Back in November we wrote about the preliminary findings of our research into vicarious trauma in the newsroom. In that piece, we illustrated how vicarious trauma is an issue which newsrooms and their managers need to start taking seriously when they have journalists who use newsworthy photographs or videos captured on smartphones by people around the world. That journalists were scared about admitting to their managers that they are having a hard time dealing with some of the more distressing images they see day in, day out.

We’ve now published the full findings of the report – “Making Secondary Trauma a Primary Issue: A Study of Eyewitness Media and Vicarious Trauma on the Digital Frontline“. In the report we call on the management of news organisations to provide training for journalists as a matter of course – in the same way they now provide hostile environment training.

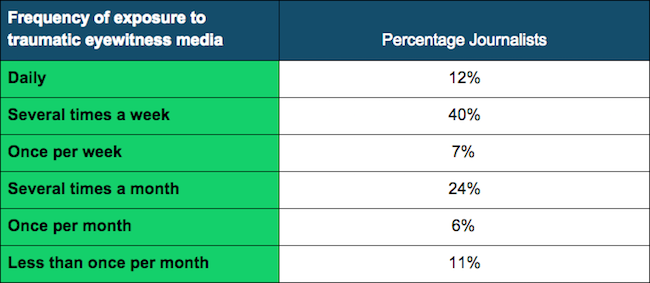

Why do we make this call? Because the results show just how much traumatic content journalists working with social media are seeing. Over half of the journalists surveyed are viewing distressing eyewitness media several times a week.

The frequency of exposure to graphic images can have a serious impact on journalists

Furthermore, in our interviews, those journalists who worked at organisations that did acknowledge viewing distressing imagery at headquarters was an issue for their staff spoke more highly of their organisation. Those working for organisations that did not see it as an issue spoke of colleagues who had been signed off sick through stress or who had even resigned from successful careers. Not acknowledging this is becoming a human resources issue.

But changing organisations is a big challenge, and it’s an issue we’ll be working on at Eyewitness Media Hub as we move forward. Our goal is to build coalitions of organisations which care about this issue to share best practices and build awareness. It’s one of our biggest goals of 2016.

Here, however, we want to focus on some of the tips we gleaned from talking to journalists who work regularly with eyewitness media and view traumatic content, and answer the question of: “I work on the digital frontline, I’ve just seen a lot of distressing content, how can I protect myself?”

1. Limit your exposure to sound

One social media journalist told us: “Sound makes the impact more real”. This was an issue we heard again and again when speaking to journalists working on the digital frontline. People spoke of the horrific imagery they’d seen, but noted that hearing the violence or people screaming in agony or to save their lives made the distress they experienced more acute.

“Usually I watch the video without sound after I hear it once, because then I know if there’s anything relevant in there or not,” one person told us. “Then I always turn it off for that specific reason that it always makes it rougher to watch.”

Another emphasised how: “When I click on some links, I have the headphones off my ears, I have the audio on low.”

When viewing eyewitness media you think could be traumatic or distressing, consider only listening to the audio if it’s truly necessary.

2. Surprise makes viewing horrific imagery more traumatic

“Unexpected things make it harder. If you know what to expect – blood, killings – it’s not easy to watch of course, but if you know what’s coming it makes it a bit better.”

Frequently journalists told us about the difficulty of viewing traumatic content that they weren’t ready to see. The problem is exacerbated by contemporary workflows in newsrooms which mean each and every person working in a newsroom has access to each and every picture. Newsgathering through social media means that somebody is going to see distressing images that they weren’t prepared to see – but workflows should mean that the surprise doesn’t spread from there.

Ensure graphic content is labelled as such when put on a newsroom server, and if you’re sharing content with colleagues tell them they may find it distressing before they see it.

3. Managers, help people to feel comfortable talking about the impact of graphic images

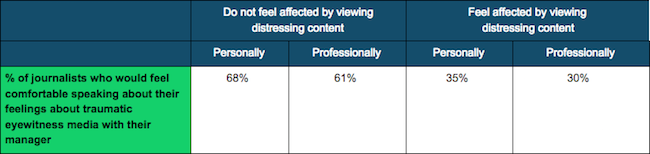

Our research showed how people who have been distressed by seeing traumatic content are less likely to say they would talk about it with their peers or managers than those who have not.

Journalists need to be open and feel able to talk about the effects of graphic images if they are to cope with it effectively

Of those journalists surveyed, 35 percent who felt they had been affected in their personal lives by viewing distressing content said they would feel comfortable talking about it to their manager. This rose to 68 percent for those who did not feel they had been affected.

In our interviews, journalists who worked in organisations where their managers and workplace culture were conducive to speaking about the traumatic impact of viewing distressing content spoke more highly of their organisation. One manager summed up their approach to leading a team which frequently looks at traumatic imagery: “I blub by example, as it were. If somebody realises you’re impacted by it, it might make you feel more approachable.”

Work on building a workplace culture where people feel comfortable in speaking about the effect of viewing traumatic imagery.

4. Only work with traumatic content if it’s going to be used

One journalist we interviewed told us: “You don’t come to journalism for money, you come to journalism to tell stories, to make a difference, to have an impact. If you feel you are not making a difference, that’s actually going to affect you considerably.”

Verification is a long manual process that can mean going through a video frame by frame. This can be particularly burdensome and distressing if this is a video that shows a traumatic event. As another journalist told us: “I feel more depressed when I go through a lot of UGC and it is not used.”

Only ask a social media specialist to find or verify content of a traumatic event if it’s actually going to be used in your storytelling.

5. Find coping mechanisms which work for you

Interviewees detailed the varied mechanisms they used to cope after viewing distressing eyewitness media.

While in the office, these included: “Keeping open a [browser] window showing a Tumblr feeds of cute dogs” , “Checking out Taylor Swift’s Instagram feed”, “Getting out of the office for a walk and a chat to a friend”. The coping mechanisms were varied – but worked for the individual interviewee.

Different coping mechanisms work for different people. Journalists should think about what works for them and managers should understand and support them.

We’re sure that others have other tips which work for them when using distressing eyewitness media. Share them with us.