In the months before the Bundestag election, there was a lot of fear that disinformation might influence voters. It is clear that the worst-case scenario has not become reality: experts generally agree that such information did not largely affect the election outcome.

But misinformation still made headlines. Moreover, this content still contributes to our understanding of what kinds of false and misleading information emerges about elections. This is critical to understand if we want to be better prepared for the next election in which mis- or dis-information does play a significant role.

Now, with dust settled, and the verdict about misinformations’ influence on the German election rendered, it’s time to provide an overview of the broad spectrum of misleading posts that circulated. To do so, I use First Draft’s 7 types of mis- and disinformation typology.

1. Satire or Parody

Sometimes a conspiracy theory starts out as a joke. In April 2016, the satirical website Der Postillon posted an article that suggested the right-wing populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) was founded by Chancellor Angela Merkel herself, in order to have full control of the political debate in Germany. Many users laughed about this story, which generated nearly 39,000 shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook—strong engagement for Germany. Still, some were fooled and posted comments such as: “I really don’t want to know what we, being naive, manipulated and uneducated, don’t know. We would all be enemies of the state…” As often happens with satire, some readers did not understand the article was a joke and took it seriously. The website Mimikama.at debunked the story.

This conspiracy theory continued to be shared, because the joke was taken out of its original context. The original article by Der Postillon included a made-up document that included Merkel’s “signature”; on Facebook, people shared a screenshot of this document instead of the article.

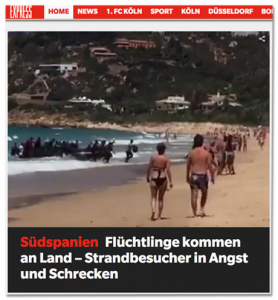

Falsely connected headline from Express

2. False connection

The refugee crisis remains polarizing, and exaggerated headlines fueled a heated debate. On August 10, the German tabloid Express published an article with the headline: “South of Spain: Refugees come ashore – beachgoers in fear and dread.” Yet, if you read the whole article, there is no mention of tourists in fear or panic on the beach. The story includes an eyewitness video of the scene, which is in stark contrast to the headline. The video shows tourists looking relaxed and walking on the beach as asylum seekers leave a boat and run ashore.

The German blog Bildblog.de, which monitors tabloid media, criticised the report: “For a few more clicks, express.de is making up a headline that has almost nothing to do with reality, and causes the spreading of a fear and dread of refugees.” Express later changed the title to “Beachgoers surprised: Boat reaches coast – refugees are storming ashore.”

3. Misleading content

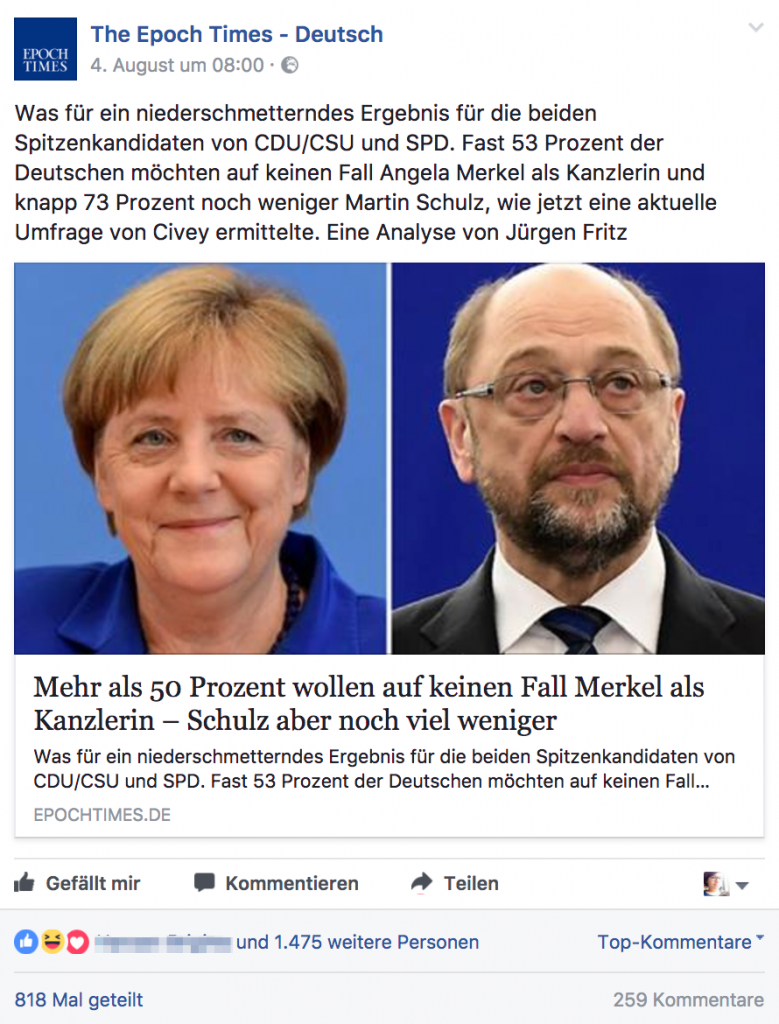

Misleading article from The Epoch Times

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her opponent Martin Schulz from the Social Democratic Party (SDP) were targets of many misleading stories. These articles were often based on factual information, but with the facts twisted.

On August 4, the website Epochtimes.de, which has a reputation for sensational news coverage, wrote: “More than 50 percent of Germans absolutely do not want Merkel as chancellor, but even fewer want Schulz.” This statement was based on an online survey by Market researcher Civey.

The poll asked who Germans would prefer as their next chancellor. 47.5% said that they would want Angela Merkel—healthy numbers in a multi-party system. If you read the article carefully, the Epoch Times mentions the correct number, but puts a spin on it, suggesting most Germans “absolutely do not want Merkel.” Yet the poll never asked this question. The article generated nearly 11,000 shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook, and some angry reactions from voters, calling Merkel and Schulz Volksverräter, which means “betrayers of the nation”.

Misleading content was one of the most common problems in the German digital debate: One of the most successful articles reported, headlined “Angela Merkel hopes for 12 million immigrants,” appeared in conservative Austrian newspaper Der Wochenblick. German news outlet Der Spiegel reported on the story and judged it to have “no factual basis”. Even so, the Wochenblick story generated 40,000 likes, shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook, making it one of the most engaged articles about Merkel on the social media platform this year.

Falsely contextualized CDU image

4. False context

An easy way to engage conservative or right-wing readers is to criticize the Antifa, the anti-fascist network in Germany. After the protests in Hamburg during the G20 summit in July, posts critical of Antifa were popular. One example is a photo on Twitter that showed a young woman with a stone in her hand. The image also included the logo of the Antifa and a slogan suggesting that “Flora” wanted to defend squat houses.

The photo is not fake, but was taken out of context. The young woman in the photo is a representative of the conservative Christian Democratic Union’s (CDU) youth organization. In a video from 2016, she posed with a stone in her hand saying: “All extremists are trash.” Her name is Antonia Niecke, as fact-checkers from ARD Faktenfinder reported. This photo started out with left-wing activists, who used the screenshot of the video to mock the young conservative politician. Right-wing activists later copied it in an attack on Antifa, and even AfD retweeted it.

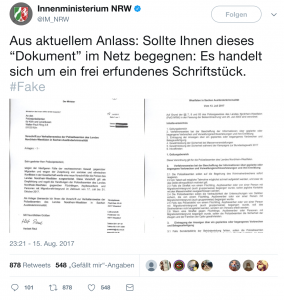

Tweet about fabricated Reul letter

5. Imposter content

During the US elections, several imposter news websites tried to look like well-known media brands. In German-speaking countries, imposters use a different strategy: impersonating public authorities. During the refugee crisis in 2015, there were fake letters from municipalities claiming every citizen would have to accommodate asylum seekers in their home.

Imposter content made headlines again with a fake letter claimed to be by the State Minister for Internal Affairs in North Rhine-Westphalia, Herbert Reul. The letter included new regulations for the police, directing them to ignore and conceal crimes committed by refugees.

The forgery looked like an official document and spread quickly on Facebook. Even well-known journalist Matthias Matussek and a former politician from Merkel’s conservative party, Erika Steinbach, shared the letter. Reul called the document an “audacious forgery.” Even though the State Ministry for Internal Affairs reacted quickly, the document continued to circulate on social media for several days.

6. Manipulated content

CDU, Merkel’s party, used the slogan “For a Germany in which we live well and gladly.” A picture was circulated, giving the impression that the governing party of East Germany, the Socialist Unity Party (SED), had used the same slogan on a poster publicising the party conference. Association with communist leaders strikes a chord with angry voters who call Angela Merkel a dictator and an enemy of the German people. Fact-checkers at Mimikama.at quickly found the original source of the image, and debunked the fake photo.

7. Fabricated content

Facebook post with fabricated Merkel quote

Completely made-up news stories mimicking traditional journalism had little to no impact on the election. Far more common were the hyper-partisan Facebook groups using fabricated documents and quotes by politicians.

Such quotes often do not reach a broad audience, but German users who are part of anti-Muslim and anti-refugee Facebook groups see this kind of content very often. These groups posted a succession of photos of candidates with outrageous and untrue quotes next to their face. One old but widespread quote shows Angela Merkel saying: “We should not use attacks like in Paris to incite islamophobia, but accept them as a part of our lives to not risk the integration of our Muslim fellow citizens.” However, there is no record of her ever making the statement.

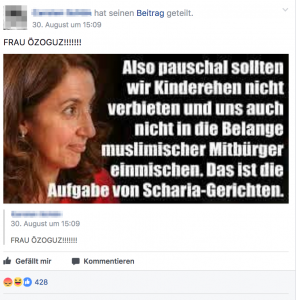

Another fake quote targeted integration commissioner Aydan Özoğuz, deputy chairperson from the centre-left SPD and daughter of Turkish immigrants. Next to a photo of her, the quote read: “In general, we should not forbid child marriage and also not interfere in the concerns of our Muslim citizens. This is the responsibility of Sharia courts.” This fabricated quote was circulated on Facebook shortly after a member of the AfD suggested Özoğuz should be “disposed of in Anatolia.”

Facebook post with fabricated Özoğuz quote

Right-wing populists were also targeted with fabricated quotes. For example, there is no proof that Frauke Petry (newly elected member of the Bundestag) said “the earth is flat”. Mimikama.at revealed this hoax was published on a website that allows users to write their own articles. Below these articles is a disclaimer that the content is made up. However, readers do not always read the whole piece, and are often fooled. Fact-checkers at Correctiv.org, which worked with First Draft to report daily to newsrooms on mis- and dis-information in the lead-up to the election, debunked a number of articles from this hoax site.

Conclusion

The volume and maliciousness of disinformation never reached the level that it did in the lead-up to the elections in France. But some trends did emerge. Still, many pieces of disinformation focus on the topic of refugees and Muslim immigrants, and individual politicians were often subjects and victims of false information. Mis- and dis-information circulated within narrow target groups, such as anti-Muslim Facebook groups, and regionally based communities.

Ingrid Brodnig is an Austrian journalist and author. Her new book, Lügen im Netz (English translation: Lies on the Internet), was published. Her book explains the role of misinformation in the digital debate and the influence of populists on social media. brodnig.org