Social unrest is always hard to cover. These protests have been particularly difficult for Black journalists whose personal experiences with systemic racism are colliding with the degradation of the profession. First Draft strongly believes that Black lives matter, and that journalism is not a crime.

Social media has leveled the playing field of mass communication and, in some ways, helps make the protests sparked by the death of George Floyd possible. Mobile technology has shone a light on the treatment of Black people by police, allowed crimes to be documented, helped protesters to organize and shown the violent response from law enforcement to the world. Continued coverage of the protests is public-interest journalism at its most raw and many of those directly affected are broadcasting events in real time.

Finding newsworthy material online is relatively straightforward. Verifying it and then using it ethically is more difficult. This article will address all three elements, as well as tips for supporting yourself and your colleagues when covering a story.

Online newsgathering

Before we discuss the details of how to find newsworthy material online, it is important to recognize the impact and responsibilities of journalists and news organizations in using it.

Using eyewitness media from protests can identify both the individuals in the footage and specific social media accounts, potentially putting both in harm’s way. Embedding posts in a news article online is essentially opening a window for readers onto that person’s life. News organizations should apply the same guidelines around consent and protection of sources in the online world as they do offline, or risk endangering sources, damaging their own reputation, or attracting legal action.

Twitter is still the social network most people think of when it comes to news, and Tweetdeck is still the best tool for finding information on Twitter quickly.

The free-to-use dashboard lets users set up columns of searches, like lots of individual newsfeeds, then filter the results by things such as the level of engagement or media type.

To get the best results, we will need to fine-tune our search using a Boolean search string to look for specific keywords. Brainstorm some keywords witnesses or sources might use when tweeting about the event and combine them with the location. Add “me OR my OR I” if you are looking for people talking about their personal experience. Remember to use quote marks for phrases.

Then use AND and OR to separate out the different sections of the search. Use brackets to more clearly mark the different sections if necessary.

Here is an example you can copy and paste, filling in the relevant location keywords:

[location] AND (protest OR protesters OR protestors OR #blacklivesmatter OR police OR officer OR arrest* OR attack* OR charge OR shoot OR “pepper spray” OR mace OR curfew OR riot OR loot OR “rubber bullet*” OR “pepper ball” OR “tear gas” OR “far right” OR “far left” OR supremacist OR boogaloo OR antifa) AND (me OR my OR I OR we OR us OR our)

Read more: First Draft’s Essential Guide to Newsgathering and Monitoring on the Social Web

If the search doesn’t return results, it could be because there is a missing part of the search string, such as a solitary quote mark, or because it is too long. Tweak it until you get results and use filters to cut down on noise and irrelevant posts.

Twitter may be the easiest social media platform to search, but that doesn’t mean it has all the relevant material. The vast majority of social media users are not on Twitter, so searches here will only be a small window into the true level of online activity about a particular issue.

Facebook and Instagram

In July 2019, Facebook effectively took a hammer to many of the newsgathering tools and techniques journalists and researchers had built up around the network. Almost a year later, the search options are limited.

People looking for information on the world’s biggest social network can use its standard search functions, on the website or in the app, then filter the results. Open-source intelligence (Osint) communities discuss editing the URLs of Facebook searches for more refined searches but the social network is constantly changing, making it difficult to keep up.

Instagram is a bit more versatile. Searches on the app or website on specific hashtags will return results sorted algorithmically, but the online tool Wopita, formerly Picbabun, will show most recent results first. It will also show users associated with certain keywords or phrases, and any related hashtags.

Alternatively, there’s CrowdTangle, a social media analytics tool owned by Facebook, which is free for journalists and researchers. Users can set up lists of public groups and pages to monitor and save searches of relevant keywords across Facebook, Instagram, and Reddit.

TikTok

TikTok now has more than 800 million users worldwide, was the second-most downloaded app in 2019 and has been used widely by people involved in the protests.

You can search for hashtags, keywords, or accounts on the mobile app, and it will show you the results and other relevant hashtags, which can help in the search.

On desktop there is no such search function, so tools like OsintCombine’s TikTok search can help for users and hashtags. Remember that TikTok hashtags can have emojis.

Also remember that with all kinds of online newsgathering, verifying newsworthy information is a crucial next step, and always treat contacts and sources with respect.

Verification

Whether it’s coronavirus or protests, when covering emotionally charged stories we need to be emotional skeptics. Disinformation spreads rapidly, particularly when it appeals to our emotions, and those same emotions can make us subconsciously more likely to believe certain claims or footage.

Whether you’re looking at a video, a tweet, or an image from a protest, First Draft recommends thinking in terms of the five basic checks anyone can perform. For more details, see First Draft’s “Essential Guide to Verifying Online Information“.

Is it the original?

The first step in verification is finding where the video originated. A reverse image search is often the fastest way to ascertain whether an image or video has been used before in a different context.

The RevEye browser extension allows users to search multiple image databases for a match. InVid is an invaluable tool for analyzing and verifying videos.

Been seeing some fake photos circulating that appear to show US protesters asking China for help. Not sure who photoshopped them or why, but be careful and reverse image search on TinEye or Google before sharing protest photos. pic.twitter.com/GqYSWf4JlE

— Shelley Zhang (@shelzhang) June 1, 2020

If no other versions appear, see if the user will send you the original image or video through other means than social media. Exif data in the image file can corroborate what the source says about the circumstances in which it was taken — but that information is wiped when posted on the platforms.

Who is the source?

Look at the social media profile of the source for examples that would support the person’s claims. Are there other pictures from the scene on the person’s account? Does it make sense that the person would post the type of content you wish to verify? Contact the person directly before making any claims about their identity. In the case of protests, someone may wish to remain anonymous for safety reasons. (See the section below on ethical reporting.)

When was the picture or video captured?

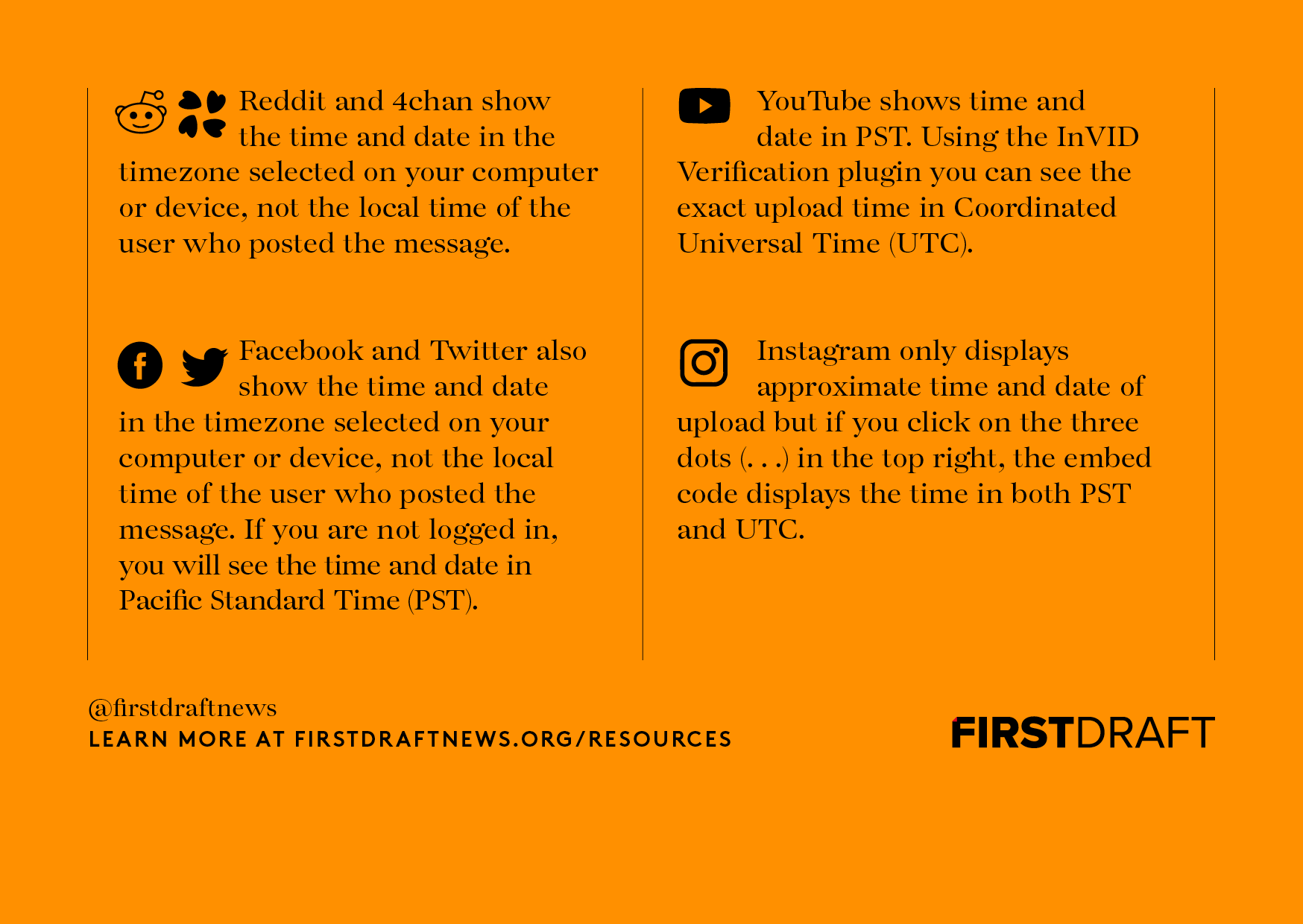

Even before speaking to the source, look to the weather and time of day to establish whether the content passes basic common-sense checks. Remember that the main social media platforms have different ways of determining timestamps. Read more about this in First Draft’s Essential Guide.

Where was it captured?

Now is the time to flex your observation skills. Look for recognizable landmarks, street names, or shop names to cross-reference the location with a mapping tool.

If details are difficult to make out, and with the knowledge that geotags can easily be manipulated, digging into the account that posted the content for clues can be the way forward. Did the person make note of their location in other posts? Does it make sense that the poster would have been present, or is there anything unusual about the account?

36. An anonymous account created today is sharing a fake photo claiming it’s of the protests. It’s hiding the replies that correctly say the image is from Designated Survivor.

Be careful folks, lots of this going around. pic.twitter.com/SXJivY2WG1

— Jane Lytvynenko ??♀️??♀️??♀️ (@JaneLytv) June 1, 2020

Why was it taken?

This can be the hardest question to answer, but it should still be top of mind throughout your verification. A reliable way to get a sense of why the content was captured is to speak directly with the source, but trying to glean more about their motivations from their account is possible. Perhaps they were simply a bystander, but you can still look at their account and other posts for potential motivations or affiliations that might influence their perspective on the scene.

Verification goes beyond just pictures and videos. Avoid amplifying claims that protests are subject to “outside agitators” — such as antifa, George Soros, white supremacists or Russian trolls — without hard evidence. Verify claims by law enforcement as you would any other statements.

For more on online verification, the recently published “Verification Handbook For Disinformation And Media Manipulation,” edited by BuzzFeed News’ Craig Silverman with contributions from experts, is filled with techniques for investigating social media accounts, platforms and content.

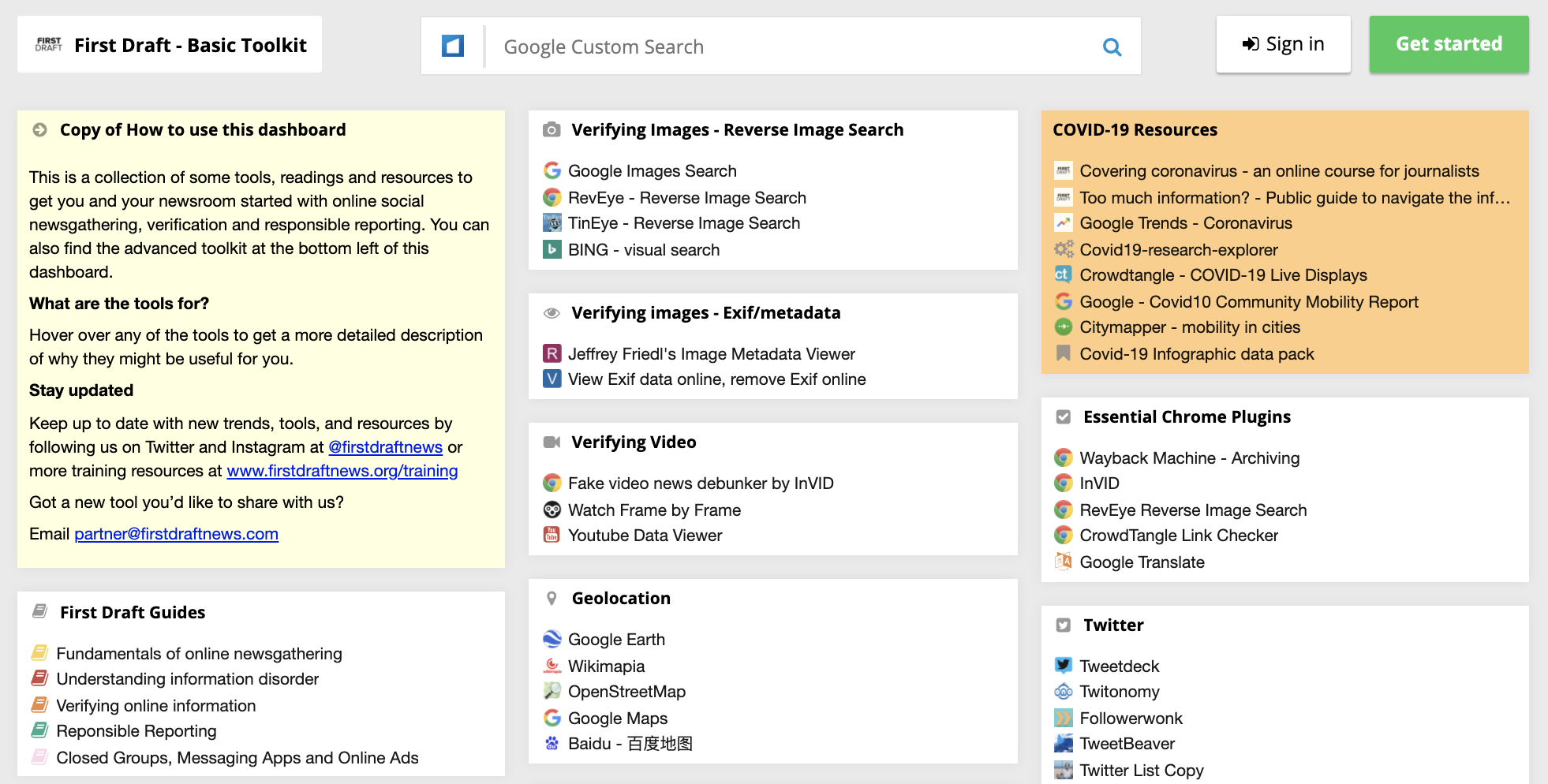

First Draft has collected a number of newsgathering and verification tools together in a dashboard for easy access. Screenshot by author.

Use it ethically

Gathering and distributing eyewitness media raises a range of ethical concerns.

For example, amplifying accounts or individuals in reporting can raise that person’s profile and draw unwanted attention to them.

Before quoting from, linking to or embedding a post about the protests, consider the impact on the user and the people in a picture or video. Seek informed consent for the use of their content, directly from the person who posted it. Always ask whether and how a source would like to be credited, make sure they know the possible repercussions, and give the source the option not to be credited at all.

Being transparent about how you will use any material is also vital in building trust.

We need deep, meaningful coverage of the impact of racism on our communities and our nation. How newsrooms tell these stories matters profoundly, and doing it right means pushing back on some old journalism practices, norms and culture. Here are three resources to help. /1

— Josh Stearns (@jcstearns) June 1, 2020

Protests and surrounding events can be particularly volatile, so consider the emotional state and physical safety of contributors who are live streaming or posting. When communicating with members of the public in dangerous situations, journalists should urge them to stay safe, reads the Online News Association (ONA) Build Your Own Ethics Code project. “Sometimes it’s best to wait until after the danger has passed.” If they are potentially in immediate danger, consider waiting to contact them.

Particular sensitivity is required when the source or subjects featured in footage are from vulnerable communities. WITNESS Media Lab asks journalists to protect the anonymity of sources at risk for exposing abuse. This goes beyond not publishing the source’s name — according to WITNESS, the journalist should also consider whether the footage contains metadata that pinpoints the source or their location, and whether the platform hosting the footage could reveal identifying details.

Finally, as with all reporting, providing context behind the events is crucial. Look beyond “riot porn”: social movements and unrest build over time and manifest themselves in waves of visibility created by political opportunity.Marches don’t get automatically organized, protests don’t appear out of nowhere. The networks of support underlying mass mobilization are communities we need to report on and engage with before and after they take to the streets.

While covering a George Floyd-related story in Emeryville last weekend, some cops in riot gear thought I was a looter.

Law enforcement doesn’t see enough black reporters on a daily basis. This is indicative of a much larger problem in the news business https://t.co/ogQsoDZ4RV— Justin Phillips (@JustMrPhillips) June 4, 2020

Look after yourself and your colleagues

Monitoring around-the-clock events that involve scenes of violence and suffering can take a mental toll. Advice from First Draft’s 2017 guide to journalism and vicarious trauma is still relevant today: Pace yourself so that distressing work is alternated with more positive experiences and take regular breaks when you are required to work with distressing material.

To reduce your exposure to the material to the strictly necessary, consider watching and listening to only what you need to complete the task at hand. Muting violent videos or adjusting your monitor to grayscale instead of color are a few ways of limiting the possibility of vicarious trauma from reporting.

Hey journalists! #CPJEmergencies‘ safety advisory on covering the U.S. protests over police violence outlines the risks journalists need to consider when covering the protests.

Please read, bookmark, and share.https://t.co/ngQVWvdAJt

— Committee to Protect Journalists (@pressfreedom) June 1, 2020

Checking in with colleagues regularly and exchanging updates about how your work is affecting you is one way of maintaining a sense of togetherness during stressful times, especially when many people are working from home.

“Social isolation is one of the risk factors for physiological distress, and social connection and collegial support is one of the most important resilience factors,” Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, previously told First Draft, citing research into journalists covering traumatic events.

For managers and newsroom leaders, actively looking after your employees’ mental well-being during this time is essential. Have regular check-ins with staff and stay alert for signs of vicarious trauma. Consider the volume and content of protest-related materials to which your team is exposed and ensure there is variety in their working week, with time periods where their duties do not involve interacting with distressing content.

Crucially, this also means letting go of “hyperproductivity” and encouraging switching off outside work. Be realistic about what output you expect your reports to produce, and focus their efforts on what is most achievable and valuable, Amnesty International’s Crisis Evidence Lab head Sam Dubberley says. Let your employees know they don’t need to be online around the clock and don’t undermine that with your own working practices and habits. In fact, being a role model and sharing your own self-care tactics can help staff look after their own mental well-being.

Social unrest is always hard to cover. These protests have been particularly difficult for Black journalists whose personal experiences with systemic racism are colliding with the degradation of the profession. We recognize and empathize as a newsroom that Black lives matter, and that journalism is not a crime.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

The headline, sub-head and first paragraph of this article have been updated to clarify the immediate and long-standing reasons behind the protests.