Since Myanmar’s democratically elected government was ousted February 1, social media has been inundated with conspiracy theories and rumors.

In this case study, we explore a recent theory that emerged when people in Myanmar noticed Chinese characters appearing on their mobile devices.

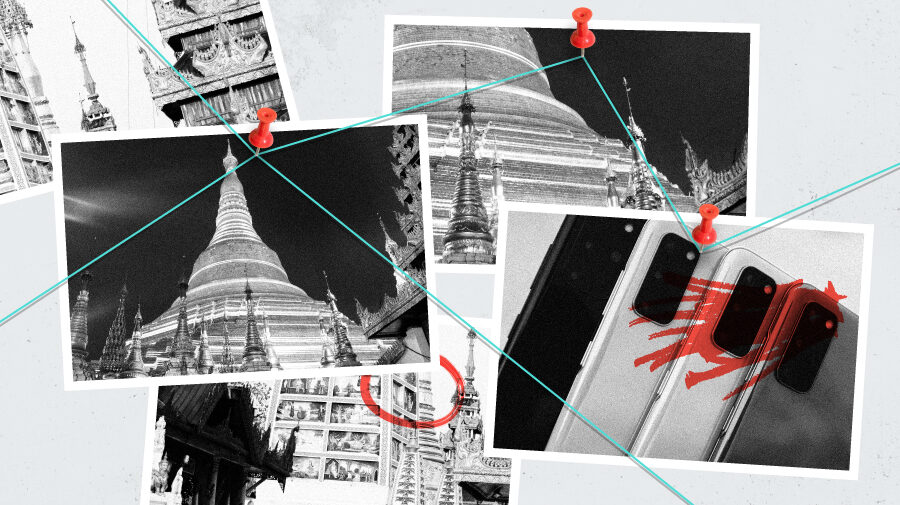

Myanmar’s military junta announced on February 11 plans to introduce sweeping new cybersecurity laws that would give authorities what Reuters called “unprecedented censorship powers,” less than a fortnight after it overthrew Aung San Suu Kyi’s government. The proposed laws led to speculation online and among protesters that Chinese IT equipment and technicians were being flown in to help implement an internet firewall, similar to the Great Firewall of China.

The junta has denied this, but fear over alleged Chinese support for the military coup was exacerbated when social media, particularly Twitter, erupted with claims that Chinese characters were appearing, seemingly at random, on mobile devices, smart TVs and apps following the announcement of the new cybersecurity laws.

These rumors have since been debunked by internet monitoring firms and analysts, who said the characters’ appearance was the result of a technical glitch.

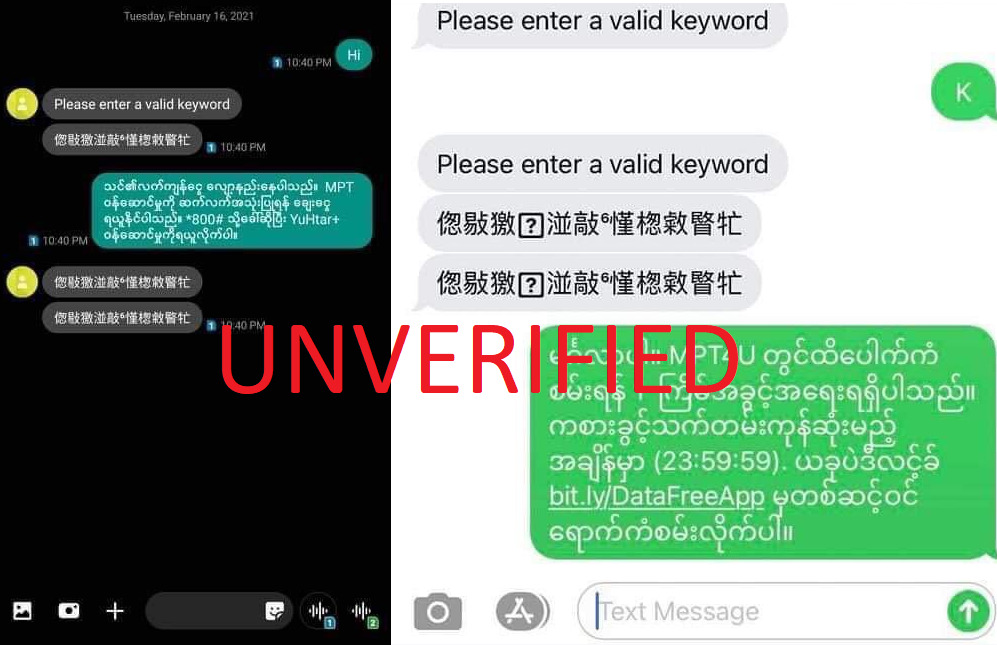

Starting on February 17, people in Myanmar reported they were receiving automated messages from telecommunicators operators in Chinese, rather than Burmese, language. On the surface, the Chinese-language messages are gibberish, and the string of characters appears to be identical across many different screenshots and videos shared by internet users.

In reference to the strange characters, social media users made comments such as “China is definitely involved in Myanmar military coup” and “This may be because of the great firewall of china.”

Around the same time the Chinese characters were appearing on mobile devices, smart TVs across Myanmar started displaying Chinese characters on their menus and on apps such as YouTube. This, too, prompted people to claim foreign interference.

“This is obvious that China is helping Myanmar military to strictly control/monitor telecommunication,” one Twitter user said.

The issue attracted international media attention. BBC’s Freya Cole tweeted on February 16, “There is huge concern about CCP involvement in Myanmar. But it’s difficult to verify. I need telecom workers & airport staff to securely speak to me. I also need way more evidence. If you notice Chinese language on your phone or TVs pls screenshot. Inbox me.”

A BBC journalist shared images of the Chinese-language text seen by mobile customers in Myanmar. Image: Twitter, screenshot

An investigation by Hong Kong-based independent news outlet Citizen News found that the Chinese characters were likely the result of an encoding issue within the telecom providers’ system. Plugging the Chinese-language SMS text into a tool used to decode UTF-8, the character encoding method most commonly used on the internet, returns the message, “Please enter a valid keyword.” You can even reverse engineer it using a character encoder/decoder tool.

An analysis by the monitoring service Netblocks also found that the Chinese characters were a side effect of the new internet restrictions, which affected the functioning of Google servers. A similar issue occurred in June 2020, when Verizon customers reported receiving nonsensical messages in Chinese. The problem was that messages were being sent in UTF-8 encoding, but were decoded in the more complex UTF-16BE.

While the BBC’s Cole later clarified that the characters were not an indication of Chinese government involvement, social media users discussing Myanmar quickly circulated her original post on Facebook and Twitter as validation of their concerns, urging others to send Cole evidence so the alleged collusion could be exposed. In the case of Cole’s tweet, the use of social media for journalistic inquiry inadvertently became a mechanism for the spread of a conspiracy theory.

Amid the larger questions about China’s relationship with Myanmar, the technical errors that resulted in Chinese characters being shown on digital devices became one node in a larger complex of conspiracy theories. The theory about the characters was used to support larger conspiracy narratives which, at the moment, remain far from proven: the idea that a China-style web surveillance regime was being set up in Myanmar; and that China was involved in the military coup there.

The example of the Chinese characters demonstrates how a volatile situation such as Myanmar’s can fuel conspiracy theories, which draw on a lack of trust in authorities. With a knowledge deficit created by Myanmar and China’s opaque politics and relations, speculation and rumors continue to run rampant.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.