As news breaks on social media, being able to verify posts, images and videos is an increasingly vital part of any journalist’s job. Storyful, the social newswire founded as a Dublin startup in 2010 before being acquired by NewsCorp in 2013, has arguably led the way in terms of tools and best practice.

At last week’s News Xchange conference in Berlin, Storyful’s managing editor Aine Kerr and director of news Mandy Jenkins led a workshop in verification practices for delegates.

Source, date, location

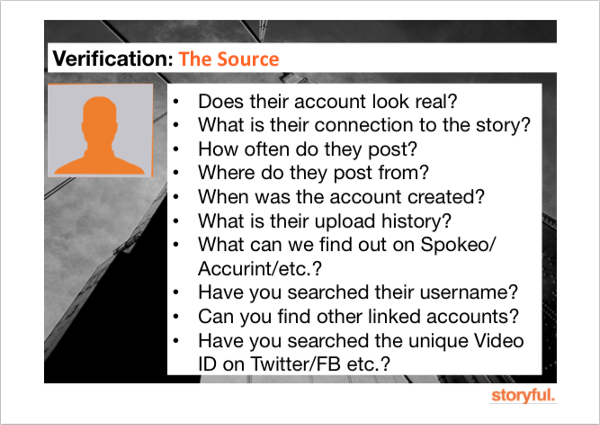

The core concepts journalists need to understand in proving the veracity of any piece of newsworthy material are its source, date and location, said Kerr, and there are certain methods to interrogate each, as should be done with any source.

“Getting in touch with the uploader is critical,” said Kerr, not only in terms of clearance to use an image but in getting closer to the story and finding more information.

Image courtesy of Storyful

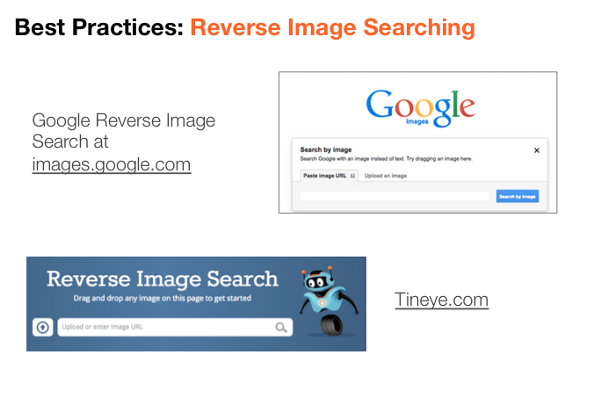

The aim when assessing the source is to conduct “a digital footprint analysis”, looking at the account’s history, any linked social profiles or websites, and searching for profile pictures through services like TinEye or Google’s reverse image search to see if it has been used elsewhere.

Particularly newsworthy pictures or videos are often “scraped” from the original source and re-uploaded elsewhere, and inconsistencies between a source and the content are often the first signs of a scrape. If an account that often posts about school life in California is suddenly sharing videos from Syria it is highly, highly unlikely they are the original uploader.

Tools like Topsy and Snapbird can be useful for analysing a Twitter account’s history, and if there are relevant blogs or websites Who.Is can help dig up extra information about the domain’s owner.

Who.Is played a major role in Storyful’s identification of Charleston church shooter Dylann Roof, for example.

Spokeo is also a powerful tool for searching US-based individuals and finding out more on their digital footprint — social media accounts, email addresses and other contact information — but it does come with a subscription fee.

Image courtesy of Storyful

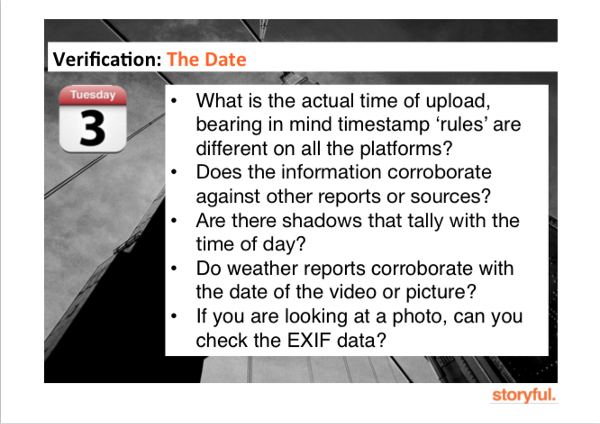

Timestamps from social are naturally the first point of call in terms of date, although it is important to be aware of the how timestamps differ on different networks. If viewing a tweet when not logged in, for example, the timestamp will show when the tweet was posted in San Francisco time, whereas it will show your local time when logged in, not the user’s.

Cross-checking the time and date with other reports or sources is also wise, but if you manage to speak to the original uploader and persuade them to send you a copy of the original file, EXIF data can answer a lot of questions.

Jeffrey’s EXIF viewer is a simple online tool to check meta data, but failing that Wolfram Alpha often helps Storyful to check information around weather in pictures when the metadata can’t be found.

Image courtesy of Storyful

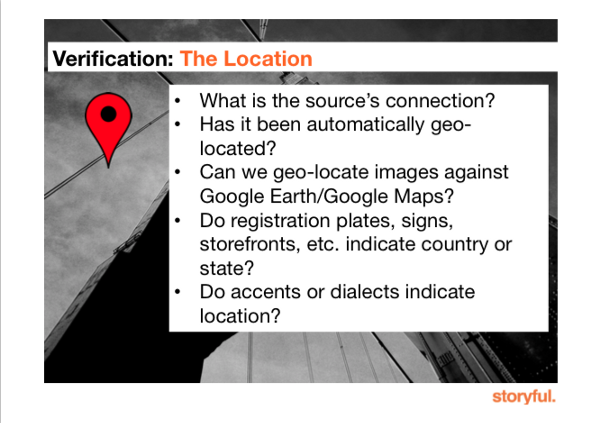

Most social networks will let users geotag an upload, although this isn’t always wholly reliable. If someone is uploading a scraped version of a piece of content then it will be geotagged to their location, rather than the original.

Again, getting the original file can bypass a lot these questions with the EXIF data, often showing the direction the photo was taken in, lat/long co-ordinates and more.

A “frame-by-frame analysis” of videos or pictures is often necessary for determining its location if all else fails, using information available in the material crosschecked on Google maps or other information sources. Street signs, shop fronts, landmarks and recognisable buildings can all be searched for or identified using satellite imagery.

So how does this actually work in practice?

Image courtesy of Storyful

The quickest test of an image is a reverse image search, said Jenkins, something “every newsroom should be doing”. Using TinEye and Google’s reverse image search, Storyful journalists were very quickly able to prove that pictures purporting to be from riots in Baltimore were old, she said, and a bit of digging into the offending accounts’ history showed them to be hoaxers.

February’s crash of a TransAsia Airway flight in Taipei proved a little more difficult, however.

The first news of the plane crash came from the English language Twitter account of a local news source in Taipei, Jenkins said, and subsequent searches on social media showed a number of pictures of plane wreckage and other reports.

Then one user posted photos to Twitter of the plane over a road, claiming the images were “some screenshots from [her] dashboard camera”.

Image courtesy of Storyful

“This is exactly what I always warn about,” said Jenkins. “The picture that is too good to be real, so compelling, so amazing, surely it can’t be real. This is spectacular. So we were very cautious about the photos.”

The second image gives some clearer details of the aeroplane itself, and using FlightRadar24 Storyful were able to find out the model of the plane that crashed. Digging for images of the schematics showed the picture to be a match.

Then came a video from YouTube of a similar scene, but from some distance back. The date and timestamp in the footage “certainly helped” and Storyful contacted the owner of the YouTube account to piece together the details.

Image courtesy of Storyful

“This being a video it’s a lot easier to get the details,” said Jenkins. “So for one thing we used the path of the highway, the signs and writing to get into Google maps and find this exact location based on the information that we can see inside of that video.”

Although the video was taken from further back, the first pictures could be matched to “a few metres” from the site of the crash itself.

Then another video emerged showing the plane crash from another angle. This appeared to be a scrape, however, “a dead end”, said Jenkins, but by piecing together a username found in an older video from that account and finding the same username on a Chinese gaming site, Storyful journalists traced the video back to a Facebook account and speak to the uploader.

The dramatic video the stills were taken from did eventually come out, licensed exclusively to a Taiwanese broadcaster, but the verification process was central in piecing together the story as it broke.

“From being able to compare these together, putting in all of that info from Google maps, the three different videos of the same scene, getting in contact with the original uploaders, we were able to place the plane, the location, the time of day, corroborate resources against one another and against media reports and were able to say these videos are real, this really happened and this is the actual crash.”

Aine Kerr and Mandy Jenkins were speaking at the News Xchange 2015 conference in Berlin.