This past weekend, First Draft co-hosted MisinfoCon, along with Hacks/Hackers and Nieman. It was a summit and creative studio on misinformation, at MIT Media Lab. Nieman has done a great job summarizing the event but I wanted to share my own experience of the event as a participant.

Breakout Sessions

Saturday started with a dozen or so breakout sessions on topics such as: how to enable readers to look “under the hood” of investigations, how to make vetting information easier for readers and how to tackle the influence of people’s fear on how they process the truth.

I headed to the “Librarians and the Public Need for Education on Media/Information/Data Literacy” session because I’m interested to see how librarians might help us build solutions for public education and news literacy. I wasn’t disappointed.

Jason Griffey, a librarian technologist and fellow at Berkman Klein center at Harvard, led the discussion. He talked about how libraries and librarians can leverage their positions as trusted sources to promote issues that strengthen the community without tarnishing their non-partisan reputations.

Librarians have a rebel streak that few people see, said one librarian from the Washington D.C. area. “They think we’re all books and ‘shhhhh.'”

The four librarians in our group spoke with pride about holding the public trust and said clearly that they do not want to get involved in the fact checking business. Instead, they see themselves as conduits to help others find reliable and trustworthy information.

Group Projects

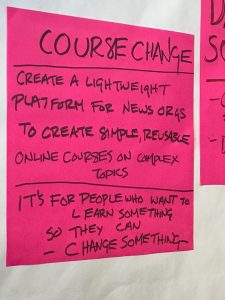

One project idea.

Photo: Steve Rosenbaum

After the breakout sessions, people were invited to write their ideas to clean up the misinformation ecosystem on giant post-it notes. I was interested in a pitch to share an analytics base between newsrooms, but then this group started talking with Gregory Maus from Indiana University (Hoaxy) about sharing research and the groups combined.

In our group, we had a data scientist, two developers, a researcher and me (journalism background). We talked for the first 90 minutes about creating a platform where journalists can connect with developers. We started wireframing a website and then someone asked if anyone else is doing anything in this space. One web search revealed Mozilla’s OpenNews.

At this point, one of the developers left to join another group.

We changed tracks and started talking about how much research is already done about the misinformation ecosystem, but the problem is that it’s done in different disciplines and the information doesn’t travel between siloes. Worse, when the research is done, it’s not presented in a way that’s easily understood by journalists who can amplify the findings to the public. Is anyone else doing something in this space? A web search revealed theconversation.com. I was losing heart in our ability to arrive at a fresh, substantive idea.

Our own Claire Wardle came over to our group and asked how our project was coming along. I confessed I was just about to leave the group. Then Abigail Stiers, a software developer from Maine, synthesized the idea: we want a platform that distills research from all disciplines and makes it easy to understand for everyone, especially journalists. We want to put researchers, journalists and developers in touch with one another, and create a community where they can ask a clumsy question and learn the vocabulary to ask for what they want and developers can discover what is needed.

From left: me, Abigail, Dean & Gregory.

Photo: Philip Smith

I sat back down. Claire teased out more from Abigail and within five minutes, our group was on track toward a solution that connects academics and journalists who then might inform the public and policy makers.

Dean Jackson, a researcher at the National Endowment for Democracy, returned from a walk and announced the name for our project: Pheme. I showed him that First Draft Partner Network member Pheme project already used the name. Within an hour, Dean made another suggestion, Candelabra, as it offers light from many sources. Abigail and I said, “I don’t hate it,” so that’s the name we settled on for our project.

The Candelabra group has agreed to meet twice monthly on video conference to flesh out the plan, seek guidance, and eventually funding, to create the platform.

Twenty projects emerged from MisinfoCon. I don’t know if any of these ideas will be the breakthrough to upend misinformation, but I am relieved that so many people are engaged in trying.

Weekend Takeaways

- There is no one solution to solve misinformation.

- A broad range of skill sets and expertise will be required to solve misinformation.

Weekend Highlights

- From Alexandra Samuel: As First Draft’s Claire Wardle pointed out in her very helpful overview of the misinformation ecosystem, fake news doesn’t just come in the form of text. Images — like those ubiquitous social media memes — can be a powerful way of transmitting false information. Social media loves images, so once information is embedded in a shareable image, it spreads quickly and may be readily accepted as truth.

- Watch Claire’s lightning talk about the Tuesday launch of CrossCheck

- Other lightning talks.