a coup.

But in the immediate aftermath of his resignation, thousands of Twitter accounts started posting the message “in Bolivia there was no coup”, in both Spanish and English, in an apparent attempt to change the narrative.

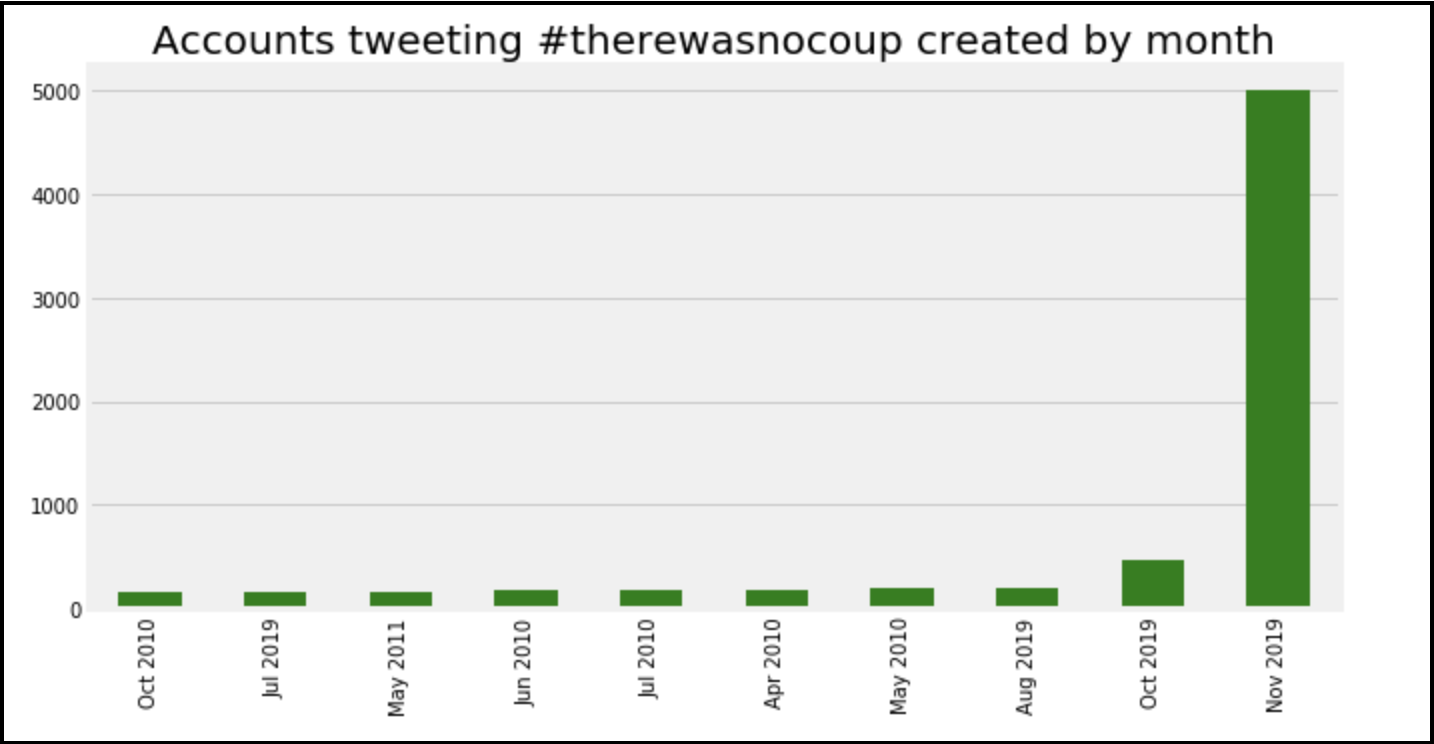

Of all the 17,427 accounts posting #bolivianohaygolpe, First Draft found nearly 30% were created this November. Nearly 5,000 were created on the 11th, the day after the Morales’ resignation.

But were they bots? A large number of brand-new accounts is certainly suspicious but jumping to conclusions over single indicators has tripped researchers up before.

A large proportion of the accounts tweeting about the political situation in Bolivia were recently created. Graph by First Draft.

In a study of 13,493 Twitter accounts that tweeted about the UK European Union referendum, Marco Bastos and Dan Mercea – both of City, University of London – identified various bot-like accounts that were actually human. They included @nero, operated by alt-right figurehead Milo Yiannopoulos, and @steveemmensUKIP, a British political campaigner.

Both were key nodes in the network of accounts identified as bot-like, proving that what appears to be a network of automated accounts can actually be the co-ordinated activity of real people.

While investigating suspicious behaviour on Twitter more recently, First Draft identified what at first appeared to be several bot accounts at the heart of a network pushing out the hashtag #takebackcontrol in support of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

The accounts had many of the hallmarks of a bot account, including a high volume of tweets and retweets as well as the use of awkward or inaccurate spellings and grammar. But upon closer inspection the accounts were actually manned by real people using Twitter to lobby and organise on behalf of their political cause.

And this kind of co-ordination isn’t just the prerogative of Twitter. The same activity can be found on Facebook.

First Draft looked at Johnson’s official Facebook page in the two weeks following the announcement of a UK general election. More than 40% of the posts on his official Facebook page were immediately followed by a tsunami of several hundred Facebook commenters who all repeated the same approving messages, such as “brilliant” and “fantastic”.

Many of the posts shared multiple examples of the message //”brilliant fantastic”&name=”Boris”code:syntax/error/, which appears like a broken line of code for instructing an automated account.

Some supporters of the UK Prime Minister were suspected to be automated accounts. Screenshot by author.

David Schoch, a sociology researcher from the University of Manchester, told First Draft the commenters were most likely bots whose goal was to “amplify the support for Brexit” but the BBC also looked into the issue and found real people behind these seemingly bot-like accounts, some of whom were actually posting snippets of broken code as a joke.

The automation arms race

Bots use snippets of code to relay content in an automated fashion. Simply put, they are accounts that automatically carry out a set of tasks.

Long before they became synonymous with international influence operations, bots existed online performing a range of benevolent jobs, from supporting your Google searches and warning of earthquakes to working in customer service.

Certain social media platforms, such as Twitter, have always been relatively bot-friendly, allowing for the automation of accounts. And many legitimate people and entities on Twitter – including journalists, academics, companies and everyday citizens – use bots to automate some of their day-to-day activities on the platform.

At the Italian National Research Council, Cresci spends much of this time developing techniques for detecting social bots and investigating the role of bots in the spread of disinformation.

He says bot creators didn’t put a great deal of effort into the automated accounts they built, at least not initially, and most people would be able to easily identify if an account was suspicious. And as the first bot-detection techniques emerged and platforms changed their terms to cut out malicious automation, bot creators changed tactics also.

“As soon as Twitter changes its procedures what happens then is [that] the bot creators have to develop a whole new set of protocols for automating their accounts,” says Andrew Chadwick, professor of political communication at the University of Loughborough.

These early methods relied almost entirely on what an account looks like in terms of their individual behaviour and account information, said Cresci, so creators responded accordingly.

“Some of the bot accounts we have seen in recent years have looked remarkably convincing and they have had lots of variation in their profile descriptions and images,” says Chadwick.

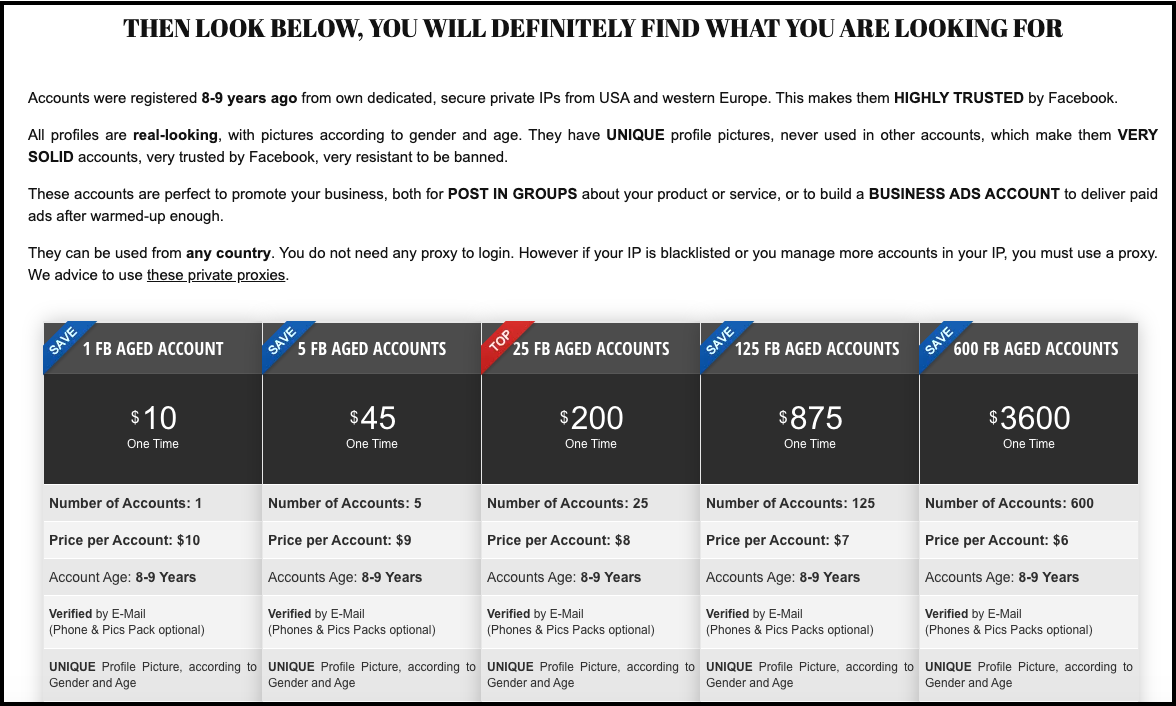

Some developers invest “months, sometimes years” in setting up accounts to appear authentic before selling them to the highest bidder, said Cresci.

“You can find an account with a lot of history that posted credible messages, credible tweets about a wide range of topics with videos from YouTube and songs and [which] generally [seems] pretty normal,” said Cresci. “And then suddenly it starts tweeting about politics and interweaving political tweets with the other stuff that it does, so it becomes very difficult to tell apart the good guys from the bad ones.”

Some websites offer ‘aged’ Facebook accounts to be bought in bulk. Screenshot by author.

Single bots are very well designed and engineered and it got very difficult to distinguish them from human-operated accounts,” said Cresci, as they are now often designed to mimic real humans, rather than just spam hashtags or topics. So, for Cresci at least, devising methods to spot “synchronisation and automation” is now the key.

“We cannot analyse one single account anymore, that does not work anymore. We have to analyse groups of accounts and analyse suspicious similarities between them.”

But not everyone does this the same way.

A myriad of models

Many researchers and academics are working on the issue of bot detection and some have developed extensive metrics for their detection. But while many of the metrics overlap, no two models are the same.

Botometer, developed at the University of Indiana, for example, uses around 1,200 different features of an account’s profile to deem whether or not it is a bot.

The IMPED model, on the other hand – developed in partnership with academics at City University London and Arizona State University – looks at linguistic and temporal patterns in tweets to deem whether the content is low quality.

And Cresci talks in terms of identifying the “digital DNA” of automation, modelling the activity of an account as a sequence of actions to then map onto other accounts to find the exact same behaviour.

“All of these things work to a certain extent because it also depends on the type of bot you are trying to spot,” said Cresci. “In the end I would say there doesn’t exist a single technique that is able to spot every bot.”

While this does cause some measurement challenges in terms of “understanding the scope, extent and reach of manipulated campaigns,” said Bradshaw at the Oxford Internet Institute, having different and evolving metrics is actually a boon.

“If we do have clear ways of measuring automation and clear standards on defining these accounts then the people who try to do the manipulation will just try to do something different,” she said, highlighting how transparency can be a double-edged sword in what has become an arms race between those doing the detection and those trying to dodge it.

“The more transparent that Twitter or academics or other groups are in defining these categories, the easier it becomes for people who are trying to do the manipulation, and the easier it becomes for them to game the system and avoid detection,” she added.

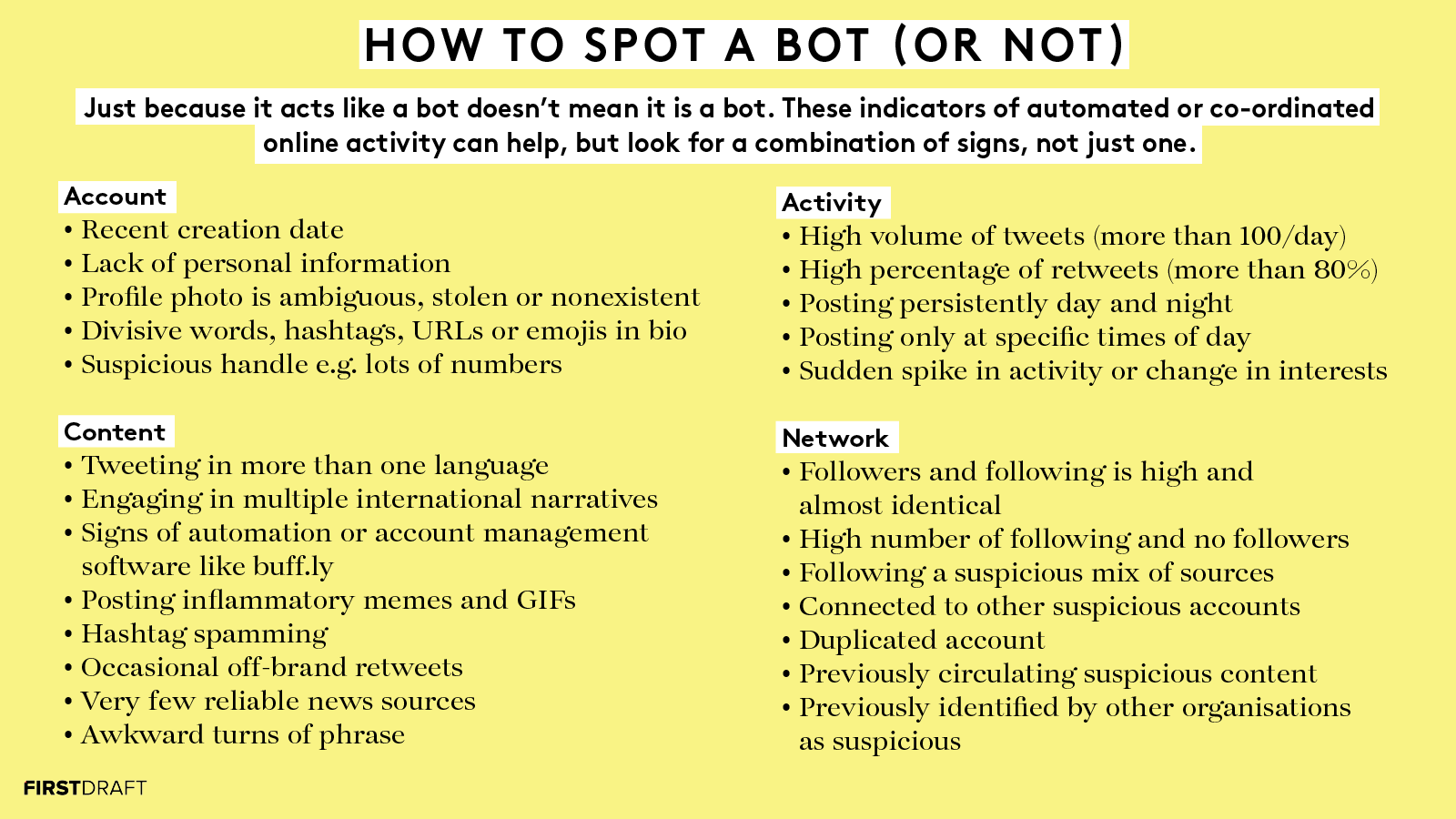

First Draft has pooled some of the main indicators for detecting inauthentic accounts, but given the rate at which technology and its corresponding disinformation tactics are evolving, the idea of coming up with a “yard-length rule that everyone can agree with” around bot detection is “a fool’s errand”, according to Chadwick.

First Draft’s indicators for spotting inauthentic activity.

Importantly, without different academics detecting the presence of large-scale automation and low-quality information on social media “it would also have been really difficult to get this information out of the platforms themselves,” says Chadwick.

A lack of data

Arguably the biggest obstacle to truly understanding the issue of bots is the continued lack of transparency from the platforms. Journalists, researchers and academics can only access small portions of the data on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, making it difficult to understand the full extent of the automation problem.

“Platforms should be open to collaborating and sharing and being more transparent,” says Bradshaw. “It would work for the benefit of the platforms in the long run but they are just so defensive now.”

But Twitter, along with top tier social media platforms, has to appease shareholders with growing revenue and stock prices, according to Chadwick. Because their interests aren’t necessarily aligned with ensuring transparency, there may be times when they are “in tension with a more public-minded or public-spirited role, which is to guarantee the security and authenticity of elections and other important political events.”

When it comes to defining bots, these misaligned incentives become particularly problematic, as “the people who have the best knowledge on how to define bots are working inside the platforms,” says Chadwick. “They are inside Facebook. They are inside Twitter.”

And as long as platform transparency eludes us it’s likely that any clear way of detecting bots will too.

Alastair Reid also contributed to this report.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.