Facebook has been rolling out the ability for users to livestream directly from the network’s app for a few months now, and this week the biggest social network in the world unveiled an interactive map for users to find and view live broadcasts.

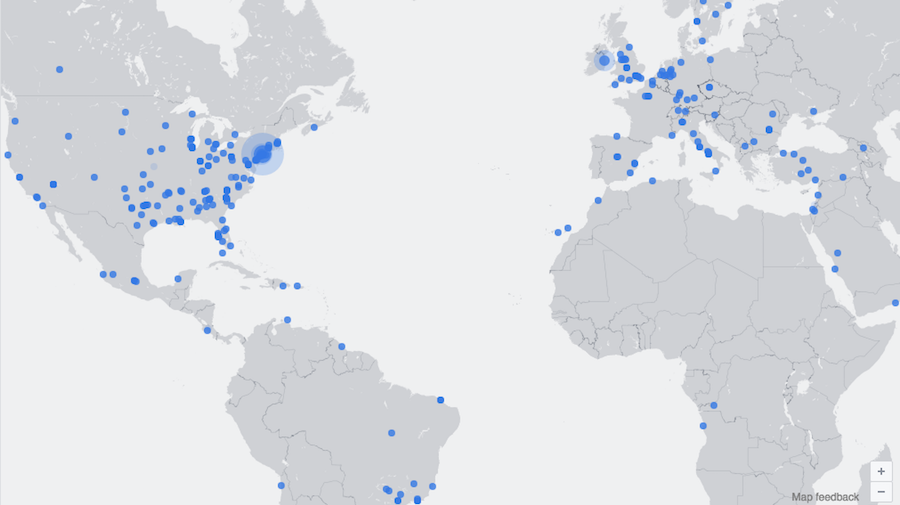

Active livestreams are displayed as blue dots which users can zoom in on to get a closer look. Hovering over a dot will bring up the livestream, and a sidebar of the most popular streams is ever-present on the left. So what use could this new function be for journalists and breaking news?

Facebook Live appears to be very popular in South East Asia in late afternoon, compared to mid-morning in Western Europe

With Facebook Live active in more than 60 countries, potentially being available to all 1.6bn monthly active users in the future, the possibilities are certainly present for news organisations to find streams from breaking news events.

The map is not without its limitations, however. On its most powerful ‘zoom’ setting the map displays an area of around 160,000 kmsq – slightly smaller than Kansas, slightly bigger than Bulgaria – making zeroing in on a specific location almost impossible. This presents a problem when looking for livestreams from urban centres, where the greater population density suggests a higher probability of livestreams around breaking news.

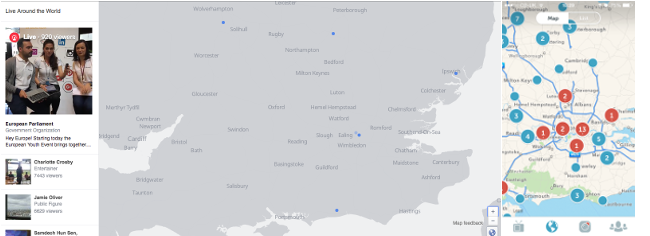

In contrast, the map for Periscope, Twitter’s livestreaming service, lets users zoom in on areas down to street level, which has allowed journalists to find livestreams from the scene of the Paris attacks, the attacks in Brussels, the San Bernardino shooting, refugee camps in Europe and last year’s bombing in Bangkok, to name a few.

While Periscope has had almost a year’s headstart on Facebook Live to establish a userbase and develop its functionality, the number of livestreams displayed on the map is surprisingly low for some areas.

Livestreams on Periscope appear as red dots (right) and saved broadcasts in blue. Periscope significantly outnumbers Facebook Live (left, at full zoom) in terms of live broadcasts. At mid-morning in the UK there were 20 users livestreaming in around the London area on Periscope, compared to one on Facebook live.

In keeping with the veil of secrecy which surrounds much of Facebook’s operation, there is no clue as to whether the available livestreams are filtered. First Draft is in contact with Facebook for clarification on these issues but has yet to receive a reply at the time of writing.

Check out: How can newsrooms verify live video from eyewitnesses?

The increase in livestreaming capabilities provided by social networks also raises its own ethical issues.

While embedding content from social media skirts any potential copyright issues, news organisations have no control over what may be broadcast. This was brought into stark relief last August when Derek van Pelt, an eyewitness to the Erawan shrine bombing in Bangkok, began livestreaming the resulting carnage on Periscope minutes after the explosion.

Viewers’ reactions moved from praise to horror as Van Pelt unwittingly broadcast the gruesome aftermath.

“Sorry, that was disturbing,” he said in the footage, “I didn’t actually know what it was because everyone just gathered around.”

Periscope is also at the centre of a number of criminal investigations involving an alleged rape and apparent suicide, both of which were livestreamed to the world.

There are also serious questions about the intended audience and consent, after a Californian man livestreamed the birth of his son on Facebook Live earlier this week. He told People magazine he thought he was only broadcasting to his friends and family but many news organisations embedded the footage regardless, without asking his permission or that of his partner. He shrugged off the publicity as “a positive”.

The ability for viewers to offer feedback or encouragement raises still more areas for concern by the new technology, particularly in breaking news. While Van Pelt filmed the aftermath of an explosion, there will be other cases of amateur livestreamers documenting an ongoing situation which could place them in danger. Syrian activists who used Bambuser to livestream the shelling of cities in the early days of the country’s civil war quickly became military targets themselves.

There is no doubt that Facebook Live and other livestreaming services have the potential to be powerful tools for journalism and democracy, and the ability to both broadcast and access such streams will only improve. Issues of ethics and verification in livestreams have previously been covered here at First Draft and elsewhere, but serious questions still remain.