Time and time again, the first reports from the scene of breaking news are shared by eyewitnesses with smartphones and social media accounts. Whether a photo, a video or a panicked string of text, people can share what they are seeing with the world in real time, making the phenomenon central in how news organisations report an event.

With a slogan like ‘First for breaking news’ the pressure is on at Sky to find, verify and publish the right information around any developing story, and often that responsibility falls to Hazel Baker, digital editor for newsgathering at Sky News’s UK offices.

“Sky is clearly divided into newsgathering and production,” she told First Draft. “There is a digital editor in output but I’m the digital editor in newsgathering… We’ve got the home news desk and foreign desk and my sphere is working across them, aiding both of them in finding breaking news stories and furthering our search with non-breaking news stories.”

The Charlie Hebdo attacks in January were a turning point for Sky, Baker said, in understanding how important a role eyewitness media plays in a breaking story and how it should be dealt with in the newsroom. The ferocity of and interest in the shootings, which began with the murder of 11 journalists and a policeman at the Paris offices of the satirical magazine and ended with two hostage situations and a siege more than 30 hours later, made it unique in modern Europe and social networks were full of footage and speculation as to the course of events.

The first Baker heard of the attacks was a tweet from a French journalist, and by the time the Reuters news wires lit up and the news desk had become “a flurry of activity” she was already at work.

“At that point of my own accord I started the search process and ran a series of search columns on Tweetdeck, started looking on Instagram and any chatter on Facebook I could find. Within minutes all my colleagues were bombarding me and it became hectic really quickly.

“For me this is why it became such a watershed moment, because it really highlighted that you have to have a process, some collaborative working system where others in the newsroom can aid you on stories like this.”

Piecing together the implications in the days after the attacks, an important consideration for Sky – no doubt, for many UK newsrooms – was how the team would react if a similar attack were to take place in London. Baker took the lead in laying down that strategy and detailing how digital desks can better serve the newsroom as a whole during breaking stories.

“You need to think about delegating the tasks effectively and I suggest someone runs a geosearch while someone else runs a keyword search. Then once someone has exhausted any geosearch possibilities they speak to the person on keyword search and divide the keywords into the language used by eyewitnesses – so ‘me’, ‘my’, referring to themselves and swearing, quite visceral stuff – and exact locations.”

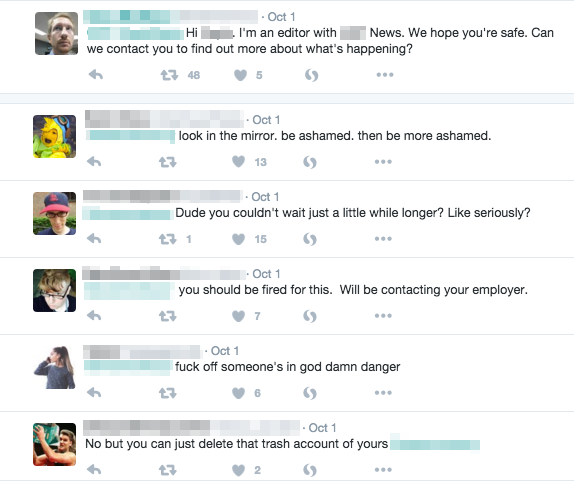

As sources are found and contacted the team add usernames and any other identifying information to a page in iNews, Sky’s newsroom management system of choice, to make it clear who has been approached and who has not. Multiple reporters from the same outlet contacting one source on social media became a particular problem during the recent UCC shooting in Oregon, when an eyewitness tweeted reports of a shooter on campus. The public’s response was venomous.

When an eyewitness to the UCC Shotting tweeted “OMG someone’s shooting on campus”, this was the first response. Many members of the public were not happy.

Public responses became more angry as more journalists got in touch

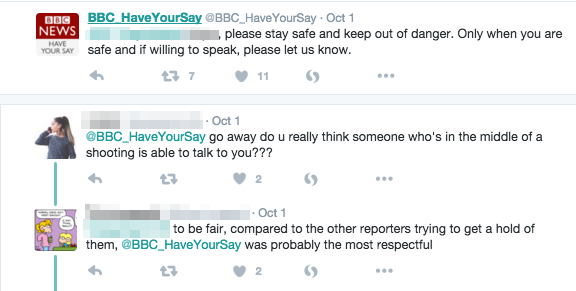

A BBC account received a better response for a more respectful approach. The source did not speak to any journalists about her experience.

Publicly contacting sources on social networks is a necessary evil of modern newsgathering – Baker has “cringed and typed tweets before” – but, at present there is no better way. It is important to consider whether getting in touch will only lead down a blind alley of public acrimony, however.

“I’d have to think there’s a really good chance of them replying,” she said, by either being one of the first to reply or banking on the Sky News brand to get a response from UK sources.

“I always look at not only their tweets but their @-replies [on Tweetdeck] as well, to see if they have started giving replies, and trying to gauge from that whether they’re likely to say yes or not. If it’s clear that they don’t I’m certainly not going to pitch in there. I think that should be a matter of protocol, having a look if they’re replying.”

She is currently working on a code of practice for Sky News journalists to turn to in the future, but the safety of eyewitnesses is also a vital concern for Baker and the industry more widely, not least because of the ability to speak to sources at the scene of a developing story much more readily than ever before.

In this case, public conversation “is definitely bad practice”, she said, and even when on the phone or in direct message conversations she said it is important to keep questions and conversations clear, direct and to a minimum, especially if the situation is still ongoing.

‘All of a sudden he said ‘I think I’m going to die’. I had no answer to that at all’ – Hazel Baker, Sky News

“Particularly if you have someone co-operative who wants to help, try to target the questions and not take up too much of the time, and certainly not distract them. Making it clear that if you need to move or stop talking at any time, stop talking and make sure you’re safe. And reminding people not to take risks.”

When covering the Peshawar school massacre in 2014, Baker was in contact with a man in one of the nearby buildings via direct message on Twitter.

“He was telling me what he could hear and all of a sudden he said ‘I think I’m going to die’. I had no answer to that at all. The only thing I tried to do was say ‘please stop talking to me now and put yourself somewhere as safe as you can. When this is all over get in touch’. And he did get in touch, he was fine.

“But I wonder if I did the right thing and what I would do if that happened again. That’s a personal thing I’m trying to grapple with at the moment, how we look after people in those situations. I think some of it is just to say ‘stop talking to me’.”

Email can be just as an important source of eyewitness footage and testimony as social media for established newsbrands and during June’s attack by jihadists on a Tunisian beach resort the Sky inbox was overflowing with reports from the scene.

Some had footage – quickly verified using satellite imagery and corroborating reports – some were offering to speak on air but others were locked in their hotel rooms watching the story unfold on Sky and asking for information.

“I was quick to stress that we don’t name anyone unless we know for sure they’re not in danger as we don’t know for sure this attack is not more than one person. We definitely don’t say where they are and we don’t show any video that is showing where they are. We have to understand that many are quite traumatised so eyewitness safety was a big part of that.”

And August’s Shoreham air disaster in the UK offered another important example of journalists’ responsibility to their sources from social media. The annual air show is billed as a day out for the family but this year was brought to an abrupt and tragic end when an RAF Hawk Hunter jet failed to complete a loop manoeuvre. It crashed into a busy road at 13:30 on a Saturday, destroying eight vehicles, killing 11 people and injuring 16 more.

‘You’ve got to work on the basis that you might meet these people again. Hopefully this will be the only news event they see and I wish them a peaceful life after that, but you never know.’ – Hazel Baker, Sky News

A video from the scene of the crash was found and licensed by a viral video agency, rather than a news outlet, and the two-minute footage showed the idyllic English countryside as a warzone of burning cars with bodies still inside, of debris and flattened street lights.

“In the video, the cameraman is laughing,” Baker said. “And it’s immediately obvious in hindsight that he’s in shock. I can’t imagine how you wouldn’t be in shock, witnessing that. But not everybody understands shock and what it can do to people.

“People watched that video – which was spread everywhere, in full – and that man got serious abuse on Twitter. ‘I can’t believe you’re laughing at that you worthless piece of crap’ and worse.”

Some news outlets ran the video with muted audio in parts, but the viral video agency “put his name out in full,” said Baker, “which I think was an error. I think they should have advised him. They should know better.”

The case of Jordi Mir, who filmed the execution of police officer Ahmed Merabet by the Charlie Hebdo attackers, is another well-documented example of an eyewitness chewed up and spat out by a media machine only interested in footage, and not the person behind it.

When handled responsibly, dealing with sources and eyewitnesses first contacted on social media is as much about building trust and relationships as it is with sources offline. When proper crediting is appropriate it can be a source of pride for an eyewitness and following up to provide links or screenshots, as Baker occasionally does, can reinforce the community engagement efforts of social media editors and producers on the output side.

“You’ve got to work on the basis that you might meet these people again,” Baker said. “Hopefully this will be the only news event they see and I wish them a peaceful life after that, but you never know. And if they’ve been treated well they’ll tell a certain number of people about their experience with Sky News. And also, now on social media, they can complain. ‘Sky did this’ and ‘Sky did that’… ‘I didn’t even get a credit for my pictures’.”

Every big, new story raises new questions and considerations for journalists working with eyewitness media and social sources, as the platforms and people’s relationship with them evolve. The horror of the attacks in Paris in mid-November, with 130 people killed across six sites in northern France, was an intensely complex situation to manage from a social newsgathering perspective, said Baker.

But in the end it yielded very few sources compared to January’s shootings at the Charlie Hebdo offices. Any filming or photography became less useful in understanding or retelling the facts because the attacks happened at night, but largely people were more concerned for their lives than documenting events. The instantaneous nature of many news stories means newsrooms need to react quickly though, and Baker plans to train a number of people in the newsroom with all the necessary skills and have an action plan for future events.

“The need for people hunting out UGC is quite fluid, it varies from day to day,” she said. “If it’s a quiet day on the news front they would be utilised doing other things but if it’s busy then we have to prioritise in the first few minutes. So it’s about identifying who in the newsroom can be multi-skilled to do that.”

This largely boils down to communication and preparation. When a big story breaks, everyone needs to know who is working on what and what stage different elements of the story are in terms of verification or sourcing.

“Keeping communication with the teams is the key thing and that’s what came out of Hebdo,” Baker said. “As soon as a striking piece of content does emerge, make sure others on the desk who are helping you with the search are aware that this has come in and are working on it, but also trying to help the other teams.

“On the day of the Hebdo attack the other teams were desperate to run that piece of video from Jordi Mir and one thing I feel responsible for is that I didn’t necessarily communicate to everybody that we were deeply involved in the video, checking it was authentic and also considering the legal and ethical aspects of using it.”

At Sky, Baker has spent the last 10 months reflecting on how eyewitness footage and testimony can best be integrated into the reporting process with everyone aware of the needs, flows and responsibilities of the new vital field of journalism. And without a plan of action, trying to tell the story can become as chaotic and uncertain as the scene on the ground.

Check out Fergus Bell’s two-part plan for newsrooms workflows around eyewitness media.