Whether it’s the civil war in Syria, Saudi bombardment of Yemen, or protests in Egypt, the Arab world never seems to be far from the headlines.

The proliferation of camera phones across the region at a time of turmoil and unrest has seen citizen media become central to the way mainstream sources cover events in the Middle East, and being able to conduct basic research on the thousands of videos and photos emerging daily is essential for journalists working in digital newsgathering and verification.

This post, inspired by and borrowing from Aric Toler’s excellent earlier post on techniques for research on the Russian-language internet, aims to give some basic guidance if you’re just getting started on the Arabic-language internet.

Dialect dilemmas

One of the main challenges to learning Arabic is the range of dialects among the almost 300 million native speakers around the world. As a journalist doing research involving Arabic-language sources and footage, you have to be aware that the many dialects of Arabic vary greatly in their sound, grammar and even the use and meaning of words.

While this adds significant complexity to investigating Arabic-language content, it can also help: careful analysis of dialects is one way to debunk videos or to identify the origins of people speaking on audio or video.

While we’d recommend leaving this kind of analysis to native-speaking experts there are some resources to help you get a sense for how a dialect should sound. Top of the list is an amazing subreddit on Arabic dialects which features speakers from all over the region. If you have a passing knowledge of Arabic from one area you may quickly find how different dialects can be.

Transcription Tricks

Most of the time when you need to hit Google Translate it’s a straightforward task: copy, paste, translate. But what about text featured in photos or videos? The road signs? Or store fronts? Or placards held by protesters?

Unless your Arabic is مية مية (spot on) you’ll likely have a hard time fumbling through an Arabic keyboard, but thankfully Google Translate can help here too. Using the handwriting feature, if you carefully copy any script you see in a photo or video, Google Translate will try to guess the words so you can translate.

Let’s look at an example. Here’s a tweet that looks like it’s showing a protest:

Google Translating the tweet content gives us:

A quick search on Faqous Sharqia turns up a small town in Egypt’s Delta region – but is there anything in the image that can corroborate that?

Looking at one of the signs being held by a protester at the front of the crowd, we can start to see if there are any clues.

Let’s look at the word highlighted in red above.

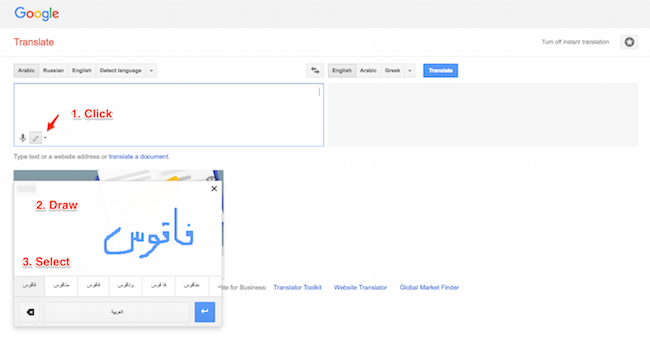

Open Google Translate and click the little pen icon in the input field. This opens another input, where you can carefully try to copy the script shown in the image. Google will try and guess the word as you go (be careful to add all the dots above and below the letters!) and based on the level of your mouse handwriting, you should get a usable result.

Downloading the Google Translate app may make life easier, as you can also use the handwriting feature there, with your actual hands, instead of a mouse.

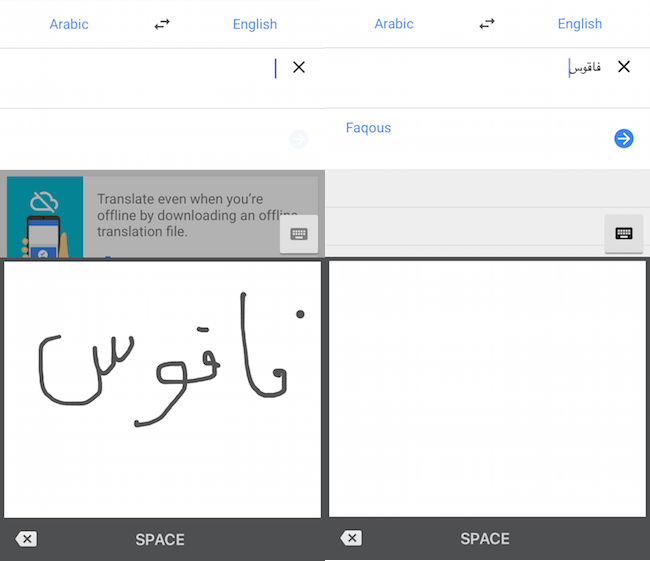

Open the app, select Arabic as the language to translate and hit the squiggle icon above the keyboard to switch to handwriting mode. Trace the shape of the script you want to translate with your finger or stylus and the app will automatically translate the writing a second or two after you have stopped writing.

In this case, the word I highlighted (as if by magic!) actually reads Faqous, the name of the town referenced in the tweet. More work needs to be done to verify the location, but this is a very useful clue.

Streetview sadface

Anyone who’s checked out some of the First Draft case studies and training resources will know how valuable Google Street View is for geolocating photos and video posted to social networks.

Unfortunately for journalists covering the Arab world, almost none of the Middle East and North Africa has been street-mapped yet, meaning we have to look elsewhere to corroborate and geolocate landmarks and features spotted in media we’re investigating.

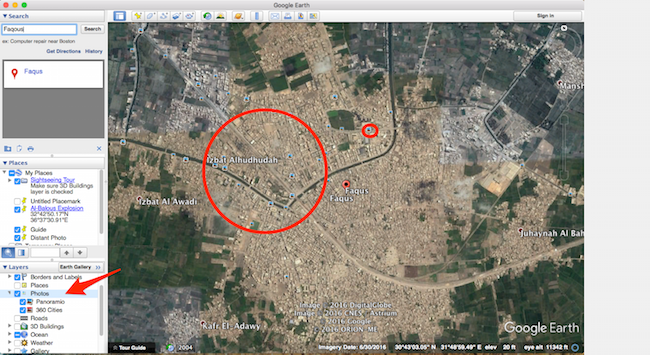

This means we have to take a more manual, research-based approach to geolocation. The good news here, however, is that in Panoramio and WikiMapia we have some excellent places to start.

Panoramio is an impressively extensive database of geotagged photos, best used as a “Layer” on Google Earth. The screenshot below shows how many geotagged photos there are available from Faqous – each of the small blue squares below is a photo or cluster of photos taken by members of the public.

These geotags aren’t always 100 percent accurate, however, so caution is advised. But the sheer quantity and range of images available via Panoramio makes it a very important source indeed.

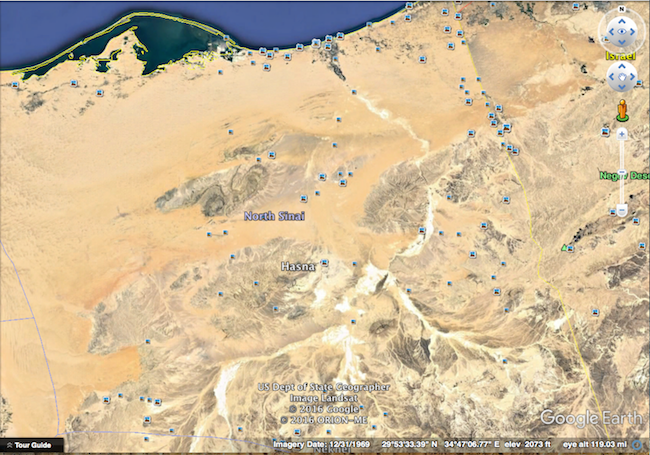

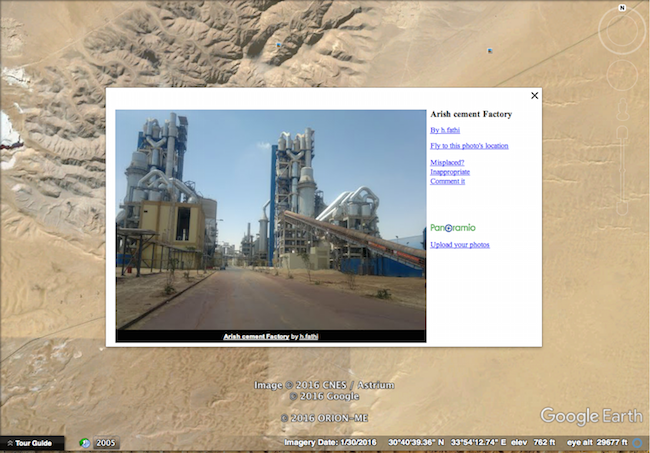

Journalists at Egyptian news site Mada Masr needed some visual corroboration when investigating an incident at a cement factory in central Sinai, quite literally the middle of a desert. The factory appeared in video clips, and reporters turned to Panoramio with little hope of turning up anything useful.

Amazingly, however, there are numerous photos of that particular factory, and the surrounding area:

WikiMapia is also helpfully detailed for some parts of the Middle East where other online maps falter.

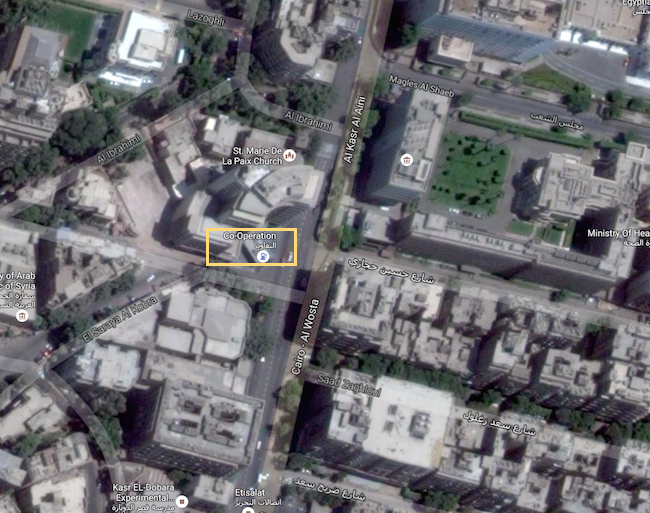

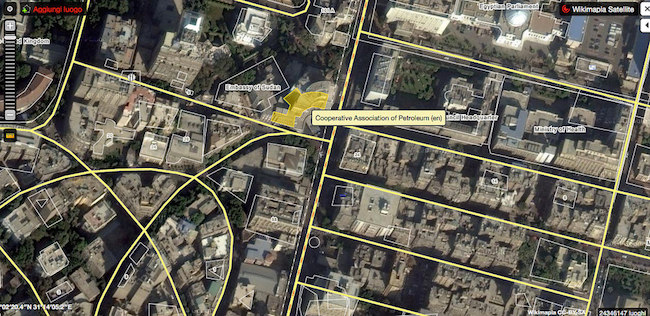

Compare the two satellite images of Cairo, below. In a famous video from the Egyptian revolution in 2011, a protestor held his ground against the force of a government water cannon. The logo for the Co-operative Association of Petroleum can be seen in the background of the footage.

When trying to pinpoint the location, Google Maps (top) only displays “Cooperation” in the place of the building. Wikimapia (bottom), however, shows the full “Cooperative Association of Petroleum” in both English and Arabic, a far more useful result in helping to geolocate the video.

Wikimapia also lets you filter results by category of locations or buildings, such as “mosque”, and often includes some additional information about a given building or landmark. As a crowdsourced mapping project there may be some inaccurate data present, but in the author’s experience the information is generally accurate.

Looking in the right places

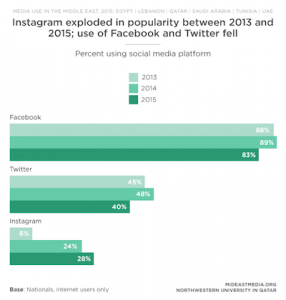

Another important consideration for researchers is knowing where to look for citizen media. While the Arab world doesn’t really have an equivalent of VKontakte, a popular social network in Russia and Eastern Europe, Facebook far outstrips Twitter in terms of users, and Instagram is growing fast.

Open-source research on Facebook is notoriously tricky, though there are interfaces emerging to navigate Facebook’s Graph Search that show promise.

Open-source research on Facebook is notoriously tricky, though there are interfaces emerging to navigate Facebook’s Graph Search that show promise.

Graph.tips and a tool from IntelTechniques.com are both very powerful, although don’t be surprised if a source is shocked – even angry – that you were able to dig up information they may have thought was private.

While the language challenges and more technical nature of researching the Arabic-language internet may seem daunting, it’s important to note the success of non-Arabic speakers in conducting important work using some of the techniques listed above, among others.

Eliot Higgins, Malachy Browne and Andy Carvin have all produced important reporting with citizen sources over the past five years.

Of course, there’s no replacement for the linguistic and cultural expertise of native Arabic speakers, and I encourage you to seek their advice and input early and often. What may take you five hours to investigate may take them a few seconds to figure out and collaboration can often bring additional benefits.

Hopefully these tips will be enough to get you started. Good luck in the investigation, or…

!حظ سعيد في التحقيق

Follow First Draft on Twitter and Facebook for the latest updates in newsgathering, verification and hoaxes.