This research was supported by a grant from the Rita Allen Foundation.

By Jaime Longoria, Daniel Acosta, Shaydanay Urbani and Rory Smith

Executive Summary

Hispanic people in the United States are nearly twice as likely as non-Hispanic white people to be infected with Covid-19 and 2.3 times as likely to die from it [1]. They are over-represented in frontline jobs, where they face higher levels of exposure, and they are more likely to have underlying health conditions that increase the severity of the disease [2]. While vaccination rates among Hispanic people have been rising, Hispanic people are still less likely than white people to have been vaccinated [3].

It isn’t possible to tell a single story about how this vaccination gap came to be. A history of medical exploitation and discrimination may play one role [4][5]. Data shows that language barriers, as well as concerns about immigration status, childcare and work schedules may also impede access to care [6][7].

All of these factors create a foundation of doubt and mistrust that allows misinformation about Covid-19 vaccines to flourish on social media. Unfortunately, little is known about how misinformation narratives emerge specifically in relation to Hispanic communities, how they circulate and how they ultimately affect people’s health choices. Yet understanding these dynamics is critical to creating strategies that dispel misleading information and help distribute quality information to those who need it most.

One of the biggest challenges to studying and understanding vaccine misinformation that affects Hispanic people is the lure of reductive categorization. In this report, we use both the terms Hispanic (primarily) and Latinx (secondarily). But both contain assumptions about language, identity and geography that fall apart under interrogation. The term “Hispanic” encompasses over 60 million people in the US, including Afro-Latinxs, Asian-Latinos, citizens, non-citizens and other groups with sharply different experiences. Not all speak Spanish, although they may engage with communities that do. Because of data restraints, in this research we were unable to disaggregate these many different populations.

With these challenges in mind, First Draft’s research team used a mixed-methods approach to collecting and thematically analyzing vaccine-related social media posts surrounding Hispanic communities. Specifically, we looked at the most engaged-with posts from unverified Facebook Pages, Facebook Groups, Twitter and Instagram from November 9, 2020, to September 9, 2021. During the same time period, we also monitored Spanish-speaking discourse and influencers on social media day to day, including on more fringe platforms such as Telegram.

The combined research is meant to provide insight to journalists, researchers and people in public health who want to understand and potentially act on problematic vaccine narratives as they relate to Hispanic people in the US. But it is also an attempt to bring nuance to important conversations that often get flattened: the difficulties of monitoring rumors across both English and Spanish, the borderless nature of online political discourse, and what it means to study misinformation “within Hispanic communities” when these same communities cannot be defined by a single race, history, culture or language.

- Full report: A Limiting Lens: How Covid-19 Vaccine Misinformation Has Influenced Hispanic Conversations Online (PDF)

- Una óptica limitante: de qué manera la desinformación sobre la vacuna ha influido en las conversaciones de los hispanos en línea (PDF)

What it means to study Hispanic misinformation

At the outset of this research, many questions necessitated answers before work could begin. These were questions that many in Latinx communities contend with each day and present as particular research problems to work from. One looming question was:

How best can one understand the online conversations and the flow of information in a nebulous community which largely resists the confines of the umbrella terms under which it has been placed?

There are drawbacks to terms such as Hispanic and Latinx. The former’s focus on a collective language is not only reductive, but inaccurate. Many within the relevant communities do not speak Spanish, though they may engage daily with people who do. The latter serves to further obscure the various racial and ethnic expressions that relate to the communities in question. Both identifiers largely exclude non-white people and predicate this group’s identity to a historical point of colonization. Latinx in particular attempts to disregard the persistence of colonialism. Nationalistic descriptors, such as Mexican-American, are often used as identifiers, but these are equally limiting.

This is an issue pervasive in reporting and research into these communities’ uptake of vaccines. Platforms, journalists, researchers and policymakers often see a benefit in flattening these nuances. However, this reduction results in the erasure of many people who are most vulnerable to vaccine misinformation.

To be clear, this group is not defined by a singular race, ethnicity, culture or language. Some are recent immigrants, while others have longer legacies of immigration. Some have no history of immigration at all. This group is not a monolith and insights or policies that do not take that into account do a disservice to these communities.

Culturally competent research under these umbrella terms then becomes a challenge. Many in this group experience dramatically different social and political realities which are leveraged within misinformation narratives. Cuban-Americans were notably on the receiving and producing end of narratives about socialism and communism surrounding the 2020 election, for example. That same year, in response to a summer of protests in reaction to the murder of George Floyd, anti-Black narratives took hold in these communities without singling out any specific Latinx experience. This illustrates the complexity and flexibility of narratives that gained prominence within these communities: Unique expressions, such as fears of leftist politics, are regularly exploited alongside universal ones, such as anti-Blackness.

In relation to vaccines, narratives about sterilization were among the most prevalent within these communities. Two groups in particular have a documented history of forced and coerced sterilization in the US, Puerto Ricans and Mexicans [8][9]. To what extent this narrative was crafted specifically for these communities cannot be known, nor can it be said that these communities were particularly susceptible to these narratives.

What can broadly be said is that this narrative was ever-present and popular in Spanish-language online spaces, regardless of the communities’ unique legacies confronting medical racism. Our research did not identify any significant instances in which vaccine misinformation narratives specifically leveraged a history of medical racism and trauma to amplify anti-vaccine sentiments, though these histories may have played a role in influencing baseline trust.

It would also be prudent to reference the public health failings that continue to affect these communities. Hispanics or Latinxs are 2.8 times more likely to be hospitalized for Covid-19 and 2.3 times more likely to die from the disease than non-Hispanic whites [10]. Many community members had lost their faith and trust in the institutions that were supposed to help them, First Draft learned from work with community-based organizations. This ranged from governments and politicians to local hospitals and healthcare workers who may have had to turn away gravely ill patients for lack of capacity. These factors can have a significant impact in baseline trust in the same institutions that are now participating in the vaccine rollout.

Monitoring information disorder in these communities is as nuanced as Hispanic communities themselves. Cultural competency is beneficial in research, but daily monitoring presents a number of challenges. The use of keywords and Boolean searches will only take you so far. Not only are conversations of interest stratified into the many varieties of Spanish, but a considerable number of conversations within and about these communities also take place in English.

Taking geography into account presents another challenge. Not only is it at times unclear whether a misinformer or narrative comes from the US, but monitoring must also take into account how easily narratives from outside the country can become prevalent in the US via diaspora communities or translation into English. Borders — even online — occupy a political imaginary that does not always reflect reality.

Reliance on lists of repeat influencers culled from investigations of popular narratives provides one solution to this problem, but these lists must be large enough to be able to detect popular narratives. Otherwise, they provide a myopic view of the information landscape, often reflecting the researcher’s own propensity for certain topics or groups within Latinx communities.

These communities exchange a considerable amount of information in difficult-to-research online spaces. Not only do Hispanics and Latinxs spend more time on social media, they are over twice as likely to use messaging apps, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, than the general population [11].

Although some access is possible on Telegram, which also provides the number of times a specific message has been seen, WhatsApp has proven difficult to monitor. In many ways, this gap in knowledge also limits many efforts in combating vaccine misinformation. Covid-19 vaccine misinformation on WhatsApp is much like an iceberg: Only a small portion of what is shared ever surfaces, and when it does, there is no way to know how many times the content was seen. Messaging apps are an effective way of spreading mis- and disinformation to wide audiences. Many influencers rely on these messaging apps to skirt moderation from other social media platforms. They also serve as tethers to their audiences if their other accounts are removed.

These are not the only unseen exchanges of information that should be of concern to better protect communities from Covid-19 vaccine mis- and disinformation. The proverbial dinner table is an often-neglected area of inquiry, yet many of the most impactful conversations take place among communities where interpersonal relation is centered. Public health advocates must be willing to trust that, with adequate resources, trusted messengers who have stakes in their communities can be among the most effective messengers.

A focus on access must play a central role in any vaccine rollout. But getting someone vaccinated doesn’t always mean providing them access to vaccines. For many in vulnerable communities, there are a number of needs that must be addressed before vaccination can take precedence. This means that at times, vaccinating a member of the community first means providing adequate and safe housing, for example. These factors, coupled with misinformation, have a compounding effect on hesitancy if not addressed and any approach that attempts to solve hesitancy without taking into account equity will likely have limited success.

Platforms’ reliance on machine learning algorithms presents another challenge in curbing online misinformation. More must be done to understand the central role of these mechanisms that control users’ experience on platforms and often puts them in contact with harmful content. This, and not moderation, is the central issue in addressing mis- and disinformation online. Incendiary and controversial content outperforms on these platforms by design. Additionally the use of large language models in automated moderation, which have been considered largely deficient, if not dangerous, in less sampled languages, must be interrogated [12]. Misinformation is not a problem that can be solved solely with interventions designed to work only in English.

Key findings

Narratives concerning the safety of Covid-19 vaccines were among the most widespread and impactful on social media. These narratives were diverse, ranging from claims that vaccines would cause sterilization, lead to death and were rushed into production. These messages were delivered via equally diverse formats, but videos of alleged adverse reactions in particular were easy to share and easily accessible to their intended audiences. Overall, these narratives co-opted pre-existing barriers in trust — historical and contemporary — and highlighted the indemnity given to vaccine producers. Historical fears and anxieties concerning US medical institutions, though, were never leveraged outright. This may be because of the varying histories Hispanics have when interacting with these institutions, but it is impossible to say that these did not play a role. Many in these communities may have found it equally difficult to trust in institutions involved in the vaccine rollout, as these are the same institutions that failed them during the pandemic.

Narratives concerning alleged “alternative treatments” were among the most influential in Spanish-language online spaces. Herbal teas, baking soda shakes and ginger-based drinks were commonly amplified in Spanish-speaking online spaces. Among them were other more potentially harmful substances such as chlorine dioxide solution (CDS) or miracle mineral solution (MMS), as it is called in English. Although not new, the use of this powerful bleaching agent became widely popular in a number of Latin American countries and was touted to diaspora communities in the US who could acquire it via online shops, such as Mercado Libre (in Latin America) and Amazon. References to medications and supplements such as dexamethasone, hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin and zinc were present in Hispanic communities even before they were championed by US anti-vaccine communities.

Satirical and sarcastic posts will frustrate attempts to use machine learning models to understand vaccine conversations surrounding Hispanic communities and may amplify misinformation. Satirical and sarcastic posts featured heavily in vaccine-related Spanish-language conversations on social media. The nuances of these posts — the humor is subtle and posts employ different context-dependent slang — will complicate efforts at building machine learning models that accurately represent vaccine-related conversations in Hispanic spaces. Moreover, many of these satirical posts contain the same misinformation and conspiracy theories at which they are poking fun. These posts could lead to the overrepresentation of conspiracy theories by machine learning classifiers. If published and reported on without taking these biases into consideration, they could amplify misinformation and a false understanding of these conversations.

Religious figures have played a pivotal role in the spread of Covid-19 vaccine misinformation in Spanish, leveraging their positions of power and authority in these communities. Many religious figures already had a robust online presence. But others brought a devoted following online when in-person services came to a halt because of the pandemic. Nevertheless, these religious figures were at the forefront of narratives that pushed “alternative treatments” and false claims that Covid-19 vaccines contain microchips, change recipients’ DNA, contain aborted fetuses and are the work of the Antichrist. Many of these claims were widely shared, becoming ubiquitous continuing to fuel confusion and mistrust today.

Spanish-language misinformation is not solely reliant on the translation of English-language narratives and is influential in its own right. Hispanic communities have their own roster of notorious misinformers who work to amplify and distribute misleading and harmful information in English and Spanish. While this is true across platforms, these misinformers have a propensity for messaging apps, which provide a space where moderation is more easily evaded. Notably, our research followed narratives of graphene in vaccines from their inception in Spanish, where we first detected them. It was months later that these narratives became prominent in English-language online spaces. The spread of misinformation is not linear. Misinformation originating in Spanish may become popular in English and vice versa. It is important to consider how these distinct spaces and communities interact and exchange ideas to better inform solutions. The problem cannot be solved only in English.

Closed network apps used widely by Hispanics, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, provide an infrastructure to amplify misinformation, skirt moderation and create tight-knit communities based solely on the sharing of misinformation. Despite limited action from some platforms, such as Facebook, to slow the spread of misinformation, closed network apps continue to provide safe haven for many misinformers. These spaces allow for the largely unchecked spread of claims, allowing discussions in these groups and channels to become constant feeds of misinformation. A number of influencers rely on these closed messaging apps to maintain a stable audience when their presence on other platforms is at risk, limiting moderation efforts. These spaces are notorious for their lack of moderation and are exceptionally difficult to monitor and research. Finally, these apps have been effectively leveraged to foster community around misinformation, leading many users deeper into extreme and conspiratorial anti-vaccine online spaces.

Social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram have provided ample space for Spanish-language misinformers to grow their audiences internationally and perpetuate the spread of Covid-19 vaccine misinformation. Activist organizations such as Médicos por la Verdad (Doctors for the Truth) and Coalición Mundial Salud y Vida (Comusav) play a pivotal role in spreading vaccine misinformation and promoting the use of hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin and chlorine dioxide solution. Through various strategies, including the use of social media platforms to promote junk science, conferences, lectures and outright conspiracy theories, these groups have been able to amass a diverse and international audience. A number of misinformation and hyperpartisan outlets are positioned to easily disseminate anti-vaccine content to a wide audience; at times they translate and republish content from other notorious health misinformation sites. Independent anti-vaccine influencers and translation-focused cooperative campaigns by misinformers play a similar role, often translating memes and subtitling and dubbing videos into Spanish with the goal of amplifying popular English-language narratives to their sizable followings.

First Draft’s work with community organizations sheds light on the limitations of online monitoring of information disorder, as well as the role that misinformation plays in communities. The conversations we see online are not always reflective of the narratives that may be spreading within specific Hispanic communities. Qualifying what should and should not be monitored when researching narratives in these communities is difficult. Not only must this research take into account identity and geography, but also language. This also becomes a challenge when monitoring more locally, as intimate knowledge of these concentrated information ecosystems becomes necessary. The difficulty of monitoring closed messaging apps contributes to these challenges. Many of these conversations take place offline at religious services, barber shops and the dinner table, underscoring the importance of direct community intervention. Without understanding the direct effects of misinformation on personal and political decisions, we will be unable to effectively measure its impact. More research is needed to understand how these factors relate to real-life action.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Platforms and journalists must expand their idea of Hispanic communities. Umbrella terms and US-centric cultural associations of who is included and who is not continue to limit how platforms, journalists, researchers and organizations address information disorder within Hispanic communities. These stakeholders must acknowledge the diverse set of communities that fall under these umbrella terms. Otherwise, the most vulnerable members of these communities — along with those who have strong ties to them — will continue to bear the brunt of mis- and disinformation. The greatest failures come from the platforms, which have failed to provide a safe infrastructure for the exchange of reliable health information in languages other than English.

Recommendation 2: Platforms must commit to combating Spanish-language information disorder with any available tools, recognizing that these measures are merely stopgaps. Although reform must go further than focusing on lackluster and unevenly applied content moderation, enforcement in Spanish continues to be lacking [13]. Moderation of Spanish-language content is the bare minimum of need on social media platforms. Culturally informed and competent moderation supported by resources and efficacy rivaling what we see in moderation efforts in English will be necessary, though this on its own is not enough. Given the diversity of the Spanish language — each Spanish-speaking country has its own region and context-specific lexicon, including political dog whistles — as well as the use of Spanglish in many social media posts, attempts at automating the detection of vaccine misinformation with machine learning will likely miss important signals.

Recommendation 3: Social media platforms must provide journalists and researchers with better access to data and transparency around the kinds of data they receive. In the absence of independent watchdogs with access to platform data, these same social media companies are the only entities equipped to fully understand these information ecosystems and monitor concerning trends. However, their work is limited by insular platform policies that prioritize profit and public image over accountability. Providing journalists and researchers with better access to social media data is one of the only ways we can truly hold these platforms accountable. This is especially important when tackling information disorder in Hispanic communities and communities of color. Many of the misinformers from these communities have smaller but highly dedicated followings. Yet because these conversations are smaller in scope compared to more mainstream vaccine discourse on social media, they easily evade the marketing tools, such as CrowdTangle, that researchers and journalists have repurposed as research and monitoring tools.

Recommendation 4: Platforms must commit to policy transparency and eliminate uneven enforcement. The lack of policy transparency around moderation — why one post is removed and another is not — has allowed platforms to skirt responsibility for allowing harmful users and content to remain on the platform. Approaching the 2020 presidential election, notable Hispanic misinformers had built dedicated followings by amplifying incendiary hyperpartisan and misinforming content. For months, many of these users went unchecked. While a number of these users had accounts removed, some users were reinstated or relied on backup accounts that assured they were active during the election. And although these misinformers usually had smaller audiences than other bad actors who target broader communities, their misleading content often received disproportionately high rates of interaction. This issue extends further than platforms’ racialized user base; known misinformers are often featured among the most shared and popular content on a number of platforms.

Recommendation 5: Platforms must contend with the challenge of balancing privacy and public interest, especially in communities that rely on closed messaging apps as primary modes of communication. Hispanic young adults are over twice as likely to use WhatsApp and Telegram than the general population, yet these are among the least moderated and most difficult to research platforms [14]. Open and transparent data access on these platforms is vital in understanding how these mostly opaque information ecosystems function and whether any actions taken by platforms to limit information disorder have been effective. Privacy and security are important, especially because these platforms are widely used for communication in politically hostile environments, but there still must be mechanisms in place to assure an exchange of reliable information.

Above all, the ability to understand community conversations, such as those in semi-closed spaces — groups and broadcast lists on WhatsApp, for example — would be beneficial, with the understanding that these are distinct from private conversations that take place on these platforms. It is, however, prudent to consider at what number of participants a conversation would become a matter of public interest. We also recommend the implementation of more robust and transparent interaction metrics as well as labeling features, but these must be implemented globally. In closed messaging apps, enforcement actions against users and content, other than relating to sexually explicit material, seem more concerned with disincentivizing spam, not harmful information. This falls in line with efforts to keep users on the platform and not necessarily to prevent information disorder. This priority must shift.

Recommendation 6: It remains important to validate the complex and diverse lived experiences that members of these communities have when accessing health care in any conversation about vaccines. Not only are many informed by a history of medical racism, which includes forced and coerced sterilization, a number of cultural and linguistic barriers have continued to impede access to care [15][16]. Decade-old Census data suggested Hispanics were the least likely group to seek out a medical provider [17]. Hispanics were over two times more likely to be hospitalized or die from Covid-19 than non-Hispanic whites [18]. These factors contribute to a baseline mistrust that has been further exploited online. Narratives about vaccine safety, including claims of sterilization, dominate in these communities, for example. Additionally, from First Draft’s work with community-based organizations, organizers repeatedly expressed that community members had also lost trust in institutions that failed them during the pandemic.

Recommendation 7: The news media must commit to creating a robust infrastructure that serves the diverse interests of Hispanics and those with ties to these communities. Demand and need for reliable and culturally informed information exists because Latinxs are more likely to encounter hyperpartisan content or misinformation; 28 per cent of websites with a 20 per cent Latinx audience were flagged for this type of material in a September 2021 Nielsen report [19]. Hispanic millennials are also highly dependent on YouTube for daily news and information [20]. But whatever form this infrastructure comes in, it must go further than Spanish-language networks, heritage month specials and diversity verticals. The interests of these communities must be integrated into and represented by the dominant day-to-day news cycle. Latinxs accounted for over 50 per cent of the US’ growth, while a substantial number prefer to get their news in English [21][22]. Hispanics are more likely to trust English-language news overall [23]. These efforts must go further than diversity initiatives. Adequately reflecting the growing audience of political stakeholders would require a cultural shift in newsrooms to serve these complex communities sufficiently.

Recommendation 8: Centering equity, accessibility and overall wellness in vaccination strategies can prove beneficial to vaccinating Hispanics and those with ties to these communities. The reach and sway of misinformation is difficult to quantify, but information disorder about Covid-19 vaccines can reinforce pre-existing obstacles to vaccination. Factors such as disability access, physical safety, language, immigration status, homelessness, transportation, technology, childcare and concerns about impacts on work schedules and pay are some of the concerns community organizers must contend with, First Draft has learned. It is important to recognize that for some members of these communities, there are a number of more immediate needs that outweigh vaccination — and without satisfying these needs first, inoculation will not be a priority.

Recommendation 9: Do not neglect bottom-up approaches in vaccine messaging; centering education via community and interpersonal relationships can prove extremely effective. Celebrities and well-known influencers have been leveraged to demonstrate to the public the safety of Covid-19 vaccines, but this approach raises skepticism among some because these individuals are only superficially trusted. True trusted messengers are among friends, family and community; many have already been tasked with having difficult conversations about the vaccines’ safety and efficacy with others in their lives [24]. It is paramount that resources go into educating community-based trusted messengers and equip them with enough knowledge to continue to have these conversations. Messaging must shift from informing the public they should get vaccinated to informing the public that they too can help their community become vaccinated — provided those resources are in place to help them.

Recommendation 10: Public education about the risks and dangers of social media’s effects must become more normalized. To a large extent, much of the general public does not understand platforms’ lack of accountability and complicity in allowing information disorder to become a mode of profit. Nor is the general public fully educated on platforms’ use of machine-learning algorithms that control people’s experiences and drive them to harmful content. An extensive public education effort might help inform and shift public skepticism about the information consumed on these platforms. The veneer of infallibility of these platforms, which have become direct sources of information for many Hispanics, must be dismantled.

Recommendation 11: Platform reform efforts must focus on ensuring more algorithmic transparency from social media companies. In the past, social media platforms have leveraged machine learning algorithms and models that prioritized the growth and retention of their user bases over credible information and the safety of their users [25]. This has incentivized the spread of highly emotive, harmful and unreliable content [26][27][28]. Social media platforms claim they have amended these models, such as Facebook’s news feed, to prioritize reliable health information. However, because social media companies are unwilling to allow researchers to inspect these models, it’s impossible to know whether these supposed changes have had any real effect [29]. Platforms must commit to more algorithmic transparency. In the context of communities that speak languages other than English, such as Hispanic communities, language models used in platform moderation efforts must also be vetted. The self-auditing of platforms is no recipe for transparency. To ensure better transparency and protect users on these platforms, objective third parties, such as academics and researchers, must be able to step in and audit the models underpinning these platforms.

Background

Hispanic communities in the US have been disproportionately affected by the Covid-19 pandemic compared with white people. Because Hispanic people are over-represented among those working essential and frontline jobs, they experience greater exposure to Covid-19 without the health benefits that come with other types of employment [30]. Due in part to poorer socioeconomic conditions, Hispanic people are also more likely to have underlying health conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, asthma and obesity, leaving them more likely to develop acute cases of Covid-19 [31][32]. Around 30 per cent of Hispanic homes are multigenerational [33]. While there are many benefits of living in a multigenerational home [34], it also puts families at a higher risk of being exposed to Covid-19 [35][36]. Among all ethnic groups in the US, Hispanic people have the lowest rates of health insurance coverage, discouraging them from seeking health services [37][38].

Despite Hispanic people making up 18.5 per cent of the US population, these factors have contributed to Hispanic people accounting for 26.9 per cent of Covid-19 cases [39]. Furthermore, Hispanic people are currently 1.9 times more likely to develop Covid-19, 2.8 times more likely to be hospitalized and 2.3 times more likely to die from the disease than white people [40].

Covid-19 has also had a disproportionate impact on Hispanic communities in other ways. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), 50 per cent of Hispanic parents said they had at least one child who fell behind academically during the pandemic [41]. And 60 per cent of Hispanic parents said the pandemic has negatively affected their mental health [42].

Vaccination rates among Hispanic people have been increasing over time, but Hispanic people are still less likely to have been vaccinated than white people, putting them at increased risk of being exposed to Covid-19 [43]. And significant geographic differences in vaccination rates remain. While in Vermont 97 per cent of Hispanic people are vaccinated — it’s one of the few states where more Hispanic people have been vaccinated than white people — in Colorado and South Dakota, for example, only 36 per cent and 4 per cent of Hispanic people have been vaccinated compared to 68 per cent and 51 per cent of white people respectively [44].

As boosters are rolled out, kids head to school, vaccines open up to children under 12 and the winter months approach, closing the vaccination gap by increasing Covid-19 vaccine uptake among Hispanic people will be vital to mitigating the disproportionate health, economic and educational impacts that Covid-19 is having on these communities.

Many Hispanic people are eager to get the Covid-19 vaccine, but they still face obstacles [45][46]. Structural hurdles to access, such as work and family responsibilities, transportation, language barriers and, as a consequence, low levels of health literacy (the ability to access and make sense of health information and then make decisions based upon it), fear of immigration enforcement at vaccination clinics as well as of having to pay exorbitant prices for healthcare have all discouraged efforts by many Hispanic people to receive the Covid-19 vaccination [47][48].

Deeply ingrained mistrust of the government and the healthcare system is another significant barrier to getting vaccinated for Hispanic people [49]. Hispanic people have also been subject to medical exploitation and discrimination in the US, resulting in many mistrusting medical institutions [50]. Around one-third of Puerto Rican women were sterilized between the 1930s and the 1970s as part of a plan to control population growth [51].

Birth control pills were also tested on poor and marginalized Puerto Rican women [52], using pills containing three times more hormones than modern-day pills. Not only were these women not told that they were part of an experiment, but the side effects they experienced were ignored [53]. And in California between 1925 and 1940, Mexicans were disproportionately sterilized as part of a statewide eugenics program [54].

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, 60 per cent of Hispanic people believed that “research misconduct by medical scientists” was a problem, according to the Pew Research Center [55]. And according to one recent study, nearly 33 per cent of Hispanics in the Los Angeles area didn’t trust the government to develop a Covid-19 vaccine [56].

Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation and the University of California, Berkeley has shown that anti-immigration rhetoric and immigration policies by the Trump administration made it harder for non-citizen immigrants to access healthcare services during the pandemic [57][58]. They also continue to fuel mistrust and fear of immigration authorities, discouraging many Hispanic people from seeking out Covid-19 vaccines at vaccination sites [59][60].

Vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories on social media are compounding these issues. While misinformation can fuel mistrust in Covid-19 vaccines and reduce intent to get vaccinated, the relationship isn’t one-way; mistrust also makes people more likely to be vaccine hesitant and more receptive to misinformation [61][62][63].

Misinformation on social media is particularly problematic for Hispanic people, many of whom are native Spanish speakers and communicate in Spanish either at home or with family in other countries. On certain platforms, such as Facebook, content moderation policies are being exercised less effectively in languages other than English, according to researchers [64]. A new report from Nielsen shows that Hispanic people are large users of encrypted messaging applications — those ages 18-34 are more than twice as likely to use WhatsApp than the general population — where content can’t be fact-checked, putting them at risk of being exposed to misinformation[65][66]. A Voto Latino poll of Hispanic people in April found that 78 per cent of respondents believed Covid-19 misinformation played a large role in discouraging Covid-19 vaccine uptake [67].

Efforts to build trust and encourage vaccine uptake among Hispanic populations will need to address the key narratives and vaccine-related misinformation circulating online. While addressing misinformation isn’t enough on its own to address vaccine concerns, used in conjunction with community outreach efforts, the identification of key online narratives and misinformation can help to dispel misinformation, build trust and close the vaccination gap for Hispanic people.

Methodology and Limitations

Identifying vaccine-related posts on social media is a fairly straightforward task, which in essence requires a detailed set of vaccine-related search terms in the applicable language. However, identifying vaccine-related posts as they pertain to a particular demographic is more challenging, given the lack of publicly available metadata that might provide this kind of robust information.

Without access to this data, it’s nearly impossible to determine who is behind each social media account, which complicates efforts to isolate accounts operated by or posts emanating from individuals who identify as Hispanic. While determining the identity of Instagram and Twitter accounts may be feasible in some instances, especially if you are monitoring an account’s day-to-day activity over a long period of time, ascertaining whether that person is 1) actually operating the account and 2) the only individual operating that account will always remain a challenge.

As a result, we were unable to identify posts emanating from only accounts operated by individuals identifying as Hispanic. Researchers manually monitoring and analyzing social media content on a daily basis attain familiarity with the nuance of online conversations in Hispanic communities, which allows for more confidence in determining whether the accounts engaging in vaccine conversations are primarily Hispanic and their messages aimed at Hispanic people. Nonetheless, because we examined public data and posts — posts that anyone irrespective of demographic could access — and because we suffer from the same data limitations listed above, it’s difficult to say whether this content was aimed at and consumed exclusively by Hispanic people.

To get as close as possible to posts relating to and affecting Hispanic people on social media, we used a two-pronged qualitative mixed-methods approach (detailed below). It combined specific keywords and Boolean operators in English to gather posts that we believed were either created by, aimed at and/or consumed by Hispanic people.

Because many Hispanic people are bilingual, or exclusively Spanish speakers, and communicate with friends and family in the US and abroad in Spanish, it was important to capture Covid-19-related posts in Spanish [68]. Geofencing social media data to one particular country, such as the US, is a major challenge because of Facebook’s reluctance to share robust data with researchers. While Twitter offers more transparent access to its data, many users on the platform elect to keep their location hidden. Furthermore, we know that the spread of information on social media is borderless and that language often serves as the best predictor of the spread of information [69]. For example, posts emanating from Spain are likely to end up in Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America and in the US and vice versa.

Through our daily monitoring of health misinformation over the past few years, we observed that Spanish-language misinformation coming from outside the US inevitably makes its way into the information ecosystem of Hispanic people in the US. As such, we also included posts in Spanish that related specifically to Covid-19 vaccines.

In addition, we undertook manual daily monitoring of Spanish-language influencers on social media. At best, the data we analyzed and the social media activity we monitored approximate posts coming from, relating to and consumed by Hispanic communities in the US. However, they may not all emanate from individuals identifying as Hispanic.

It’s important to remember the term “Hispanic people” doesn’t represent a homogeneous population. There are 62 million people in the US who make up the incredibly diverse Hispanic population, including Afro-Latinxs, Asian-Latinxs, Mexican-Americans, Cuban-Americans and Argentine-Americans, among many other distinct groups. Furthermore, there are many Hispanic people who are non-citizen immigrants, whose precarious immigration status and lived reality in the US contrasts sharply with those Hispanic people who are US citizens. However, because of the aforementioned data constraints, we were unable to disaggregate among these many different populations.

The aim of this research report was to both identify the top vaccine-related narratives on social media possibly influencing Hispanic communities, as well as to better understand the information ecosystem surrounding them. This includes, among other things, identifying trends and threats that might make individuals more vulnerable to misinformation and how platforms respond to Covid-19 vaccine misinformation related to these communities.

As such, we opted for a qualitative-centric mixed-methods approach that combined 1) static analysis of the most engaged-with vaccine-related posts surrounding Hispanic communities from November 9, 2020, to September 9, 2021, with 2) dynamic analysis of posts through our day-to-day monitoring of Hispanic-related spaces on social media during that same time period.

Taking slices of data, such as the most engaged-with posts, is useful for determining the top themes and narratives during a particular time frame as it allows us to support what we find qualitatively with quantitative data (engagement metrics). However, because this approach is static — it isolates data during a particular time period — it misses much of the nuance and dynamics at play within a specific information ecosystem — in this case, vaccine discussions on social media consumed by Hispanic communities in the US. Moreover, certain data constraints, such as the limited Instagram data accessible through the Facebook-owned social listening platform CrowdTangle, as well as the removal and disappearance of tweets including all available data, means that we might have missed important posts in our data collection.

To counterbalance this imperfect methodology, we focused a portion of First Draft’s collective daily monitoring efforts on vaccine-related conversations pertaining to Hispanic communities on social media. By tracking vaccine-related discussions in real time (a dynamic approach), we were able to identify, among other things, accounts influencing vaccine-related conversations in Hispanic spaces on social media, the ways in which these narratives were interpreted, how they were spread and the consistency or lack of moderation by social media platforms in violation of their own policies.

The key findings in this report are based on this mixed-methods approach, where both the static and dynamic approaches fed off and supported each other. Our research is based on online conversations. It’s important to remember that prominent posts online might not be as salient or even have the same framing in conversations that are occurring on the ground within these same communities. When designing policy or communications strategies, our findings should be paired with focus groups, surveys or other forms of qualitative research involving different members and representatives of the Hispanic community.

Below we offer more details on the methods used for both the static and dynamic approaches to our research.

Static data analysis:

We collected the top 100 most interacted-with posts from four separate entities — unverified Facebook Pages, Facebook Groups, Instagram accounts and Twitter accounts — between November 9, 2020, and September 9, 2021. The final dataset consisted of 400 total posts (100 posts per entity in both Spanish and English). WhatsApp is a highly used and important communication space for many Hispanic people in the US [70]. Observing the many vaccine-related conversations occurring on this closed messaging service would be of vital use to anyone trying to understand how vaccines are being framed in Hispanic communities. However, privacy concerns combined with the difficult nature of monitoring the messaging service prevented us from including WhatsApp data in this report.

We chose to work with unverified accounts as we wanted to best capture the individual voices and conversations occurring under the surface. The most interacted-with posts from verified accounts are often from large media organizations and don’t necessarily reflect the voices and conversations happening on social media around vaccines. Posts from Facebook and Instagram were collected by querying CrowdTangle’s API for posts containing different combinations of keywords relating to vaccines and Hispanic people. For Twitter data, we used Twitter’s Streaming API with the same combination of keywords. To avoid false positives, we conducted a secondary layer of filtering, using more specific keyword combinations to isolate vaccine-related posts related to Hispanic communities.

We also used a more general set of vaccine terms to identify Covid-19 vaccine-related posts in Spanish. We excluded posts focusing on the internal vaccine policies and politics of non-US countries as well as posts attacking non-US governments for their mishandling of Covid-19 vaccination distribution. We instead filtered for vaccine posts that captured a general sentiment (both positive or negative) related to Covid-19 vaccines.

With this final dataset, we borrowed Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke’s methodology for thematic analysis to code and identify key narratives and topics that emerged from the dataset [71]. This consisted of:

- Familiarizing ourselves with the data

- Manually coding the data

- Generating initial narratives

- Reviewing the narratives

- Defining and naming the narratives

- Writing up the results

Dynamic data analysis:

We identified Hispanic influencers who frequently produced anti-vaccine content and monitored and mapped anti-vaccine narratives emanating from these accounts. Influencers were found by conducting targeted Boolean searches on Tweetdeck and CrowdTangle. They were also sourced by following a news or popular culture topic around vaccines and identifying those accounts with significant followings that were perpetuating common misleading claims, such as the false narrative that Covid-19 vaccines are experimental, rushed and unsafe.

We identified other influencers on Telegram who hosted popular groups and channels. We traced users we found on Telegram spreading vaccine misinformation to their accounts on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. Influencers were selected based on the frequency with which they produced anti-vaccine content, the number of followers they had, and the engagement that these accounts received for their posts. We also monitored Hispanic and Spanish-language spaces on WhatsApp.

Two researchers, who consumed and monitored content in Hispanic spaces each day, employed different ethnographic techniques to analyze posts from the influencers and lists of accounts identified as being relevant to the vaccine discourse surrounding Hispanic communities. The researchers cross-referenced their results with findings from the static analysis to finalize the list of key narratives.

Topics, Narratives and Misinformation

To understand vaccine discourse on social media, it isn’t enough to monitor and verify individual pieces of content. We have to understand that individual pieces of content create larger attitude- shaping narratives. And these narratives fall into even larger, overarching topics that steer conversations and allow us to make sense of vaccine-related information on social media.

In a previous piece of First Draft research — Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation and data deficits on social media — we identified dominant vaccine narratives and topics on social media platforms in English-, French- and Spanish-speaking communities that could erode public trust in Covid-19 vaccines, and vaccines more generally [72].

The resulting taxonomy we created is useful in categorizing general vaccine-related posts and is currently being leveraged to build machine learning models to automatically classify vaccine content on social media. Yet as we showed in our recent report Covid-19 vaccine misinformation and narratives surrounding Black communities on social media, it’s unclear how valuable that taxonomy is when making sense of demographic-specific vaccine-related conversations on social media [73].

Different communities face specific issues whose historical and modern underpinnings are different from the general population. Furthermore, vaccine conversations surrounding Hispanic communities on social media — happening mostly in Spanish — employ a large degree of sarcasm and satire compared to other languages. Using the current taxonomy for vaccine conversations related to Hispanic communities on social media, for example, has the potential to miss important nuances and signals on social media, hampering efforts to make sense of these conversations online and possibly misrepresenting these communities altogether.

To better understand the narratives we surfaced and their position not only in vaccine discourse but in the greater political discourse in the US, we made an initial attempt to classify these narratives under previous topics as well as new topics that emerged with our analysis. It’s important to note that these topics are far from exhaustive. More research involving significantly more data will be needed to approximate anything akin to an exhaustive vaccine taxonomy for Hispanic communities. And even then, new issues will likely emerge, requiring the addition of topics.

Below we present the narratives and their topics, with an explainer for each topic.

Safety, Efficacy and Necessity

The topic of Safety, Efficacy and Necessity includes narratives concerning the safety and efficacy of vaccines, including how they may not be safe or effective. Narratives related to the perceived necessity of vaccines also fall under this topic.

It’s important to remember that having concerns about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines doesn’t mean a person is an anti-vaccination activist. Being vaccine hesitant is very different from being “anti-vaxx” and conflating vaccine-hesitant individuals with “anti-vaxxers” can result in stigmatization and may push people away from vaccines [74]. For many individuals in the Hispanic community, concerns around the safety of Covid-19 vaccines are real, often rooted in the history of medical racism and experimentation as well as the lack of quality health information in Spanish [75][76]. Fear, anxiety and mistrust make people especially susceptible to negative content and misinformation [77][78]. Given these fears, it’s unsurprising that most of the narratives we identified in our data fall under the topic of Safety, Efficacy and Necessity.

Below we take a look at the most salient narratives that emerged from our data under this topic.

Narrative that the Covid-19 vaccine is experimental, rushed and unsafe

Ever since Covid-19 vaccines began to be rolled out in the United States in December 2020, anti-vaccine sources have weaponized the “emergency use” authorization granted to these vaccines to push the misleading narrative that Covid-19 immunization campaigns are akin to mass experiments. Exacerbated by extant mistrust in health authorities as well as concern about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines among certain Hispanic communities, the idea that the Covid-19 vaccine is experimental, rushed and unsafe continues to spread in Hispanic spaces on social media.

Screenshot by authors

The narrative is supported by numerous false or unsubstantiated claims, such as the idea that the mRNA technology used in some of the Covid-19 vaccines is novel and untested and, as a result, unsafe. Similar uncorroborated posts claim that there is not enough data to prove the long-term safety of Covid-19 vaccines and that those who have been inoculated will eventually die from the vaccine.

Screenshot by authors

Other spurious content on social media supporting this narrative falsely claims that the mRNA technology used in the vaccines will cause permanent changes in your genes and DNA. According to these unfounded posts, because the vaccine will permanently change the recipient’s DNA, these effects will become hereditary and will affect any offspring. The posts falsely state that Bill Gates is the architect of these vaccines, and his goal is to control the world’s population by keeping it in fear of getting sick and blaming those who do not get inoculated for the resulting outbreaks.

Given the continued safety concerns around Covid-19 vaccines among some Hispanic people and the history of sterilization targeted toward various Hispanic communities, this narrative and the false claims underpinning it have the potential to discourage people from seeking out the vaccine.

Narrative that Covid-19 vaccines cause severe adverse reactions and are dangerous

This narrative continues to play into concerns about the safety of vaccines. Because the narrative is based on a kernel of truth, it is particularly convincing to those already fearful of vaccines. Some people do experience severe adverse reactions to some Covid-19 vaccines, but these incidents are incredibly rare [79][80[81]. Moreover, much of the online content supporting this narrative comes packaged in video- or image-based formats and is highly emotionally charged, making this misinformation especially convincing [82][83].

Unverified videos from Mexico, Argentina and the US showing vaccine recipients purportedly fainting and convulsing have been used to evidence the danger of Covid-19 vaccines, despite some of these patients fainting because of their fear of needles [84].

Screenshot by authors

Other videos, which spread rapidly in Spanish-language spaces on social media, falsely claimed that the Covid-19 vaccine had made them magnetic. Other posts falsely claimed that the Covid-19 vaccines would turn people into controllable zombies.

Screenshot by authors

Other posts falsely asserted that Covid-19 vaccines will turn men gay. Hispanic communities are not exempt from male chauvinism and homophobia, which contribute to the stigmatizaiton and rejection of gay men [85]. As a consequence, the fear of turning gay for many men still subscribing to these ideals has the potential to discourage them from getting a vaccine when confronted with this kind of misinformation.

Narratives that Covid-19 vaccines are especially dangerous to reproductive health

Despite the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention saying that vaccine shedding does not occur in any of the Covid-19 vaccines administered in the US, false claims pushing the idea continue to proliferate within Hispanic spaces on social media [86]. These claims have appeared within various videos on alternative video hosting services, such as Rumble, where they are subtitled in Spanish and hosted on Spanish-language alternative medicine and natural health websites.

Often, “shedding” claims are coupled with other false claims linking Covid-19 vaccines to infertility. These false infertility assertions have been used to advance depopulation narratives, which, given the history of sterilization in Hispanic communities in the US and US territories, has the potential to turn some people away from Covid-19 vaccines.

Screenshot by authors

Other posts on social media link Covid-19 vaccines to irregular menstrual cycles and bleeding. These claims are also being used to support the idea that Covid-19 vaccines could result in infertility. It’s unclear whether there is any causal relationship between Covid-19 vaccines and reports of menstrual irregularities [87]. This lack of clarity prompted the National Institutes of Health to sponsor grants to multiple universities in the US to explore any possible connection between menstrual changes and Covid-19 vaccines [88]. Nonetheless, the continued data deficit will likely provide space for more mis- and disinformation to emerge around the issue [89].

Narratives claiming Covid-19 vaccines contain poisonous compounds

Many posts surrounding Hispanic communities on social media claim that Covid-19 vaccines contain composite ingredients such as GMOs, graphene, mercury and aluminum, feeding fears about the safety of the vaccine as well as depopulation efforts. Posts peddling these false claims have made their way across many spaces in Latin America as well as Hispanic spaces on social media in the US.

Screenshot by authors

Throughout the pandemic, wellness influencers and “natural medicine” accounts have misleadingly supported the idea within Hispanic spaces on social media that a healthy immune system — bolstered through one of myriad supplements and vitamins championed by these entities — is more effective than vaccines at protecting you from Covid-19. Many of these accounts push anti-vaccination posts with misleading claims, such as that Covid-19 vaccines contain “unnatural” ingredients, as reasons not to get the vaccine.

Given the large followings of many of these influencers and ways in which Covid-19 vaccine misinformation can be monetized — many social media accounts peddling anti-vaccine sentiment and “alternative medicine” direct users to websites where they can buy unproven supplements and dubious treatments for Covid-19 — it’s likely that this narrative will persist not only around Covid-19 vaccines, but also vaccines more generally.

Getting the Covid-19 vaccine is more dangerous for children than not getting one

Linked to the narrative that vaccines are ineffective and unnecessary is the idea that getting Covid-19 vaccines is more dangerous for children than not getting them. Many posts supporting this narrative claim that children are less likely to develop severe symptoms of Covid-19 compared with adults and as a result vaccines aren’t necessary for them. However, the Delta variant highlighted how children are vulnerable to developing Covid-19, including severe cases of the disease [90].

Misreporting about a supposed imminent outbreak of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) has fueled conspiracy theories in Hispanic spaces on social media supporting the idea that Covid-19 vaccinations are dangerous for children. Many posts on social media have made unsubstantiated claims that an outbreak of polio will occur at the same time Covid-19 vaccines are approved for younger children.

Screenshot by authors

Claims of an AFM outbreak originated from an August 19 report from Asian News International that erroneously reported a 2020 outbreak warning from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a 2021 alert, according to FactCheck.org [91]. But the claim has taken on a life of its own, implicating Covid-19 vaccines and making its way through Hispanic communities on social media.

Other posts supporting the idea that Covid-19 vaccines are more dangerous for children than not getting one point to young adults developing myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) after receiving a Covid-19 vaccine. Misreporting has amplified these claims and many social media posts exaggerate the danger of children developing myocarditis to support the idea that Covid-19 vaccines shouldn’t be given to this demographic. While it’s true that myocarditis can occur in children post-vaccination, it’s much more common for the condition to emerge from having had Covid-19 [92].

As children return to school and Covid-19 vaccinations become approved for younger cohorts of children, this misleading narrative is likely to gain more momentum. Emotive videos and images purportedly showing children having adverse reactions to Covid-19 shots will likely appear more frequently on social media — a common tactic used by anti-vaccination activists to instill fear around childhood inoculation. Hispanic children have already suffered disproportionately from Covid-19 compared to white children, both in terms of health and education, and this kind of content could widen that divide.

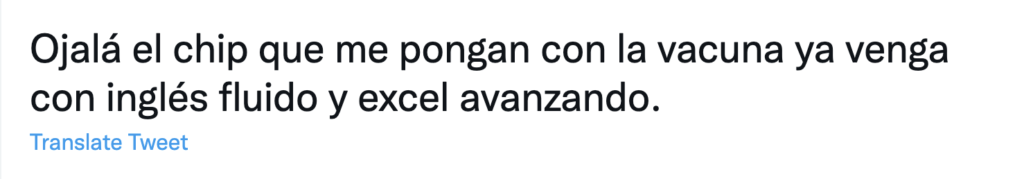

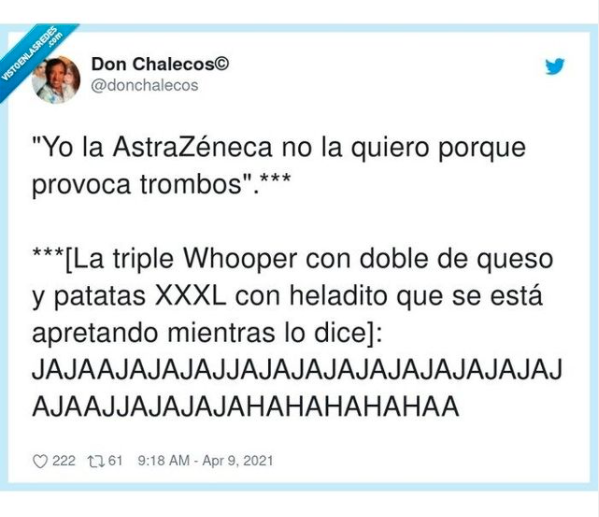

Narratives poking fun at people who are not vaccinated

Parody and satire featured heavily in Hispanic spaces on social media platforms by way of memes, videos or text-only jokes. Some of the most pervasive messaging that surfaced from our data poked fun at individuals refusing to get vaccinated or who believed in the many conspiracy theories surrounding Covid-19 vaccines.

Screenshot by authors

Many of these messages ridiculed the hypocrisy of individuals who said they didn’t trust the vaccine or claimed it contained harmful or unnatural ingredients but who would then trust unreliable sources or consume dangerous and unnatural substances in some other setting.

Screenshot by authors

Other posts ridiculed the logic of individuals who were initially keen to get vaccinated but then decided not to get a Covid-19 vaccination because they had been exposed to misinformation.

Screenshot by authors

These posts were seemingly intended to challenge the false logic and reasoning of those who refuse to get a vaccine. Yet it’s still unclear how effective humor and satire are in creating attitudinal changes [93][94].

Screenshot by authors

And it’s even less clear whether humor is useful in correcting misinformation. Humor is effective in capturing audiences’ attention around a specific issue and has, in some instances, been found to effectively communicate vaccine information [95][96]. But the message behind a joke or piece of satire is rarely universally agreed upon [97][98]. For example, a satirical post that for one audience is clearly criticizing a politician may be interpreted as an endorsement by that politician’s supporters [99].

The politicization of Covid-19 has meant that Covid-19 vaccines, including individuals’ willingness to get vaccinated, have become an issue of identity [100][101]. As such, vaccine skeptics who read satirical or humorous posts lampooning them may interpret these posts as an attack on their identity, which could further entrench and solidify their vaccine resistance [102][103]. Furthermore, in an attempt to humorously correct popular misinformation, many of these satirical posts may actually be giving more oxygen to conspiracy theories, rumors and anti-vaccine narratives, which could potentially further erode trust in vaccination efforts [104].

Given the heavy use of humor, sarcasm and satire surrounding Hispanic communities on social media, more research should be undertaken to better understand the effects (positive or negative) that result from these kinds of vaccine posts as well as the potential role of humor in communicating information around vaccines [105].

Natural language processing techniques and sentiment analysis continue to develop rapidly. Yet most models cannot accurately detect and classify sarcastic and satirical posts [106]. The subtle use of sarcasm and satire in Spanish-language vaccine-related posts combined with the pervasiveness of these kinds of posts will complicate efforts at automatically classifying vaccine-related posts in Spanish.

Furthermore, not only does the type of humor vary by culture — humor in Spain is different from humor in Mexico, for example — but so does the language and slang used to convey this humor. Attempts at understanding vaccine discourse and prominent narratives using such classifiers have the potential to grossly misrepresent the key vaccine-related issues facing Hispanic communities.

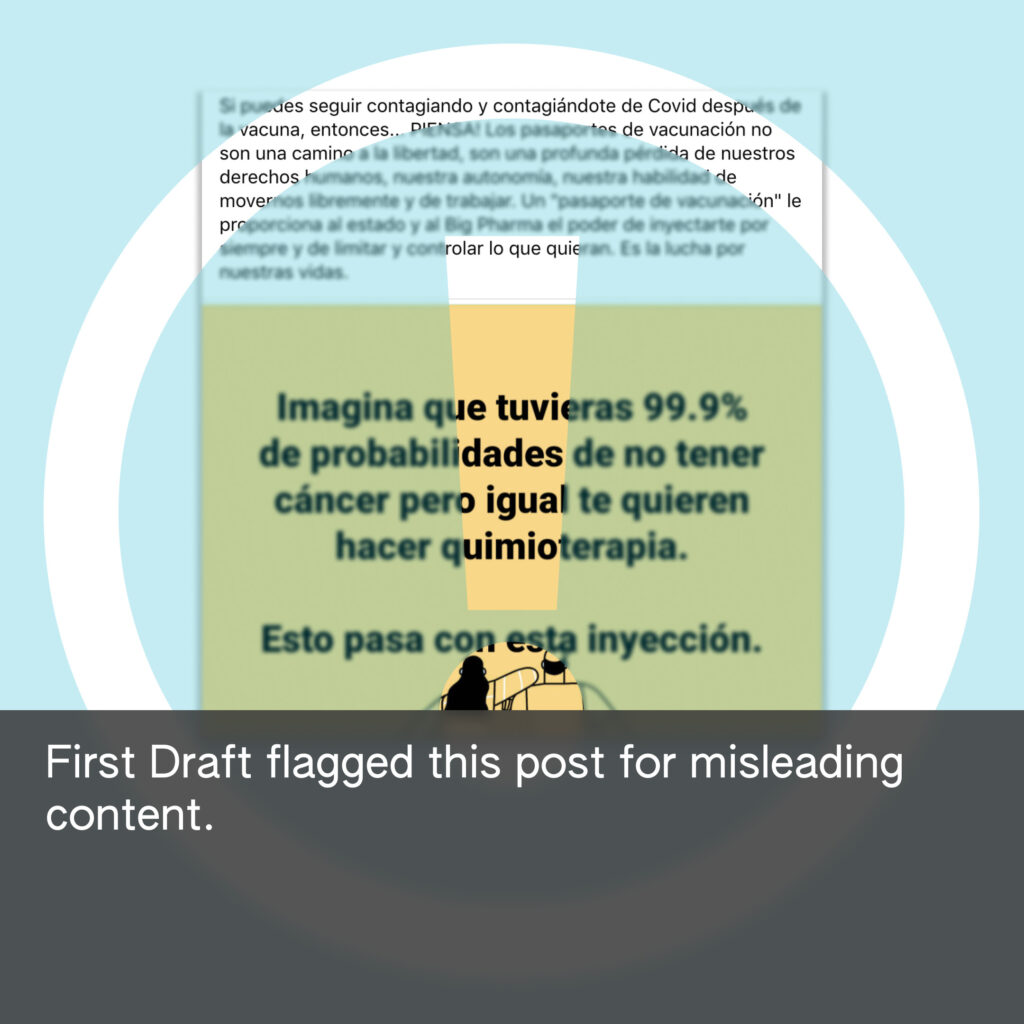

Conspiracy Theory and Liberty/Freedom

Narratives falling under the topic of Conspiracy Theory contain or concern well-established or novel conspiracy theories involving Covid-19 vaccines [107]. In crisis situations, such as the pandemic, conspiracy theories can emerge from data deficits or situations of uncertainty in which people try to make sense of their reality by grabbing onto different threads of information, whether true or false [108]. Even before the rollout of the Covid-19 vaccine in the US, conspiracy theories relating to the vaccine, such as the idea that vaccines contain microchips that will be used to control the population, played an outsized role on social media [109].

The topic of Liberty/Freedom concerns how vaccines may affect civil liberties and personal freedom. Narratives before the rollout of vaccines falling under this topic included the idea that “it starts with a mask, moves to vaccines and ends in total control” as well as the misleading notion that mandatory vaccines would “railroad our rights” and freedoms.

As the pandemic progressed and vaccines were rolled out, we noticed that many narratives falling under the topic of either Conspiracy theory or Liberty/Freedom were not mutually exclusive. Often, vaccine-related narratives that fell under Liberty/Freedom were made up of posts that also contained elements linked to established conspiracy theories.

Below we take a look at one such narrative that emerged from our data, which could fall under both topics.

Narratives claiming Covid-19 vaccines will be used to control the population

Accounts posting content supportive of this narrative often employ “vaccine passports” or vaccine mandates to either advance 1) the idea that they will be used to establish a global regime of total surveillance or 2) arguments attacking politicians and political parties seen as curbing individuals’ “freedom” through their use of these mandates [110].

Screenshot by author

For example, many posts in Hispanic spaces on social media falsely claim that “vaccine passports” are related to the ID2020 agenda, a conspiracy theory that claims Bill Gates is behind a coalition with plans to cement a global surveillance state by taking advantage of conditions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic [111]. Although these narratives generally revolve around claims of microchips, vaccine passports and mandates are implicitly linked to this plan. Social media platforms seem to have improved somewhat in moderating misinformation related to Gates, but conspiracy theories linking him to Covid-19 vaccines still surface in Spanish-speaking spaces on social media.

Other posts make unsubstantiated claims that the US government is working with “big tech” to assert control over people by implementing “vaccine passports.” These posts falsely compare the US to Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and modern-day China with its social credit system. Some posts go as far as claiming that vaccine mandates will be used to prevent people from buying firearms, registering a vehicle or taking out a loan as part of an effort to combat domestic extremism in the US.

Screenshot by authors

These arguments are often promoted by right-wing groups and politicians. Republicans in particular have been accused of leveraging the idea that vaccine passports and mandates are a looming encroachment on individual rights by the government to open a new front in the “pandemic culture wars” [112].

Screenshot by authors

It’s important to remember that Hispanic people in the US are not a monolithic group, especially along party lines. For example, the majority of Cuban-Americans vote Republican, as do many Venezuelan-Americans and Nicaraguan-Americans [113][114]. Narratives falsely equating vaccine mandates to a “communist” totalitarian state and President Joe Biden to a radical socialist à la Hugo Chavez have the potential to influence the decision-making around Covid-19 vaccines for many Hispanic people [115][116]. And as vaccine mandates are rolled out more widely across the US, these false narratives are likely to spread.

Versions of this narrative emphasizing a surveillance state also have the potential to discourage undocumented Hispanics residing in the US from making use of vaccination sites, as it plays into pre-existing fears about immigration authorities and deportation.

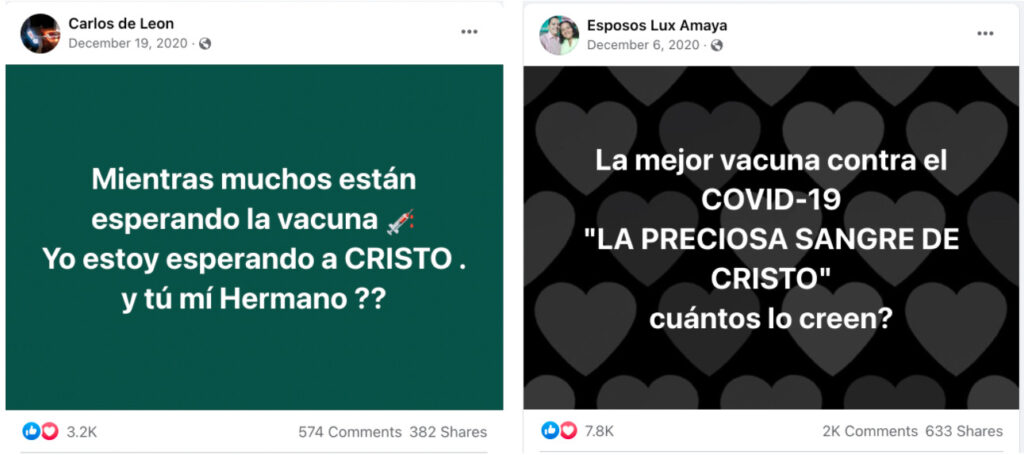

Religion

The topic of religion includes both narratives that Christ is the only protection needed against Covid-19 and that the vaccine is the “mark of the beast.” This was one of the most significant topics among Facebook Groups in particular, comprising 18 per cent of posts in the dataset.

Data from the Public Religion Research Institute shows that among religious groups in the United States, Hispanic Protestants tie with white evangelical Protestants as the least likely to accept vaccines (56 per cent). It’s important to note that religion among Hispanics is not monolithic, with large differences between Protestants and Catholics. Vaccine acceptance among Hispanic Catholics was 80 per cent in June [117].

Last year saw the rise of Mexican pastor Oscar Gutierrez, who amassed over 200,000 followers in the first three months of creating his Facebook Page. His videos promoting chlorine dioxide solution as an alternative treatment to Covid-19 received millions of views before they were taken down by Facebook.

The trusted position of these religious leaders has the potential to legitimize dangerous alternative treatments, but it also presents an opportunity for increasing vaccine uptake. 44 per cent of vaccine-hesitant Hispanic Protestants say faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated [118].

Narratives that the best vaccine against Covid-19 is the “blood of Christ”

A very common religious narrative is that vaccines are unnecessary because the only protection needed for Covid-19 is the blood and salvation of Jesus Christ. These kinds of posts were especially common on Facebook Groups. While their message is simple, many of them racked up thousands of likes and comments in support.

Screenshots by authors

Narratives that vaccines are the mark of the beast

Claims that vaccines are the “mark of the beast” or “the platform of the Antichrist” often come with concerns about abortion or invoke conspiratorial language about microchips and population control.

As early as June 2020, Spanish Cardinal Antonio Cañizares Llovera said in a filmed Mass shared around the world that attempts to find a vaccine were the “work of the devil” and would involve “aborted fetuses” [119].

On Instagram, pastor couple Miguel and María Paula Arrázola in Cartagena, Colombia, shared a broadcast with their 394,000 Instagram followers in which their guest Ruddy Gracia, another evangelical pastor, said that behind the compulsory vaccine there is a chip made by Gates. “That is the beginning of the platform of the Antichrist, how he will bring about the mark of 666 and will result in you not being able to get a passport, travel, have a license, buy or sell without that chip.”

In a more recent example, Evangelista Gary Lee Katzelnik posted videos to his Facebook page suggesting the vaccine was the mark of the beast. Each received more than 240,000 views.

Screenshot by authors

Alternative Treatments

Alternative treatments for Covid-19, which have been very popular in Latin America, also play a major role in diaspora conversations. Latinxs in general have a propensity toward medical pluralism, seeking out treatments within and outside conventional allopathic medicine [120][121]. A history of traditional medicine, home remedies and the use of family members as sources of health information alongside — or even before — consulting a medical physician is common, which makes this group even more vulnerable to misinformation about alternatives to vaccination [122].

These treatments range from harmless homemade remedies such as teas and baking soda drinks, to more potentially dangerous substances, such as chlorine dioxide solution and over-the-counter and prescription medications including ivermectin, dexamethasone, zinc and hydroxychloroquine.

Some of these alternative treatments were catapulted into popularity by their backing from major religious leaders in the Hispanic community who grew their online presence during lockdowns.

In many cases, though, the cultural infrastructure for popularizing these treatments existed long before the rollout of vaccines. Chlorine dioxide solution, for example, was used as a “cure” for autism [123][124]. Ivermectin, which is more accessible in Latin America as an affordable, over-the-counter anti-parasitic, was used in Hispanic communities before the wider anti-vaccination movement began promoting it [125]. And a robust ecosystem of media and products for “alternative” and “holistic” health in the US has long promoted misleading health information as a basis for increasing market demand [126]. These narratives often play into fears about corruption and “Big Pharma,” some of which have roots in legitimate questions about vaccine development and some of which do not.

Below we take a look at some of the most popular alternative treatments that emerged in our research.

Chlorine Dioxide Solution (“CDS” or “MMS”)

Chlorine dioxide solution, also known as CDS or “miracle mineral solution” (MMS), is an industrial bleach that has been promoted as a cure and preventative treatment for Covid-19. Several organizations have warned against the use of CDS to prevent Covid-19, including the US Food and Drug Administration and the Pan American Health Organization [127][128].

In July 2020, Mexican pastor Oscar Gutierrez broadcast one of the most-watched videos about the substance on Facebook, racking up more than 2 million views before the platform labeled it false information and took it down. Gutierrez in turn popularized the work of Andreas Kalcker, an anti-vaccination advocate who claims to be a German scientist and who has also promoted bottles of CDS in his Facebook broadcasts [129].

Screenshot by authors

One of the organizations that has helped promote CDS in Spanish-speaking communities on social media is Coalición Mundial Salud y Vida, also known as Comusav. Comusav has 15 delegations throughout Latin America and Spain, and some of its affiliated Facebook Pages had tens of thousands of followers. Facebook has shut down Facebook Groups and Pages affiliated with Comusav promoting CDS in the past, but a number of them are still online [130].

Promotion of CDS can also be found on messaging apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp. In February, a Telegram channel that advocates for the use of chlorine dioxide (MMS) as a cure for Covid-19 shared a video interview of Kalcker in which he advocates for its use. The video has been viewed 19,500 times.

Home remedies

Teas, ginger drinks and other homemade remedies have also been a large part of the discourse on alternative treatments.

One of the most common examples of this were claims that Covid-19 could be fought by gargling a mix of aspirin, lemon and honey. Videos promoting this treatment received thousands of views and shares, some of which were removed by Facebook.

Screenshot by authors

Baking soda, lime and vinegar was another popular iteration of this claim. Here are two examples of a post that went viral on both Facebook and closed messaging platforms such as WhatsApp.

Screenshot by authors

Posts also surfaced on Facebook claiming moringa tea, a traditional remedy brewed from parts of the moringa or drumstick tree, is a cure or viable treatment for Covid-19. These claims have their origin in photos that surfaced on Facebook of officers from the Colombian National Penitentiary and Prison Institute preparing tea in a large pot.

One of the most popular images of this treatment online shows what appears to be an officer holding a cup of the concoction containing moringa, eucalyptus, lemon and panela, an unrefined whole cane sugar. The story garnered even more attention on August 14 when Noticias Caracol covered the goings-on in Modelo Prison in Barranquilla, Colombia. The piece does say there is a lack of scientific backing for the use of moringa, but it shows officers drinking the moringa tea. It has over 235,000 views.

Screenshot by authors

As with CDS, Facebook users have also begun using the platform to promote the sale of moringa tea. Since August 14, several unverified Facebook users have posted personal ads where they claim moringa can be used to treat Covid-19.

Conclusion

When considering Hispanic communities, there is a great need to account for the diverse experiences that Hispanic or Latinx can encompass. Failing to acknowledge these differences by employing reductionist and one-size-fits-all notions of Hispanics risks ignoring the most vulnerable populations and failing to understand the true impact of information disorder.