As Moscow prepared for protests by Russia’s political opposition last month, a search of the “Red Square” geotag on Instagram revealed a peculiar sight: a wall of uncanny human faces, maybe too symmetrical to be real. This offered a clue as to one of the novel techniques possibly being used to stifle dissent, push pro-Kremlin narratives and disrupt organic Russian-language online conversations.

In the past year, much of the disinformation seen in online Russian-language spaces directly or indirectly targeted the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) and its founder, Alexei Navalny. He was sentenced in late January to 3 1/2 years in prison upon his return from Germany, where he was recovering from Novichok poisoning linked to Russian operatives. And a new wave of suspicious online activity has emerged alongside the protest campaign kicked off by Navalny’s return and subsequent arrest.

This fact sheet explores some of the noteworthy online behaviors seen around the recent protests, which in some cases resemble familiar disinformation tactics and in others may point to emerging disruptive methods.

Young influencers asked to advance anti-opposition talking points on social media

Over the past decade, figures in or affiliated with the Russian government have been known to buy popular Telegram channels, allowing them to target the channel’s followers with pro-Kremlin narratives and false claims about the opposition.

But in recent weeks, similar cases emerged on Instagram and TikTok — a platform virtually unknown to most Russian social media users just two years ago that in 2020 became one of the most-downloaded apps in the country. Amid the January protests, Russian TikTokers such as Boris Kantorovich reported being approached with requests to promote negative messages about Navalny and FBK in exchange for payment starting at 1,000 rubles (about $13.50), with higher payments for those with more followers.

Those who accepted the job were contacted via Telegram and sent a document, received and shared by Kantorovich, outlining talking points. Account holders were asked to say they were “tired of all this hype around Navalny,” that “children are being dragged [into the protests]” and that “they are provoking the police,” with a separate instruction that the talking points were to be paraphrased, not used verbatim.

Kantorovich, it appears, never had any intention of following through. “Received the task memo, unfortunately won’t be able to get it done in 30 minutes today,” he noted sarcastically in a tweet. He also shared a thread detailing the TikTok creators who accepted the offer.

State-linked groups staged ‘organic’ events, amplified online

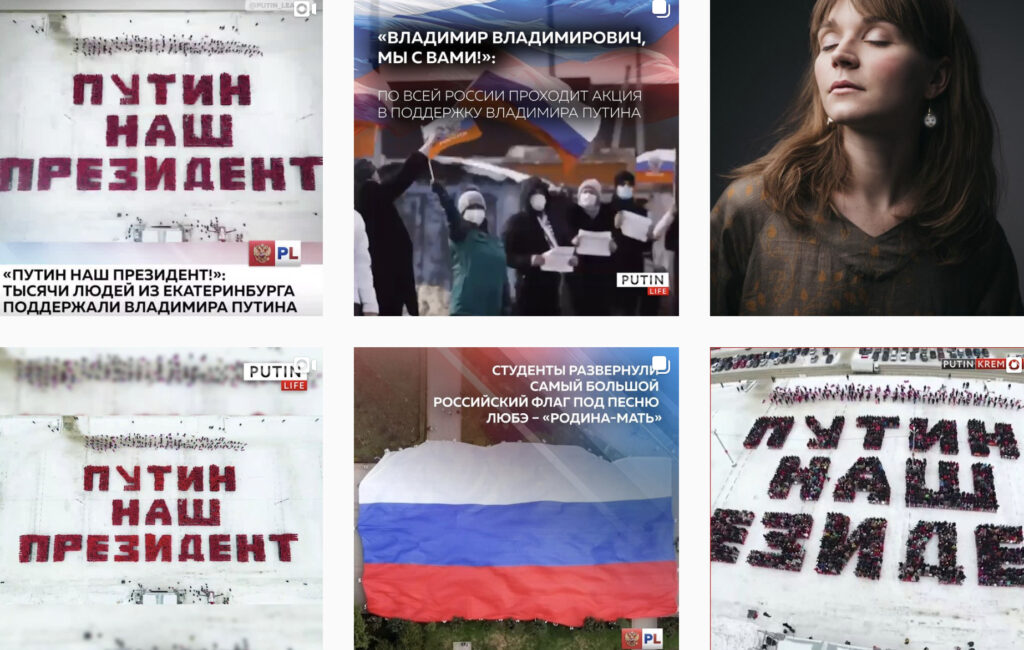

Deceptive tactics are also used to organize — and later publicize online — offline events that ostensibly show support for the government of President Vladimir Putin. These purportedly spontaneous “flash mobs” (often arranged under the stewardship of state-affiliated youth organizations), where participants wave the Russian flag and chant “Putin is our president,” are clipped together into viral videos shared extensively on VK, Instagram and other social media.

Multiple Instagram accounts published similar videos of the pro-Putin “flashmobs.” Image: Instagram, screenshot

After one such video, with an overdubbed pro-Putin chant, featured in an Instagram post of a local politician in Belgorod, the students seen singing and marching in the video complained to their university administrator for involving them. The students had been told their performance would be part of a music video. Claiming that she was carrying out a “social service contract,” she apologized for misleading them and resigned.

Another example saw a group of schoolchildren — members of the government-run Russian Schoolchildren Movement — use drones to write the message “Defend The Veterans” in the sky. This was in reference to the ongoing trial of Navalny, who is accused of the “slander” of a war veteran. The video was promptly amplified by pro-Kremlin social media accounts, including NTV, a station owned by a branch of Russia’s state-controlled energy giant Gazprom. The Kremlin has denied its involvement in this and similar campaigns.

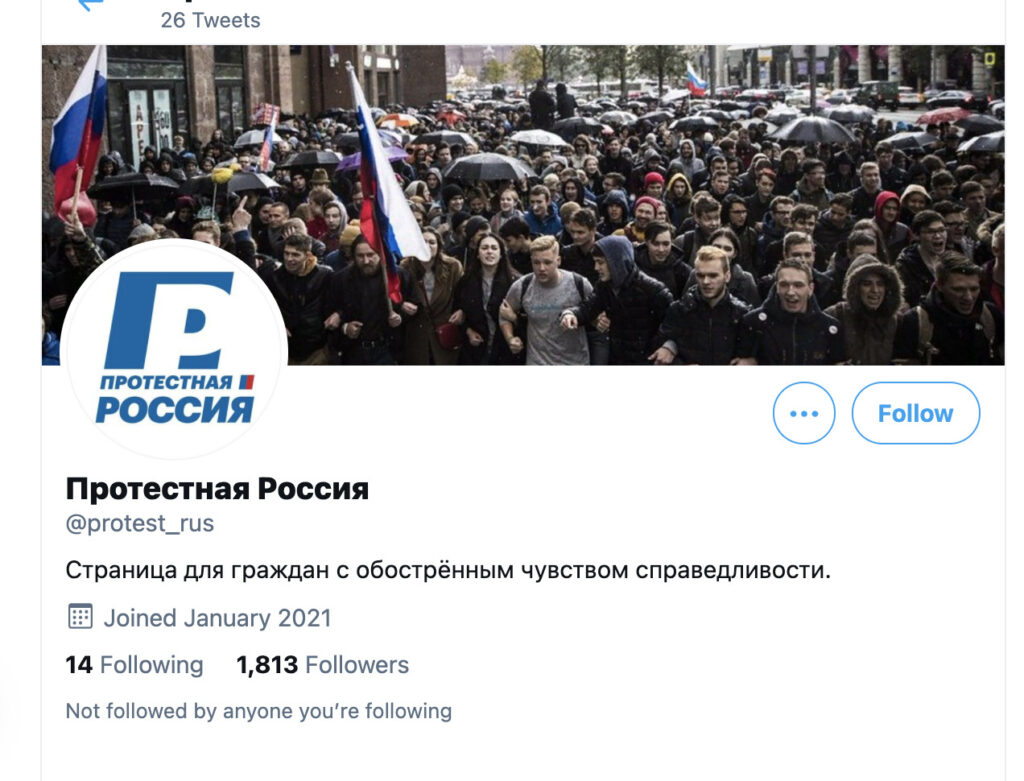

Imposter accounts shared protest misinformation

Some accounts that appear sympathetic to the protesters are being used in ways that could disrupt them. In one example, Twitter and Instagram accounts posing as Navalny’s mother, Lyudmila Navalnaya, emerged. The Twitter account quickly drew nearly 2,000 followers. But after activists reached out to her son, Oleg Navalny, and confirmed that those accounts did not belong to her, the Twitter page was rebranded as a generic pro-protest account. It was subsequently used to share broad messages of support for the protesters, but also misinformation, namely a tweet claiming a protest was scheduled for January 30. The real protest was the day after.

An account initially posing as Lyudmila Navalnaya was exposed as fake and promptly “rebranded” into “Protest Russia.” Image: Twitter, screenshot

In a similar case, an account posing as legendary Russian actress Liya Akhedzhakova — known for her sympathy to Russia’s opposition — was also determined to be fake and deleted days after its creation, but not before gathering more than 30,000 followers.

It’s unclear who is behind the imposter accounts. But similar tactics have been employed by Russian and other state-affiliated actors to foment division in US and European politics, in some cases by mixing facts and fabrications.

An emerging AI technology was used to game Instagram’s location filter

On January 17, the day of Navalny’s return from Germany, Instagram users in Russia began seeing certain hashtags and locations flooded with dozens of photos of “human” faces. The faces bore the hallmarks of an artificial intelligence method called a generative adversarial network (GAN), which can create fake faces to substitute for easily traced photos of real people. The accounts with GAN-generated faces crowded out the authentic posts from the Red Square location on Instagram.

This “geotag squatting” tactic may have been used again on the eve of the protest, when the Instagram location for Moscow’s iconic plaza was filled with posts like this one by accounts bearing images of Navalny. The posts called for the opposition to rally, but failed to specify the time or location of the protest. Some pointed out that Red Square was cordoned off and filled with police officers that evening, suggesting that the activity may have been an attempt to siphon off attendees from their original destination, the Pushkinskaya Square, leading them to a heavily policed area instead.

The use of neural networks to generate profile images is a relatively new way to spread disinformation. For now, investigators can spot the telltale signs of accounts using GAN images, such as distorted backgrounds and unnaturally uniform eye placement, but as the technology advances, spotting fakes will surely become more difficult.

The recent proliferation of fake profiles seen in Russia hasn’t been directly attributed to any state actor. However, it resembles a method used by PeaceData, an influence campaign by the Russian government-linked Internet Research Agency that was exposed by social media platforms and FBI investigators in September. A news website operated by that campaign used algorithmically generated images of fake “editors.”

Instagram’s safety features appear to have been weaponized against some protesters

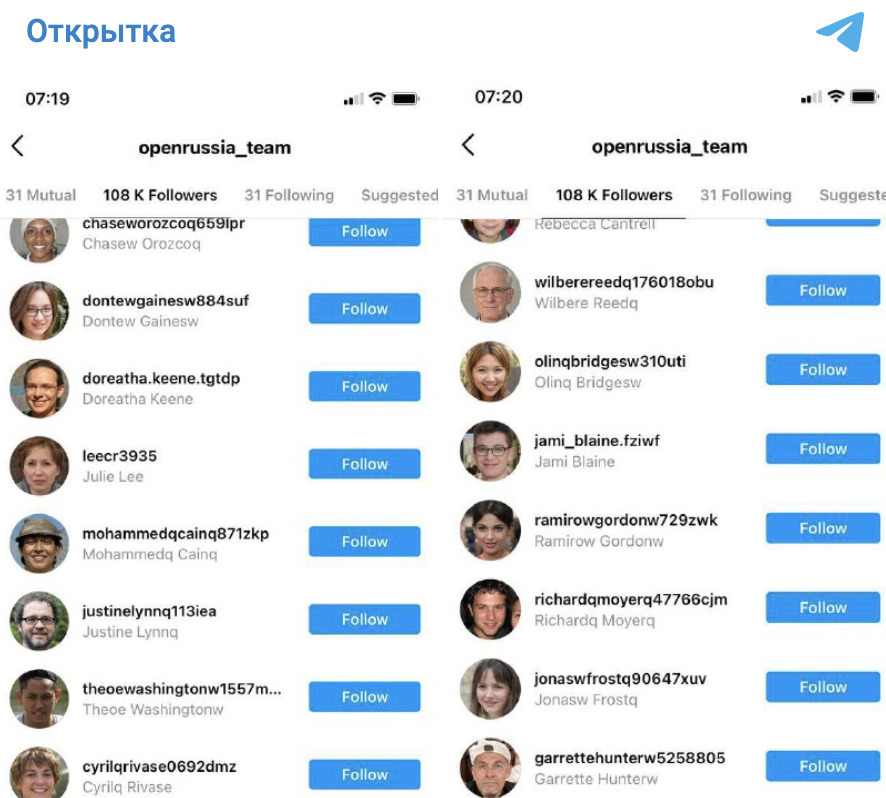

While the original purpose of the flood of suspicious accounts is unclear, in the days after Navalny’s return a number of Russian opposition activists reported a spike in Instagram followers, many exhibiting familiar indicators of inauthenticity. It is difficult to say how much overlap there was with the accounts tagging Red Square with AI-generated faces days earlier. But they shared revealing features besides the GAN profile pictures, including very recent registration dates, account handles that appeared randomly generated, and little or no organic content or engagement.

An influx of suspicious accounts followed prominent Russian opposition activists and organizations. Image: Telegram, screenshot

Independent social media observers and watchdogs speculated about the accounts’ potential purpose. One theory was that the behavior would trigger automated bans or suspensions by Instagram, either through these new followers mass-reporting the activists’ accounts, or because the sudden influx of inauthentic followers would raise red flags.

Deliberate triggering of account bans is now widespread enough that businesses offer such services for a price. Some of the users targeted were forced to make their accounts private; at least one opposition figure who was targeted also received a note from Twitter warning that complaints were filed about her account for signs of “self harm.”

While there is so far no conclusive evidence that Russian authorities or government-linked organizations played a part in this campaign, it shows that actors aiming to disrupt protest activity are astute enough to adapt their tactics to changes in social media usage. These actions also expose weaknesses in the platforms and demonstrate ways of “gaming the system,” including the very features developed to protect it from abuse.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.