By Carlotta Dotto, Rory Smith and Chris Looft

After November 3, some believers in the conspiracy theory that the US presidential election was rigged joined together, undeterred by official assurances of a fair and secure vote, to crowdsource evidence of massive fraud. They organized under hashtags like #DominionWatch, staking out election facilities in Georgia and doxxing voting-machine technicians. The ad hoc group investigation recalled the offline spillover of the QAnon-promoted #saveourchildren, which led participants to flood the hotlines of child welfare services with questionable tips about what they claimed was a vast child-trafficking conspiracy.

Empowering members to be an active part of a conspiracy theory’s development is fundamental to the QAnon community, which has been likened to “a massive multiplayer online game,” complete with “the frequent introduction of new symbols and arcane plot points to dissect and decipher.” And as the year closes, the community model of conspiracy theories has also energized #theGreatReset, which encourages participants to connect the dots between geopolitical events to form a picture of a nefarious plot by a shadowy world government to enslave the human race.

2020 was the year that demonstrated conclusively that effective disinformation communities are participatory and networked, while quality information distribution mechanisms remain stubbornly elitist, linear and top-down.

In trying to explain the influence of false and misleading information online, researchers and commentators frequently focus on the recommendation algorithms that emphasize emotionally resonant material over facts. Algorithms may indeed lead some toward conspiracy theories, but the dominant yet deeply flawed assumption that internet users are passive consumers of content needs to be discarded once and for all. We are all participants, often engaging in amateur research to satisfy our curiosity about the world.

It’s critical we keep that in mind, both to understand how bad information travels, and to develop tactics to counter its spread. We need to move beyond thinking of disinformation as something broadcast by influential bad actors to unquestioning “audiences.” Instead, we’d do well to remember that ideas, including false and misleading information, circulate and evolve within robust ecosystems, a form of collective sense-making by an uncertain online public.

Networks of amateur researchers can be formidable evangelists for their theories. A team of researchers led by the physicist and data scientist Neil Johnson found in a May 2020 investigation of online anti-vaccine communities that while the clusters of anti-vaccine individuals were smaller than those formed by defenders of vaccination, there were many more of them, creating more “sites for engagement” — opportunities to persuade fence-sitters. In our research into the “Great Reset” conspiracy theory, we found the content underpinning the theory had spread widely across Facebook in many local and interest-based spaces, garnering considerable opportunities to persuade the curious.

Crucially, the networks powering conspiracy theories like QAnon and the anti-vaccine movement are democratized, encouraging mass participation. On the other hand, the fact checks deployed against conspiracy theories almost always come from verified sources that are less than accessible to the general public: government agencies, news outlets, scientists. Networked conspiracy communities are proving resilient against this top-down approach.

The conspiracy theory network in action

This year, the World Economic Forum’s founder, Klaus Schwab, launched a messaging campaign calling for sweeping political and economic changes to address the inequalities laid bare by the coronavirus pandemic — a “Great Reset.” The language used by Schwab and allies, including Prince Charles and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, sparked a pervasive conspiracy theory that was advanced both by influential surrogates such as Fox News host Tucker Carlson and a diverse web of communities online.

To illustrate the networked dynamics that reinforce conspiracy theories as they did around the Great Reset, we examined that theory’s rise to prominence on Facebook, with an eye on the impact of the fact checks and debunks published by trusted sources in response.

We gathered 7,775 public Facebook posts that contained links and that mentioned “Great Reset” between November 16, when the conspiracy theory trended on Twitter, and December 6, and found that just a tiny fraction of the posts shared in that time included debunks or fact checks challenging the conspiracy theory.

Instead, the leading posts in our dataset advanced various aspects of the complex conspiracy theory. They warned of “globalist overlords,” a “socialist coup,” and an “organized criminal cabal” planning a “genocide.” The most-shared URL quoted Carlson referring to the Great Reset as a “chance to impose totally unprecedented social controls on the population in order to bypass democracy and change everything.” Fact checks appeared in just one per cent of the posts mentioning the Great Reset, and even then, some of the top posts linking to them came from accounts condemning the news outlets, such as in one post claiming “fake news and gaslighting,” further advancing the conspiracy theory narrative. The network of Groups and Pages, sharing these conspiracy theory URLs among one another, drove up the readership and engagement on those links, unhindered by the fact checks offered by traditional sources.

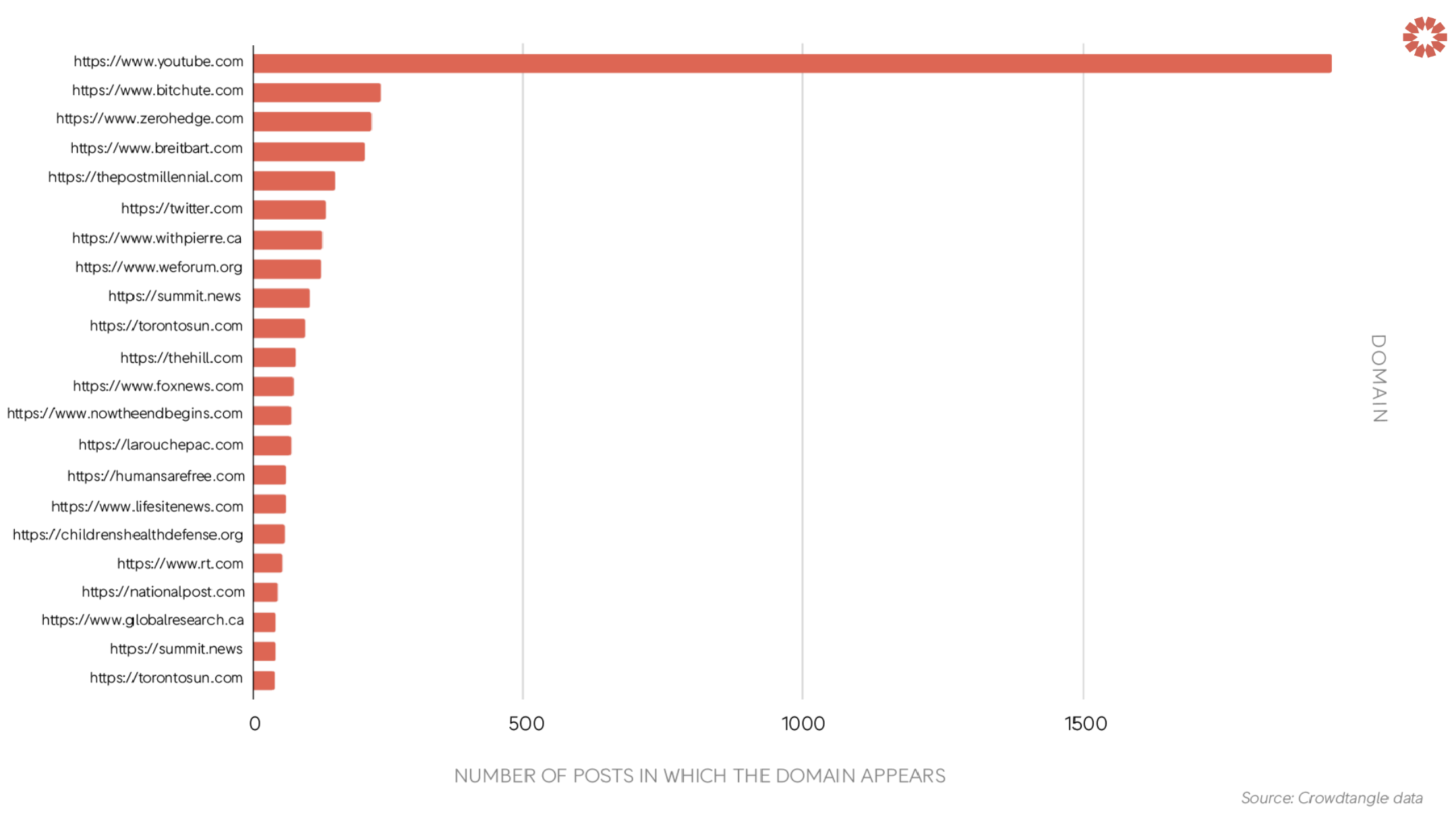

We took a look at the websites posted most often in our dataset and found that YouTube was the most popular domain, appearing in 1,945 posts — about a quarter of them — followed by BitChute, another video platform known for its far-right and conspiracy theory-related content.

Top domains in public Facebook posts mentioning the “Great Reset” between November 16 and December 6, 2020

After isolating the individual YouTube videos appearing in the dataset, we found that the 20 most-viewed videos all advanced a version of the conspiracy theory narrative. Together, as of December 17 they’ve been viewed nearly 9 million times on the platform. The widespread sharing of YouTube and BitChute links underscores how disinformation seamlessly skips among platforms, unhindered by moderation.

The prominent role of YouTube in the conspiracy theory makes sense, given what we know about the “echo chamber” of right-wing content on the platform. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm certainly plays a role in trapping viewers in echo chambers, also known as “information bubbles.” But more importantly, this content proliferates with the help of organic peer-to-peer networks that drive audiences to conspiracy theory URLs and videos.

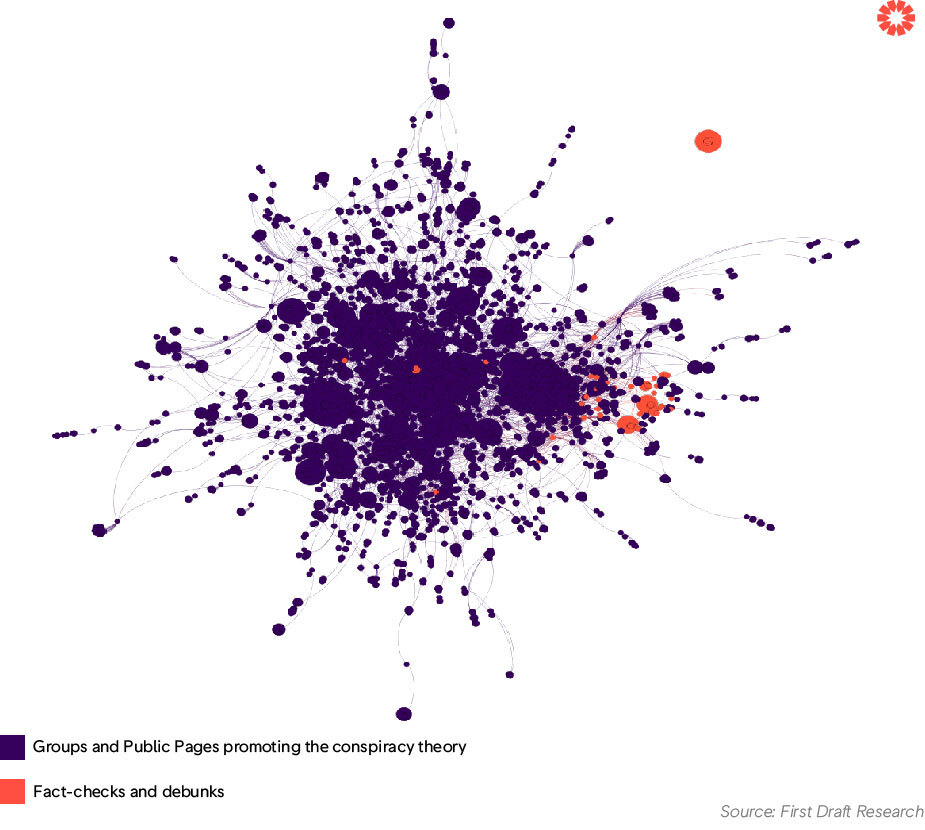

Visually mapping the ecosystem of Facebook Pages and Groups posting links about the “Great Reset” and the URLs most frequently shared in the set, we were able to find further evidence of the power imbalance between the conspiracy theory and the fact checks.

In the network visualization below, Pages and Groups that frequently share links among one another are grouped more closely together. The Facebook Groups and Public Pages promoting the conspiracy theory — represented by purple dots in the diagram — form a dense cluster of highly interconnected accounts, pointing to an ad hoc network that drives up engagement figures on conspiracy theory content. Importantly, we can’t conclude that the density of this network points to deliberate coordination. Rather, it suggests that like-minded Groups and Pages amplify a narrative by widely sharing, often among one another, the URLs and videos that advance it.

On the other hand, the orange dots representing fact checks and debunks spread in relatively small and isolated community clusters, remaining marginalized from the concentrated group in the center. The most frequently posted fact check — the Daily Beast’s “The Biden Presidency Already Has Its First Conspiracy Theory: The Great Reset” — couldn’t penetrate the core cluster of Pages and Groups championing the “Great Reset” conspiracy theory, even though its URL appeared in 37 different posts. The fact checks are having trouble keeping up.

The network of Facebook Pages and Groups sharing links about the “Great Reset”

Combating networked disinformation

A new approach is needed, one that moves away from “chasing misinformation” and instead proactively challenges and pre-empts its emergence. Rather than focusing on what messaging to send, and who should send it, we need to focus on initiatives based on co-creation and participatory strategies with existing communities. Public health professionals have shown the value of participatory strategies in dealing with rumors, falsehoods and stigma around HIV and the Ebola outbreak. The appeal to expertise inherent to traditional fact checking limits trusted sources, however large their audiences, from drawing on the same kind of participant networks that power effective communications strategies — as well as conspiracy theories. It won’t be an easy task, but in 2021, we’ll have to transform the fact-checking strategy built around the model of a one-way broadcast to one that addresses the complexity of disinformation networks before more fence-sitters are pulled into the fray.

Note on methodology:

We used CrowdTangle’s API to collect 11,808 posts from Facebook groups and unverified Facebook pages that mentioned “great reset” or “greatreset” between November 16, 2020 and December 6, 2020. We then filtered for posts that included outward links to other websites and social media platforms. To understand the potential impact of fact-checks on the conspiracy theory we also identified all the URLs from reliable news organizations that debunked the conspiracy theory and ran those URLs through CrowdTangle’s links endpoint to gather all the Facebook posts that shared them. These two datasets, which included a total of 7,775 posts, were then merged for analysis using Pandas and Gephi. In Gephi we re-sized the nodes based on the in-degree values in order to highlight the URLs that were most frequently shared in this set. URLs with more shares are represented by larger nodes. We used the “ForceAtlas 2” layout to bring accounts that frequently share among each other closer together.