By Pedro Burgos, professor at Insper, ICFJ Knight Fellow

If one message could represent all the misinformation that circulated on WhatsApp during the 2018 presidential election season in Brazil, it would be something like this: a real picture of electronic ballot boxes, presented out of context, denouncing electoral fraud meant to harm then-candidate, now-President Jair Bolsonaro. That image would be coupled with a short text mixing real and false misdoings from the opponent’s party, urging everyone to share it wildly.

The October 2018 elections in Brazil, the largest democracy in the Global South, saw Bolsonaro win the presidency after defeating Workers’ Party candidate Fernando Haddad. In an increasingly polarized environment, 24 newsrooms in Brazil came together to report on mis- and disinformation in the collaborative journalism project, Comprova, supported by First Draft.

WhatsApp is a major player in Brazil: an estimated 120 million people were using the platform by May 2017. Comprova set up a central tipline on WhatsApp for Brazilians to submit tips for Comprova to investigate through its application program interface (API), a first for the platform to give such access to an NGO. Due to WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption, this method of soliciting tips is the only possible way to collect misinformation data without violating the app’s terms of service.

During the 12-week project, the WhatsApp tipline received 105,078 messages from the audience, including suspicious claims, images, videos, or audio messages for the team to verify and investigate. It’s one of the largest data sets of WhatsApp messages to electoral campaigns.

- Read the Comprova Summary Report (PDF)

- Read the Comprova Full Report (PDF)

What we collected

Data collection was possible through Zendesk, a customer service platform that interacts and collects messages from WhatsApp. All messages sent to Comprova’s WhatsApp phone number were routed through Zendesk, and because this service has an API, we were able to collect structured data, as well as download the 87.6 GB of attachments, among other benefits and some drawbacks.

This data came from an overall data set of 242,124 messages that were received or sent during the project. Many of these were welcome messages or replies where Comprova journalists asked for more information to help with the verification process. To evaluate a clean corpus of data, these additional messages were removed from this analysis.

What we found

- Misinformation takes many formats on WhatsApp

Together with data reporter Bernardo Vianna, we were able to sort messages by type and, using various computing techniques, group similar images, audio and video files.

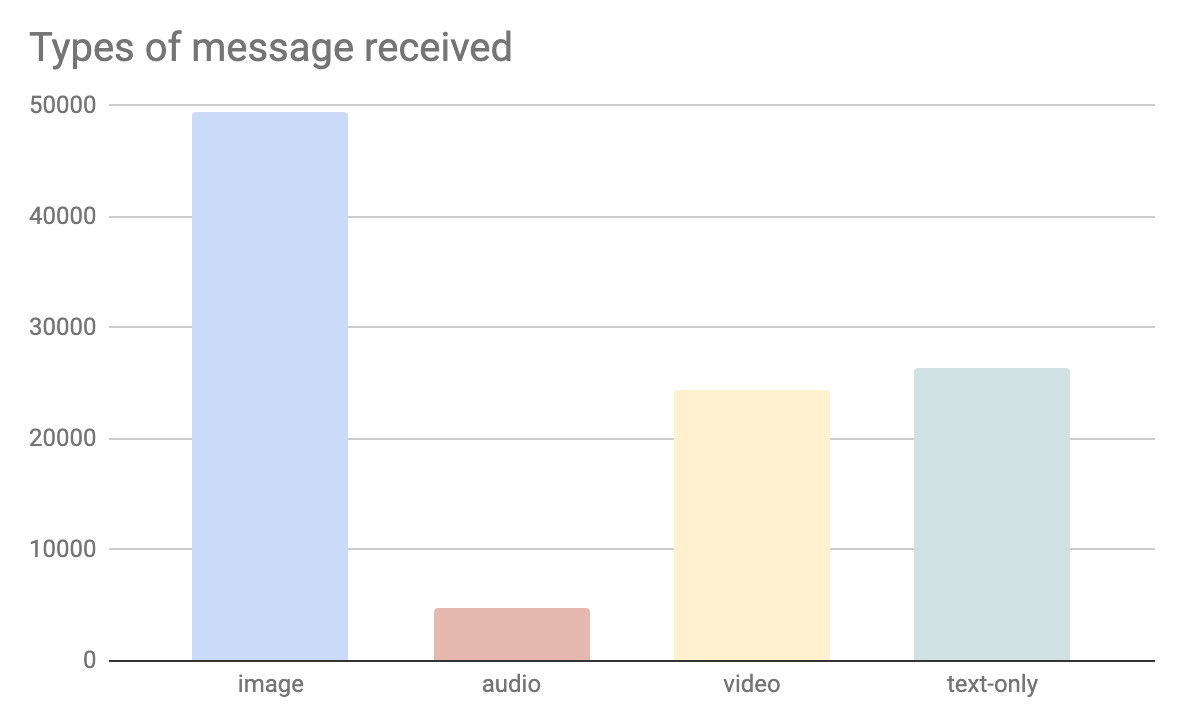

Types of Whatsapp messages received

A large portion of messages forwarded to Comprova were image files, usually real pictures with partisan captions. Official documents or real news stories taken out of context and screenshots (of both real and false conversations) were also popular.

Classic memes with a big text overlay were less common in Comprova’s database, possibly because as propaganda or humorous pieces they don’t purport to be true, so are less debunkable.

Research from Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) showed a similar pattern in terms of themes. Its research used a different methodology, collecting data from open WhatsApp groups where short links were available via Google. By contrast, Comprova relied on data submitted to us, because of issues around consent.

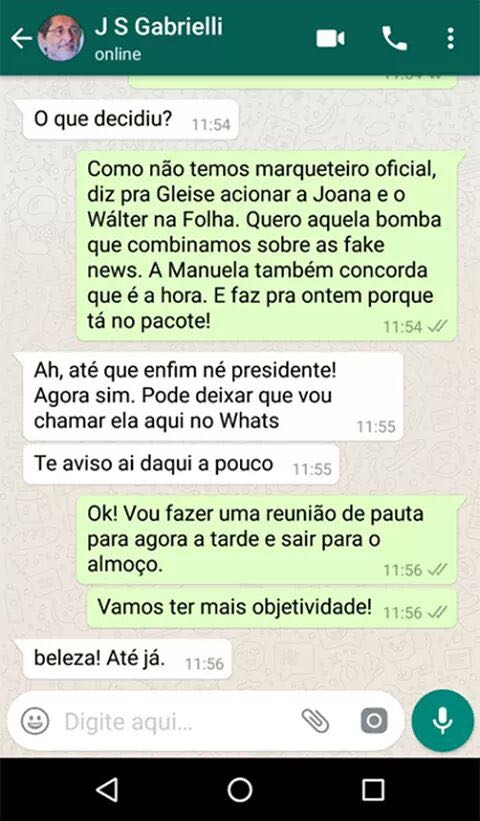

This screenshot, shared 663 times, shows a false conversation between former Petrobras President Jose Sergio Gabrielli and Fernando Haddad, coordinating attacks on Bolsonaro together with Folha, one of Brazil’s largest newspapers. In one version of this hoax, the same picture of a check is put forth as proof that Haddad’s campaign was paying the media to go after Bolsonaro.

Some of the images were sent in bulk, like the “album” of official pictures of Workers’ Party members meeting with OEA (Organization of American States) electoral observation missions. The accompanying text alleged that the meeting was secret, with the goal of rigging the results in favor of Haddad. Comprova’s report found the claims false and misleading.

- The most viral messages were from Jair Bolsonaro supporters about the integrity of the elections

Comprova’s WhatsApp tipline received the same themes in different media forms. While there were personal attacks, particularly against Fernando Haddad, the most viral messages were from Bolsonaro’s voters worried about, and creating stories around, the integrity of the elections.

Brazilians love to send audio messages, and there were a number of viral audio files among the disinformation sample: 30 were sent to Comprova an accumulated 1,642 times, or 33% of the total. Allegations of electoral fraud accounted for two-thirds of the most viral audio messages. The most widely shared audio was a version of a video where two police officers talked about electoral ballots being violated. Those officers are currently under investigation.

While pro-Bolsonaro messages dominated the sample Comprova collected, four of the most popular audio recordings—including the second most shared, sent 208 times—were variations of a conspiracy theory claiming that the stabbing of Bolsonaro was staged.

Text-based messages followed the same themes, with an emphasis on the claim that electoral fraud took Bolsonaro’s win in the first round. Many of the messages that were sent repeatedly to Comprova used the tactics of mid-1990s chain emails.

The most widely shared text, received 541 times with the same words, claimed that the number of absentee ballots and null voting were inflated by the electoral authority, and ended “if you send this message to just 20 contacts in a minute, Brazil will unmask this criminal. DO NOT break this chain. The unwary must know the truth.”

A real picture of a criminal gang apprehended by police was shared with a message alleging—with no basis—that the criminals would use stolen money to fund Haddad’s campaign.

There had been a lot of press coverage about the “culture wars” around the election. A few of Bolsonaro’s supporters infamously attributed to Haddad the distribution of “erotic baby bottles” to children. But if these messages really went viral, they didn’t arrive at Comprova’s WhatsApp number in large quantities.

Nothing related to gender issues, abortion, or gun laws appeared in the top 200 images shared. We also ran Google Cloud Vision in every image to extract “entities” (be it a candidate, a symbol, or an object), and there weren’t large numbers related to “culture wars” issues.

You might be able to infer that Comprova’s tippers were therefore discerning enough that they wouldn’t think this type of information should be taken seriously, or that these types of messages were contained in filter bubbles.

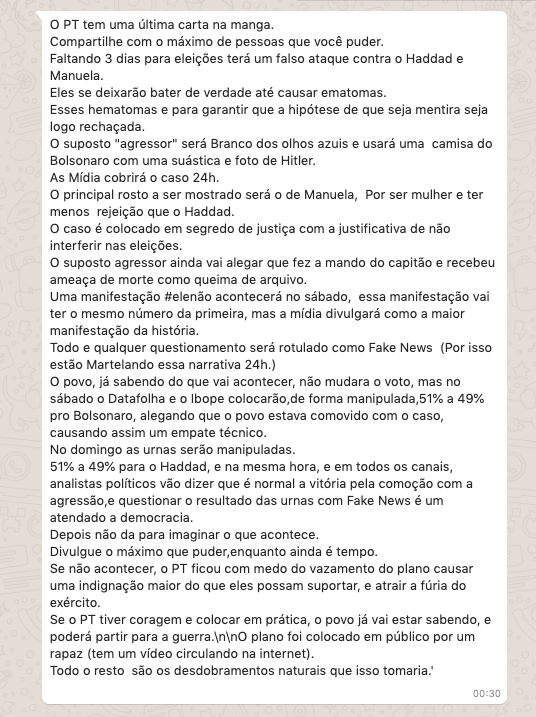

This viral message claimed that Haddad and his running mate, Manuela D’Ávila, would stage themselves being beaten up by actors wearing Bolsonaro’s T-shirts and swastika. It was shared to Comprova’s WhatsApp number 217 times. The video with the same script was shared 445 times.

- WhatsApp was mostly a closed environment

The WhatsApp messages contained very few links to the wider web, which may be attributed to zero-rating plans in Brazil where telecom providers don’t count the use of certain apps or services like WhatsApp against consumers’ monthly data caps.

While the most common themes found their way outside WhatsApp in YouTube videos and Facebook posts, Comprova editors could not locate a number of conspiracy theories that tippers shared with them on the larger web, which made verification work more challenging.

Of course, there is still much to learn from the Comprova data, as we focused much of our findings in the fathead, not the longtail. Comprova will share our data with other researchers who are interested in this crucial moment in Brazil’s history. Please contact us using this form to request access to the Comprova data for your research.

To stay informed, become a First Draft subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.