With the amount of fake images, videos and hoax stories circulating on the web and social media, knowing the tools and techniques to verify such information has become a vital part of a journalist’s job.

There are no quick wins though. At this year’s International Journalism Festival, BuzzFeed Canada editor and founder of Emergent.info Craig Silverman and Josh Stearns, founder of Verification Junkie and director of journalism and sustainability at the Geraldine R Dodge Foundation shared their advice.

“Sometimes you do get a smoking gun but a lot of the time it’s pulling a bunch of different points together and looking at them together and seeing what the story tells you,” said Silverman.

They detailed some of their methods in four case studies.

Verifying images

Last year a major UK news organisation ran a story based on some photos from Russia, which claimed two women who worked at a department store had decided to frolic naked in the snow. They lost their jobs as a result, or so the story claimed.

“I wanted to figure out did this actually happen,” said Silverman, “because a lot of the time when something originates in one country or in one language and then crosses that language and geographical barrier things can get lost and messed up.

“So what do we need to do to figure this out?”

The first step was to reverse image search the photos, “which are at the core of this piece”, he said, to figure out if the videos had appeared online before and, if possible, find where they appeared first.

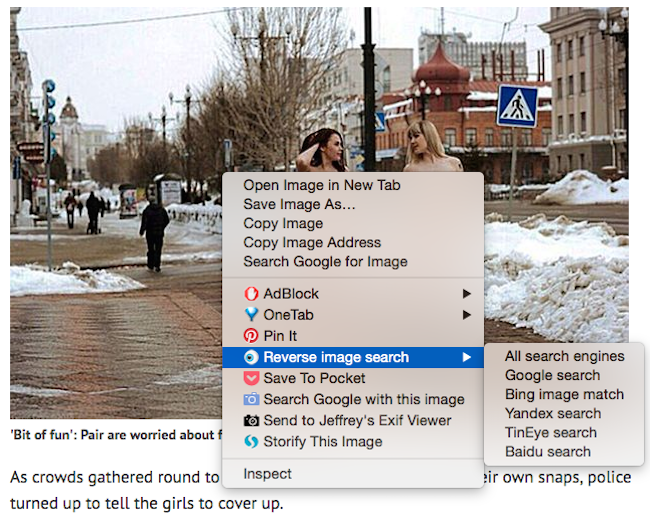

Silverman recommended the Chrome browser plug-in RevEye to search multiple databases for an image to see if it has appeared online before, and after conducting his search he found a Russian-language story using the same photos which was published a month before the English-language story.

How browser plug-in RevEye works for reverse image search. Screenshot from Mirror.co.uk, original image by Gene Oryx

After translating the Russian article, Silverman found no mention of the women losing their jobs or working in a department store, contrary to the English piece. It also named a different photographer, ‘Gene Oryx’.

“So we know there are some problems here and we need to figure out which is true,” he said.

Using another Chrome plug-in, Storyful Multisearch, Silverman was able to search Instagram, Spokeo, Tumblr, Twitter, Vine and YouTube for any mention of the two photographer’s names.

The only results for the name in the English-language story were related to the story, but the photographer in the Russian story had a history of similar photo shoots, and a standard search revealed a website and social media accounts.

The photographer confirmed the English story to be false via email and attached one of the original photographs, allowing Silverman to look at the Exif data to investigate when and where the image was captured.

“One caution I want to say about this is people can manipulate meta data,” Silverman said. “It’s not a foolproof thing.”

Nearly every social network strips out an image’s Exif data when it is uploaded, making finding the original and contacting the source all the more important when verifying images.

“So from the use of a few tools, all free, not a huge amount of time taken to do this, we can figure out there are a lot of problems with the [English-language] story.”

Verification steps

Reverse image search

Look for Exif Data

Look for names of sources in the story

Try to find the first use of the images/story about this

Verification tools

RevEye

Google Translate

Storyful MultiSearch

Google Search

Exif Viewer

Email

Verifying people

When a married couple killed 14 and injured 22 at the inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, California last December, news organisations were quick to cover the story and look for eyewitnesses.

But Twitter user @jewymarie, going by the name ‘Marie Christmas’, ‘Marie Parker’ or ‘Marie Port’ decided to trick their way into some coverage. Stearns described the red flags and suspicions which should have made journalists question the testimony.

“This supposed eyewitness only reports things that had already been reported in the press and there a couple of times when they walked back on things that they had said over the course of this.”

“So how did this happen and how can we avoid this happening in the future?”

Reporters first noticed the fake eyewitness through their claims on Twitter. But one of the first steps for any of the reporters checking out a source should have been to go back and look at previous tweets to see if they fit with the story, said Stearns.

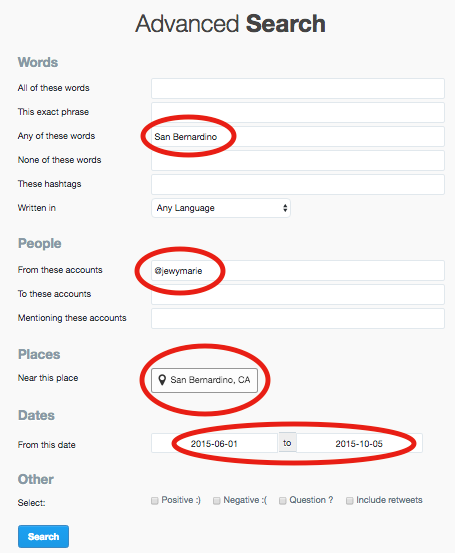

Twitter advanced search is a great tool for searching through an account’s old tweets, he said.

“You can look for San Bernardino, you can look for the account and look for geotags and set a date limit to the search so there are lots of ways to tweak the search to really drill down into this.”

Looking at a user’s “social footprint” is important too, checking their bio for any websites or other information, searching for their username on other networks, and looking at the followers and who they are following.

“MentionMapp allows you to see who the person is talking to and what they’re talking about, so it maps conversations and people,” he said.

Followerwonk is a useful tool for analysing a Twitter user’s followers by location, to better understand what communities they may be part of and if what they are claiming matches with their history.

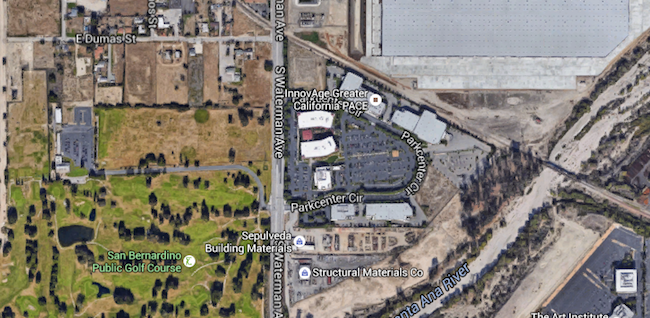

“In the [broadcast] clip ‘Marie Port’ couldn’t really describe the area,” said Stearns, but journalists can get to know the area they are covering using Google Maps or photo services like Flickr and Panoramio, even if they are on the other side of the world from the event.

A number of the fake eyewitnesses statements did not match with the geography of where the San Bernardino shooting took place, especially the claim they were hiding behind a building across the street.

A screenshot from Google Maps, with the Inland Regional Center in the middle. Witnessing the shooting from behind a building across the road is highly unlikely

“When you start to map it out the story they were giving wasn’t making sense,” said Stearns. “So you can get to know the area and get a sense for the story you’re hearing and how accurate it is.”

A lot of journalists tried to get ‘Marie POrt’ on the phone, however, but they claimed to not have a phone despite “tweeting constantly”, said Stearns, and claiming to be at the scene.

“A whole load of red flags came up throughout the course of this story and a lot of the times with verification you go with your gut,” he said, “and if you can’t get the kind of verification you need to run something in a story you may just need to wait.”

Steps

Look at past tweets

Check their bio and social footprint

Get to know the area

Pick up the phone

Trust your gut

Tools

Twitter Advanced Search

Mention Map

Followerwonk

Google Maps

Google Images and Flickr

Verifying video

In 2012, a dramatic video of a thunderstorm was uploaded to YouTube, in which lightning supposedly sparks a fireball in a woman’s backyard. Rare and dramatic weather moments are of natural public interest, but are also widely faked.

Storyful investigated the video at the time and Silverman broke down the process.

The original video was posted in 2012, and was later replaced when the licensing rights changed

The YouTube account which posted the video didn’t have a lot of history, said Silverman, although the name did seem like a real name. There weren’t many clues in the video itself either, she didn’t mention where she was and it was “just a very natural ‘holy shit’ moment. So what we have is really just the name.”

Spokeo is a great tool for searching for people’s contact details in the US, and the name Rita Krill returned results in New York, Pennsylvania, Arizona and Florida.

“One option would be to call every single Rita Krill here but we may be able to actually narrow that down a bit,” said Silverman.

Visual and auditory clues in videos can help build a picture – from signs and license plates to clothing and accents – and in this case the swaying palm trees and swimming pool in meant “we could probably rule out New York and Pennsylvania”, he said.

“In order for this to be real there would have to be an actual thunderstorm in the place. So if there’s a Rita Krill in Naples, Florida, let’s see if there was a thunderstorm in Naples, Florida around the time the video was uploaded.”

Wolfram Alpha can help here, as a ‘computational knowledge engine’ which stores historic weather information, among huge amounts of other data. The original video was uploaded on October 5, and searching Wolfram Alpha for “weather in Naples Florida on October 5 2012” reveals that there was indeed a thunderstorm that day.

Wolfram Alpha can find weather data for locations around the world “going back decades” said Silverman

Storyful also check out any mentions of a storm in Florida on Twitter, and found a local weather account which corroborated the report.

“So now we’re feeling pretty good about Rita in Naples, Florida, there’s one other thing we can do thanks to Google Maps and Spokeo, we can get a look at the house where they say Rita Krill is.”

This may be “getting a bit creepy”, he said, but the position of the swimming pool relative to the house and the surrounding trees match with the video.

A screenshot from Google Maps of the video’s location, with the position of the tree highlighted, via Storyful

“So based on the name, the weather in the area, the location and what we can see of her house, this look like the right Rita Krill. At this point we need to get on the phone.”

She was “very happy to talk about” the video when Storyful called her and very excited about the event, “talking very emotionally, very personally about the experience” in a very believable manner, Silverman said, in comparison to the hesitant and unsure testimony of ‘Marie Port’ from the previous example.

She also sent a photo of the tree that was struck by lightning which can be checked with an Exif data viewer and corroborated further. Storyful verified the video and a number of news organisation picked it up to broadcast and publish, including interview’s with Rita herself.

Steps

Who shot the video and when?

What can the video tell us about date and location?

Tools

Spokeo

Wolfram Alpha

Twitter search

Google Maps

Telephone

Spotting hoaxes

The day before the Super Tuesday Presidential primaries in the US, an article appeared online looking exactly like a New York Times story, claiming senator Elizabeth Warren had endorsed Bernie Sanders for President.

The article was a fake, and the New York Times sent a cease and desist letter to the owner of the website which published the article, but it had already spread far and wide.

“In the 48 hours it took for that to happen, the video had been viewed 58,000 times and shared on Facebook more than 40,000 times,” said Stearns.

A fake story of this nature can sway votes and change the course of democracy, and this was not the first time such fake articles have had an affect in the real world.

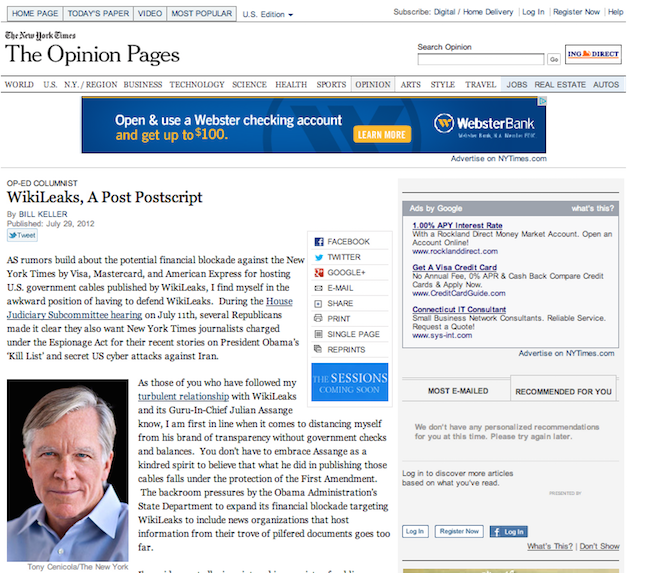

A fake Bloomberg article reporting Twitter had received a $30bn takeover offer last year caused shares in the network to spike, and Wikileaks published a fake New York Times article in 2012, in which then-editor Bill Keller falsely pledged his support to the organisation.

Checking the URL of any article is a quick and easy step to spot fakes as, in the case of the Bernie Sanders article made using CloneZone. The fake Bill Keller article had a slightly different URL to the real NYT opinion pages, and the Bloomberg article about Twitter appeared at ‘bloomberg.market’, another fake site.

The fake bill Keller article, created by Wikileaks

The style of an article can also provide clues, said Stearns. Spelling mistakes, an odd tone or writing style, a faked bylines or authors who seem out of place can all be the signs of a fake.

And just as with photos or videos, understanding the source of a story and who shared it first can give information about where it came from. The fake Bill Keller story was first shared by Wikileaks accounts and a fake @NYTKeller account with one letter ‘l’ replaced with a capital ‘I’.

WhoIs searches are another powerful technique to look at a website and find information about who registered it, “kind of like a deed for a website” said Stearns. The hoaxer behind the Bill Keller story was smart enough to give the same name to register their site as the real NYT website, but on a much later date.

“Finally, you can dig into the source code,” said Stearns, which “isn’t that easy and you have to know what you’re looking for”. Information in the headers and footers of a website’s source code can show up anomalies that wouldn’t fit with an original article

Steps and tools

Check the URL

Check the style

Find out who shared it by searching for the URL on social platforms

Do a WhoIs search

Check the source code (right-click to “view source” in a browser)