One of the reasons Eyewitness Media Hub decided to study the impact of vicarious trauma in newsrooms and across human rights and humanitarian organisations came from a quote in our 2014 research into broadcast news outlets’ use of eyewitness media.

An experienced editor working in a newsgathering role told us : “I’ve been watching graphic footage since 1988. I don’t think there’s any difference”.

We did.

We thought there was a huge difference.

As Andy Carvin of Reported.ly said in his recent First Draft piece: “Vicarious trauma is real, and we can’t keep ignoring it”.

That was our starting point. Vicarious trauma is real. Research has shown this, most citing the work of Anthony Feinstein et al. There are many more.

What we wanted to do was build on this to understand the lie of the land. Vicarious trauma exists. One cause is repeated exposure to traumatic eyewitness media or user-generated content (UGC). Our question was: What are newsrooms doing about it?

We’ve almost completed our survey and we’re analysing the data. We reached our goal of 200 respondents and we’ve interviewed individuals working with eyewitness media in some of the world’s biggest news, human rights and humanitarian organisations. We’re starting to get a good picture of what’s going on out there. It’s a good time to showcase some of our first, preliminary findings and thoughts. These focus solely on the newsroom for now. More will come with the full publication of the research in December.

The frontline now includes the newsroom

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

“Being in the main office used to be easy and not in your face, it does feel like the frontline much more than it did ten years ago”.

This theme ran through our interviews. Many social media editors or producers are seeing a great deal of traumatic content from global conflicts. This was also visible through our survey results. 58 per cent of desk journalists working with eyewitness media saw a piece of traumatic UGC more than one time per week. With editors, this was 45 per cent.

This is not to belittle any of the horrors that international correspondents witness in the course of their assignments. It’s to elevate the role of the social media newsgatherer to someone who does witness as much horror — possibly more — as a correspondent.

This has been emphasised by many of our interviewees, from senior journalists to those just out of journalism school. As one senior newsroom editor told us: “You witness trauma a lot more with UGC. You’re exposed to more intense visual material than a battle hardened war cameramen sitting in Sarajevo in the middle of the 1990s because it’s coming at you from everywhere”.

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

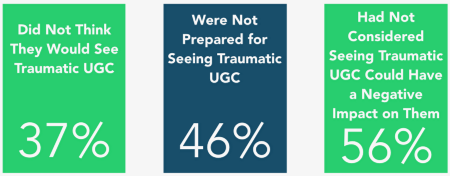

Yet many journalists entering into the social media game are not aware that they are going to be faced with such a high volume of traumatic eyewitness media.

Some 46 per cent of desk journalists were not prepared for it before starting in their role. The same group was asked if they had considered that it could have a negative impact on them. 56 per cent had not. Yet, once in their roles, 46 per cent of journalists believed that viewing traumatic eyewitness media had had a negative impact on their personal life.

So there’s a way to go — and organisations need to take this seriously.

The good news? Some are. But too many still aren’t.

The management challenge

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

The good? First of all, it’s important to note that it’s not just size that matters here. Some small, low-resourced newsrooms are doing a good job of taking care of staff who work with traumatic eyewitness media.

Yes, the larger ones are better resourced to do so and can have fancier schemes, but it’s more about managerial will than size. And that will seems to be crucial for journalists working with eyewitness media.

Is there an environment to talk about traumatic content? Is there a feeling of “will it affect my career if I admit I can’t cope with another barrel bomb video?”. This isn’t to do with the size of an organisation. It’s got nothing to do with the number of people working on a desk. It’s simply managerial culture.

This was emphasised by one senior newsroom manager: “There’s the question of ‘will admitting to being traumatised have an impact on my career?’ Because it doesn’t have an impact on your career, but people think it will do, so just breaking that is important, and it rather depends on who your manager is”.

This fear was iterated by a social media journalist experiencing exactly that same problem with their manager: “I feel like I cannot say ‘no’ to looking at horrific UGC because I want to do well in my career and I can only do that if I say yes to everything.”

And when the manager is careful about these things?

“This is the nicest newsroom I have been in by a long way,” said one respondent. “Other organizations I worked for made me feel like it would be a sign of weakness to admit that I wasn’t coping. I feel totally comfortable talking to our boss.

“A number of managers check in with us from time to time and ask if we are drinking too much, eating too much, kicking the cat or whatever and that shows that they are very aware of the impact that this stuff can have on us which I think is really supportive.”

So it is possible to run a newsroom and ensure the team gathering and publishing content sourced through social media are okay. It depends on will.

Surprise can be the champion of horror

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

Away from that managerial culture, there’s also the question of building workflows in newsrooms that take the risk of vicarious trauma into account.

What do I mean? In our interviews, time and time again journalists told us that they are more impacted by traumatic eyewitness media that they are not ready to see than content that they are prepared for.

“For me the major thing is the lack of warning you get for what you are going to see.”, said one. Another noted that when they started “that was one of the difficulties — getting hit by traumatic material without knowing what was coming, it’s arousing physically and makes your heart race and that’s when you realise that this is not good for you”.

So, if your newsroom is putting traumatic video onto a server without labelling it as such, or you’re in the habit of saying to a colleague “hey, look at this” without thinking about it — maybe you and your newsroom need to be re-evaluating your workflows with trauma prevention in mind.

This also applies to newsrooms which are experimenting with new newsgathering techniques. Messaging apps, such as WhatsApp, seem to remove some inhibitions around sharing content — with the result that a journalist using closed tools to find exclusive content can, without context, be confronted with horrendous imagery they, again, are not steeled to see.

Developing individual coping mechanisms

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

Several journalists and editors who had been working with social media for a long time (in this world that’s over four years), who were at the vanguard of using eyewitness media to tell stories, spoke of how they had developed their own coping mechanisms.

These ranged from viewing Tumblrs of cute dogs doing silly things, to Taylor Swift’s Instagram feed to walks outside or increased exercise. Journalists and managers alike should be aware of the need for this — and allow individuals to develop ways that work for them.

Newsrooms are moving in the right direction

What has been reassuring in this study, however, is that, in the news sphere, not one journalist spoke of vicarious trauma not being an issue. In just 18 months there has been a shift from a world where there was denial among senior management, to a world where many newsrooms and their management are trying to take care of their teams who are using eyewitness media to improve their storytelling. One newsroom is even reportedly introducing a meditation room in its new offices.

So much more to come…

These are just some of our preliminary findings, of course — and there is so much more to write about. In our final publications we’ll also look at what institutionally-provided resources help the most, the importance of building mental resilience and the stigma around mental health in general.

We’ll be publishing our full findings in December at events in London (December 10th) and New York (December 14th). If you’re interested in attending one of these events, or are interested in talking about this research, please drop a line to sam@emhub.co.