With the arrival of Russian bombs in Syrian towns and villages it’s worth taking a look at the most effective ways to explore Syrian social media and some of the verification challenges faced when covering both Russia and Syria.

The first key thing to appreciate about the use of social media in Syria is that in most opposition held towns there’s extremely limited internet access, with satellite phones providing a link to the outside world.

This means that over the four years of conflict in Syria the opposition groups and local media centres have come to use a small number of social media accounts. So, for example, each town or opposition group might have a YouTube channel, Twitter account, and Facebook page, and that will represent the majority of information you’ll be able to discover from those locations from social media.

While this limits potential sources it also means you can create lists of these accounts which you can keep an eye on for what will represent the majority of information coming from areas attacked. With Twitter you can create Twitter lists, and with YouTube you can subscribe to channels you discover.

This raises two questions. First, how do we find these channels, and second, how do we know which are the original sources of the videos?

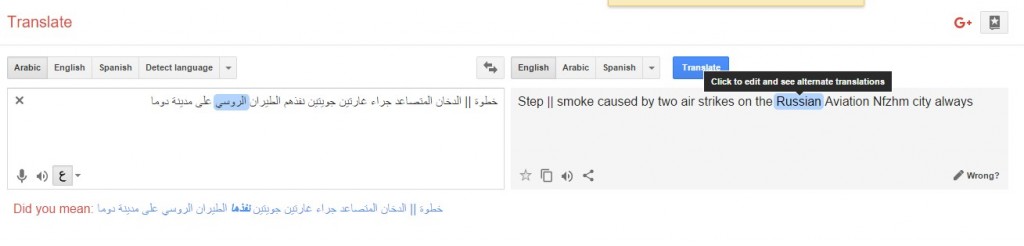

There’s a number of ways to find channels. If you’re watching Twitter and Facebook you’ll likely see videos shared online from various locations, and then it’s a matter of just looking at the channel they’re posted on. You can also do keyword searches on YouTube, but what if you don’t know Arabic? One useful trick is to first find video with a title containing the word you’re interested in, then pasting it into Google Translate. Then, in the translated text, hover the mouse cursor over the word you’re interested, and you’ll see it highlighted in the Arabic text, as shown below:

Then simply copy and paste the word into YouTube search. It’s best to limit searches to the last month as there’s four years’ worth of videos from Syria — and over 1 million when reuploads are counted — so searching for something like a town name or a word like “bombing” will bring up a lot of results.

But how do you know which channels you should be following? Generally you’re looking for channels that are the original sources of videos, and in Syria they’ll often be named after the town their based in or the armed opposition group which they belong to.

For example, the “talbisa h” channel covers the town of Talbisah in Homs, recently bombed by the Russian air force. Most channels also have their own logos which are generally in the top left or right corner of the videos uploaded to their channels, and are visible on the video listings, as shown below:

If you find a channel which has lots of videos with different logos then it’s almost certain these are not original copies of the videos. However, some channels will upload videos with a few different logos, or animated logos that might switch between a FSA flag to the channels logo, so be aware of that when examining channels.

You’ll also find most videos posted on channels will have dates and locations included in the titles, so if you see sequential dates and the same locations mentioned repeatedly there’s a very strong possibility these are original uploads.

But what if you find a channel that has videos that appear to be from other channels, what can you do to find the original? Some videos are reuploaded with the same titles, so a quick search on YouTube can get results.

As most are uploaded with locations mentioned in the titles searching the name of the location from the title can find other versions of the videos and other channels that are from the same area. Doing a reverse image search on the preview image for the video may also bring up matches. If you know Arabic it can be simply a case of reading the logo on the video and searching for any related terms.

Discovering channels on YouTube can also lead to the discovery of other social media accounts. Always check the About page on any YouTube channel as that can often list all the social media accounts used by the same group. The same goes for the descriptions of each video, you’ll often find they copy and paste their social media accounts into every description. On Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter you can also check out the accounts they follow to discover other social media accounts.

With a bit of work you’ll soon find you have a set of social media accounts that can provide the most current information from the ground. As with all open source investigative work verification plays a key role, and other First Draft articles cover the various tools and methodologies that can be used.

Because we know Syrian opposition groups use social media in a very particular way we can also make judgements about the reliability of certain videos. If you see a video being shared on a social media account that is new or doesn’t seem to be related to a town or group then that should immediately ring alarm bells.

A good example from the recent bombing in Syria is this video, claiming to show a Russian jet hit by a MANPADS surface to air missile:

By Murad Gamzayev on YouTube

The issues here are that it’s posted to a channel that’s barely been active, and the title is in English, which is extremely rare for videos from Syria. Unless you can find an earlier version of this video on a channel that is used by an opposition group you should not even begin to think this is a reliable video.

All of this should give you enough to get started discovering useful content on Syrian social media, but be sure to check out other guides on First Draft for further investigative methods and verification techniques.