The coronavirus outbreak has brought with it a number of new ethical challenges for newsrooms and reporters.

Social media users are sharing their experiences with the virus which can have real and damaging impact on their lives. There has been an uptick in conspiracy theories and misinformation as the world attempts to follow the ever-evolving science around the virus. And much of the misleading information is flourishing in private spaces that are difficult for researchers and reporters to monitor and even harder to trace.

First Draft’s co-founder and US director Claire Wardle and ethics and standards editor Victoria Kwan discussed the tricky ethical terrain that is covering coronavirus in a recent webinar session on May 14. Read on for key takeaways from the session, watch the full webinar below or on our YouTube channel.

Traditional journalistic ethics still apply online

Facebook’s pivot to privacy last year saw the platform recognise a growing preference from users to communicate one-to-one or with limited groups of friends online.

“We’ve seen people move into smaller spaces with people that they trust, people that they know, people that believe similar things to them,” said Claire Wardle.

But this has had important implications for those covering and researching misinformation during the coronavirus outbreak. While it’s crucial to be aware of and publicly counter rumours and hoaxes shared in private spaces, there are a number of ethical questions reporters and newsrooms should set out to answer before entering them.

In many ways, these considerations aren’t so different to those commonly found in traditional journalism: balancing privacy versus public interest, as well as security versus transparency.

“If we’re thinking about reporting from these spaces, what does it mean if ultimately these people believe that they are in a space that is private?” asked Dr Wardle.

“If you can join that group, you can get access to that information and as ever with journalism, it’s that tension with privacy versus public interest.”

Sometimes the public interest case is clear: gaining knowledge from a group discussing future anti-lockdown demonstrations could be of vital importance to the health and safety of the public. In contrast, a closed community where individuals are sharing their experiences of being affected by Covid-19 may not pass the same public interest test.

This also brings up questions of security versus transparency. “For certain types of journalistic investigations, you have to consider this as if you were going undercover,” said Wardle.

“Of course, wherever possible, be transparent but also think about your own security.”

And the burden of considering these questions should not rest solely on the individual reporter — it necessitates a top-down approach from newsrooms, according to Dr Wardle:

“The things we’re talking about today really need to be enshrined as part of a newsroom’s editorial guidelines.”

Adopt a people-first approach

The coronavirus outbreak is a news story with a profound impact on people’s lives. For this reason it is crucial that journalists covering aspects of the crisis adopt a people-first approach, even when venturing online in their reporting.

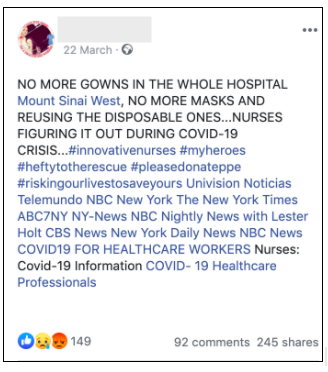

When seeking to use online testimony from users in reporting, First Draft’s ethics and standards editor Victoria Kwan highlighted the importance of considering the intent of the person posting — especially when they’re not a public figure.

“Sometimes people don’t realise that their posts are public, and sometimes they do but they haven’t thought through the potential consequences,” she said.

Giving the example of a nurse who published a Facebook post about lack of PPE and tagged a number of media outlets in the caption, Kwan illustrated that there are instances where the poster clearly wishes to get publicity. But, she added, even in these examples it’s vital to talk through the potential impacts of your coverage with the individual, outlining the benefits and drawbacks of receiving media attention.

The theme of adopting a people-first approach is also an important aspect of covering conspiracy theories, which have experienced a considerable boost since the beginning of the crisis according to researchers.

For this, Dr Wardle pointed to the human psychology behind such theories.

“When people feel powerless and vulnerable, it makes them much more susceptible to conspiracy theories,” she said.

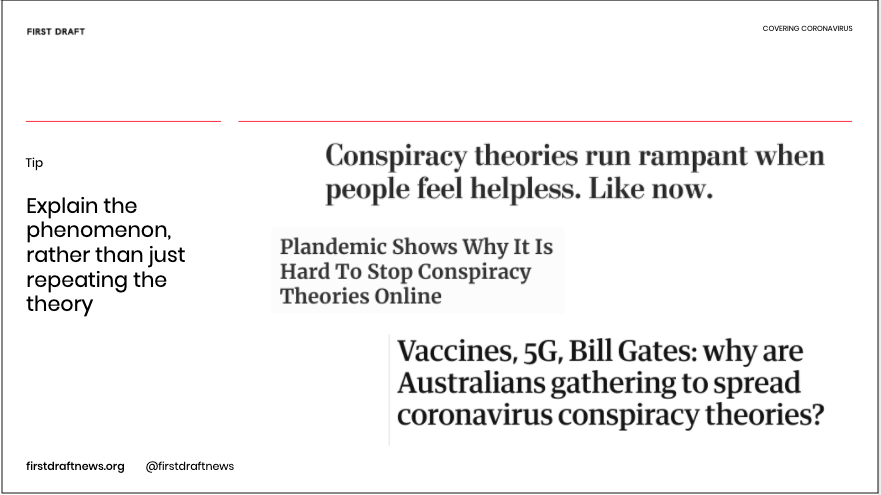

Newsrooms and journalists should avoid using derogatory language when referring to conspiracy theories and the people who share them online. Prioritising empathetic reporting is key, she said. Reporters should seek to explain why certain theories take root, rather than simply debunking them.

“As societies, we need to have more conversations around why conspiracies are taking off, what is it in society that makes them so appealing, and to talk about the psychological mechanics of conspiracies rather than: ‘these people are crazy, that’s stupid, let’s debunk the stupidity,’” said Dr Wardle.

Screenshot from webinar slide — examples of explainers rather than debunks

Be aware of the ‘tipping point’

From false links between 5G and the coronavirus to conspiracy theories around a potential vaccine, a huge ethical consideration for journalists is to avoid amplifying dangerous or misleading information.

Wardle cited the recent case of the viral “Plandemic” video which contained a number of falsehoods. While initially some newsrooms avoided reporting on it for fears of “giving it oxygen”, the video eventually gained so much traction that reporters realised it needed mainstream coverage.

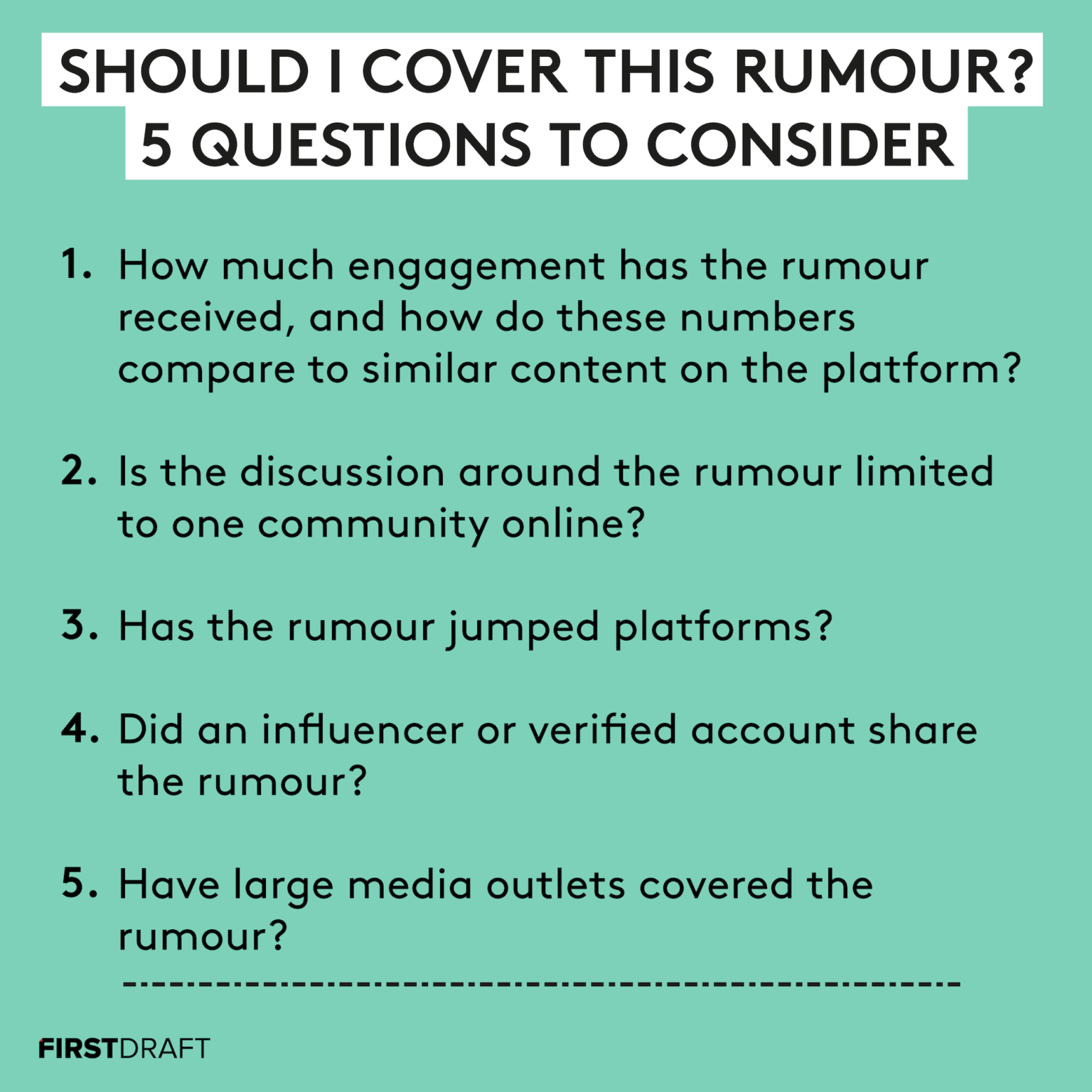

It’s not always straightforward to decide when to cover mis- or disinformation. For this, Dr Wardle has coined the idea of the “tipping point”. On a case-by-case basis, there are a number of questions to ask before covering misleading content:

The idea of the tipping point is also key when investigating closed groups or messaging apps, where it may be difficult — sometimes impossible — to retrieve data about the spread of a piece of misinformation. How can you quantify the spread of a rumour when it leaves no trace?

Dr Wardle advised looking for examples of whether the content is being shared to other platforms as a way of determining whether or not it is being circulated widely.

Finally, she warned that sometimes mis- and disinformation is deliberately created by certain actors with the aim of reaching coverage from mainstream news outlets.

“Often things are seeded within closed messaging apps with the hope that it will then grow, move into social media and then be picked up,” said Dr Wardle.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.