LONDON – In early August, millions of people in the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir awoke to find their internet, landlines and mobile phones were no longer working. Later that day, the Indian government abruptly revoked the special status Kashmir had held for over six decades.

The Himalayan border region has been fought over by India and Pakistan since the countries were partitioned upon independence from Britain in 1947. India’s current ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has long promised its Hindu-nationalist base that it would fully integrate the Muslim-majority state.

Three weeks since the communications blackout in Kashmir was imposed on August 5, some phone services have been restored but the internet remains down. Some determined local journalists have reverted to filing stories on notebooks and distributing printed papers by hand, according to the New York Times. The editor of the Kashmir Times filed a lawsuit with India’s Supreme Court arguing that the shutdown violates press freedom.

Despite the blackout, Indian fact checkers have been kept busy by a steady stream of misinformation about Kashmir, from both supporters and opponents of the government’s move. But they are frustrated to have so little understanding of what rumours are spreading inside Kashmir. India’s government says the measures are necessary to prevent violence.

“Please try to understand the reasons behind these restrictions. Who uses phone and internet? It is of little use for us but is mostly exploited by terrorists and Pakistanis,” the BJP-appointed Governor of Kashmir, Satya Pal Malik, told reporters on August 28. “It is the most dangerous instrument… all lies are being peddled through the internet.”

In this age of information disorder, lies and rumours spread further and faster than ever. When the chaotic dissemination of misinformation online could inflame violence or even start a war, could it be safer to hit the kill switch on the internet? The Kashmir blackout highlights a crucial debate: can internet shutdowns ever be effective or justified in efforts to slow or halt misinformation?

‘A necessary evil’

India has had more internet shutdowns than any other country in the world – a total of 134 last year and 180 in Jammu and Kashmir alone since 2012, according to the Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC). Based in New Delhi, the legal services organisation tracks the growing frequency of web shutdowns through open source information, citizen reports and public information requests.

Nature of Shutdown:

Of the 278 reported incidents, 224 were targeted at mobile Internet services alone (3 in 2012, 5 shutdowns each in 2013 & 2014, 8 in 2015 and 20 in 2016, 51 in 2017, 126 in 2018 and 6 till January 2019), pic.twitter.com/Z1y3E2aR2D

— InternetShutdowns.in (@NetShutdowns) August 8, 2019

“Most [other] countries in which internet shutdowns have been imposed do not have a robust democratic political structure,” SFLC’s legal director, Prasanth Sugathan, told First Draft. “India, however, has frequently resorted to internet shutdowns despite being a democracy for 73 years.”

The internet is a particularly dangerous place in India. After a spate of lynchings fuelled by WhatsApp rumours, the Facebook-owned messaging service piloted its first forwarding limits in 2018. Researchers from Oxford University’s Computational Propaganda Research Project said the volume of polarising information online ahead of the 2019 Indian election was worse than any other country they had studied, with the exception of the 2016 US Presidential election.

Indian member of parliament Rajeev Chandrasekhar, a former telecoms executive, said that internet shutdowns are an unfortunate but necessary evil in India. “When there is a serious security problem internet shutdowns will be used,” he told Wired last October. “Even the purest, most utopian free internet advocate like me will have no option but to support it.”

‘Counter-productive’

Yet shutting down the internet can backfire. The lack of on-the-ground reports coming out of Kashmir can make it hard to fact check misleading claims. And while fact checkers look for clues to determine their authenticity, the misleading content has already gone viral.

“This time, the internet shutdown in Indian-administered Kashmir has actually led to rise of disinformation from social media accounts being operated from Pakistan… [claiming] to show atrocities by the Indian government,” said Uzair Rizvi, a fact checker for Agence France Presse (AFP) based in New Delhi.

“The other half of disinformation is being spread from social media accounts who sympathise with the Indian government, sharing old images or video trying to portray normalcy and calm in Indian administered-Kashmir,” he told First Draft.

As Indian administered Kashmir is under lockdown and all means of communications crippled. A lot of #FakeNews is being spread about the situation in Kashmir on social media.@AFPFactCheck has debunked several misleading claims, a thread on the fact checks published by AFP

— Uzair Hasan Rizvi (@RizviUzair) August 8, 2019

Recent misleading reports about Kashmir span the main categories of mis- and dis-information. A manipulated image (debunked by the BBC) falsely claimed that the Kashmiri flag had been removed from a government building. Another image (debunked by AFP) masqueraded as a genuine TV news bulletin about a ban on animal sacrifices in Kashmir.

Most common of all are images and videos taken from other contexts and recycled to show either turmoil or calm in Kashmir, depending on which side they are hoping to promote. Misinformation has been shared by media and politicians in India and Pakistan, as well as by the public.

The most widely-shared misleading claims appear in Facebook videos, Rizvi said. But it is factual claims circulating on text-messaging platforms which are particularly hard to fact check, he said.

“Several messages doing the rounds on WhatsApp about violence and deaths in Kashmir were very difficult to debunk as I had no way to contact authorities [in Kashmir] with all the means of communications blocked,” Rizvi said.

For Pratik Sinha, co-founder of Indian fact-checking site Alt News, the hardest thing is not knowing what information is circulating inside Kashmir that needs verification. “We have seen time and again that the lack of internet does not stop rumours,” he said.

Weaponising ‘fake news’

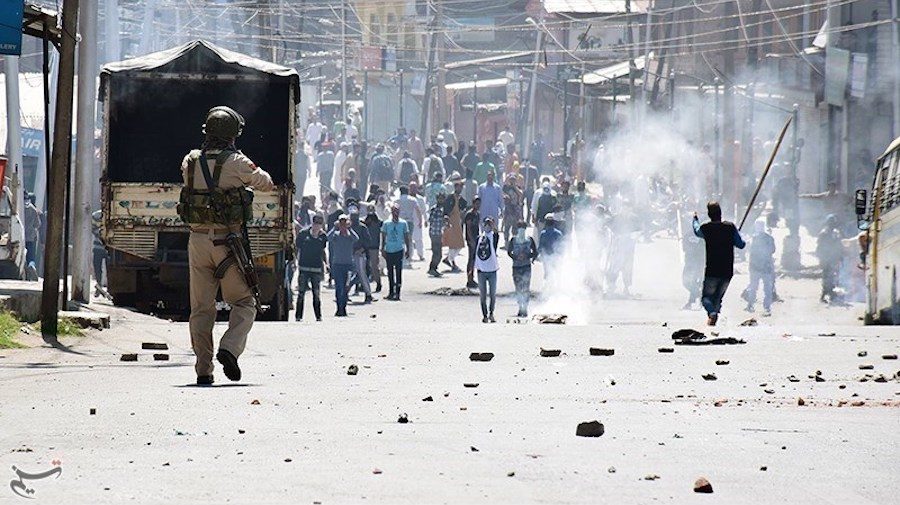

A week into the shutdown, Alt News verified a video that actually did check out. A BBC reporter in Kashmir had captured footage of Indian police firing on protesters. Reuters reported that 10,000 people had joined the protest after Friday prayers. The government cried fake news.

“This is completely fabricated,” a government spokesperson said. Officials said they had asked for the raw footage but foreign media outlets had not complied. The BBC’s PR department felt compelled to issue a statement refuting the accusations.

“There was a lot of backlash that the BBC was facing. It wasn’t just people on social media but also from mainstream media,” said Sinha. “That’s why it was extremely important to show that that it actually happened.”

This hasn’t aged well… https://t.co/vdNtEez2Gl

— Nicola Careem (@NicolaCareem) August 13, 2019

Sinha and a colleague worked to verify the timing and location of the BBC video. Their article determining its veracity received over 5,000 shares on Facebook – although in a country of 1.3 billion people, Sinha noted that reach is a challenge for fact checkers in India. But that’s not the only metric of success.

“The aim of fact checking is not always to change the perspective of the people, but also to stop the further spread of misinformation,” he said. “So that politicians and media are more circumspect about doing this propaganda on behalf of the government.” An Indian official later acknowledged that the protest had taken place.

“Rumours will always find a way [to spread]…It’s not that before the days of the internet we didn’t have any rumours,” Sinha said. “I’d rather have an internet connection, and have a way to cross-check things, as opposed to doing a communications blackout.”

Trust and truth

Another problem with shutdowns is that human nature abhors an information vacuum. The void is filled by polarisation and weakening of public trust, as each side holds onto its version of reality and brands its opponents liars, or loses confidence that anything is true.

This is deeply damaging to a democracy, which depends on a plurality of opinion and protecting the right to dissent, said Akriti Bopanna, a policy officer focused on free speech at India’s Centre for the Internet and Society.

“The veracity of information [about Kashmir] is much more in doubt now than if the internet had operated,” she said. “You automatically create distrust in the government.”

Losing internet access may even be counterproductive from a security point of view, Bopanna warned. She noted a recent study of protests during internet shutdowns in India by Jan Rydzak of Stanford University’s Global Digital Policy Incubator. He found that during outages, people are likely to “substitute non-violent tactics for violent ones that are less reliant on effective communication and coordination.”

6/ The key observation = each consecutive day of shutdown produces a surge of riots greater than what we usu. see with each consecutive day of protest. Meanwhile, the chances of shutdowns “succeeding” against nonviolent protest are not statistically different from random chance. pic.twitter.com/dTlNbL8fT6

— Jan Rydzak (言睿择) (@ElCalavero) March 23, 2019

Even though Bopanna is based in the Indian high tech hub of Bengaluru, more than 1,500 miles from Kashmir, she has felt some of the impacts of the blackout: friends who aren’t able to contact their loved ones; people unable to make online banking transactions. It’s been hard to get any clear sense of what people in Kashmir are going through and the range of political opinion there.

Bopanna recently met a woman from Jammu, a Hindu-majority part of Kashmir, who was hopeful that the government’s move would have positive benefits on corruption in the area. “With little information coming out you might take these views to be representative of the whole area, but are they?” Bopanna wondered. “This complexity [of opinion] is not well understood because of the communications blackout.”

Uzair Rizvi, the AFP fact checker, worries about the future trajectory of misinformation in the region. “By 2020, India will have around 700 million smartphone users, many of whom cannot read and write, but know how to use basic smartphones,” he said. “This propels a lot of misinformation which is also perpetuated by groups… and politicians are becoming very active on social media.”

And one of the main trends of misinformation in India, Rizvi said, is to inflame communal tensions. “This region is so diverse, with different cultures, ethnicities and religions,” he added. “Minorities everywhere share the maximum brunt of misinformation.”

To stay informed, become a First Draft subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.