Did a passenger film the terrifying moment turbulence struck a flight from Florida to Italy in January? Did Daesh gun down 200 children in a mass execution? Did a Syrian boy save a girl from under a hail of bullets? Did a golden eagle swoop in to carry a young child away from his family in a park in Montreal?

The answer to all these questions is no, despite video footage claiming to show the events as real. This didn’t stop multiple news organisations publishing the videos as true, however. Despite advances in verification tools and techniques, spotting fake videos is still a particularly difficult nut to crack.

Misinformation in pictures or video generally takes three forms on the social web: footage is either purported to relate to a different time or place to when it was originally captured; has been digitally manipulated between capture and publication; or has been staged.

“There are many different cases,” says Dr Vasilis Mezaris, senior researcher at the Center for Research and Technology Hellas (CERTH) in Thessaloniki, Greece. “And what’s interesting is there are many different types of deceit or potential deceit, so there are many different problems to be addressed.”

With CERTH, Mezarlis is leading a new consortium of technology companies, universities and news organisations, funded by the European Commission, in search of a missing component of content verification in news: tools to verify video.

“It’s not just about finding if a video file has been manipulated and processed, as in the eagle hoax,” he said of the project, dubbed InVid for ‘in video veritas. “It’s also about finding out if a video is consistent with the information that accompanies it or if something has been re-used, which is a very frequent occurrence.”

That turbulence footage used by news organisations for a flight in January was from 2014. The footage of Daesh “executing 200 children” was also from 2014. The video of a Syrian hero boy was staged by a Norwegian production company and the Montreal golden eagle video was a digital fabrication.

Resources exist to analyse videos but largely rely on technique, experience and a healthy skepticism rather than technological solutions. By comparison, spotting pictures that have been repurposed for a breaking story is relatively easy.

A reverse image search of a picture purporting to be from a news event with Google, TinEye, Yandex or other image databases takes seconds and is generally accurate enough to be reliable. Such tools to help verify images abound as the process only needs to apply to one image, rather than analysing 24 images for every second of a video in question.

Reverse video searches are not impossible, but to take every frame in a single video and cross-reference it with every frame in every video on YouTube, for example, would require exceptional levels of computing power. Add the fact that 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute (that’s more than 43 million frames per minute, in case you were wondering) and we’re quickly in need of a quantum computer to crunch the numbers and find a match.

So, at present, the next best bet is to take a screenshot of a video’s thumbnail and use that as the basis for a reverse image search. Site specific searches like “site:youtube.com” and relevant keywords can be added to narrow the results further. But as any journalist will attest, tracking down an original video can be frustratingly slow and inaccurate, assuming one even exists. It’s like hoping to find a needle in a hundred-acre farm.

“With InVid we decided from the beginning that we wanted to focus on video,” said Mezarlis, and approach the issue from every angle, from duplicates to doctored footage. “So looking at things like video analysis, as a first stage to understand the structure of the videos and index them appropriately, and then look into the forensic analysis of video files.

“This is one very important aspect. It will essentially allow us to provide tools that will help the user to understand if some video footage is the way it is shot or if it has been post-processed and manipulated in some way.”

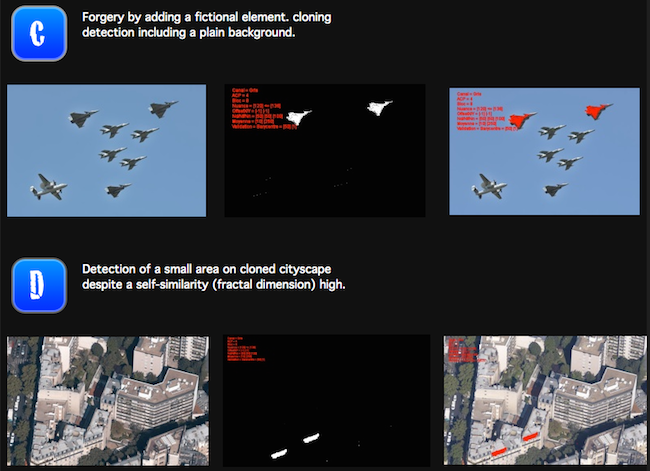

Enter Exo Makina, a firm commissioned by the French Ministry of Defense in 2009 to build image verification technology and member of the InVid consortium. Their solution was Tungsten, which analyses the digital nature of image files on a range of levels, detecting alterations or anomalies which may be the result of manipulation.

How Tungsten detects cloning in images. Screenshot from Exo Makina

French security forces, government ministries and a number of news organisations now use Tungsten to detect fake images, and Exo Makina founder Roger Cozien intends to build an extension to the software devoted to video verification.

“We first need to understand how a digital video is made from a signal processing point of view,” he told First Draft, via email. “Then we shall write a generic mathematical model of such a signal with a view to understanding what may be the reasons of any deviation in this model.”

The details of digital forensic analysis are the subject of doctorates in computer science, and are still very much a developing field. But by combining technical expertise with journalistic experience, InVid hopes to address all the issues around using video from third-party sources in news over its three-year funding period, building tools which newsrooms and journalists can use in the process.

“We’ll also be looking at the legal requirements,” said Jochen Spangenberg, innovation manager at German broadcaster Deutsche Welle, also in the consortium. “What can you do, what can’t you do, how should you deal with eyewitness media, what are the dangers, how do you protect sources and journalists.

“This is all taken into consideration, not just the technical solution but a solution that takes ethical issues into account but also legal issues.”

This broad assessment of the multiple factors in play will finish in the coming months, he said, combining experience already gleaned from similar projects like Reveal, where Spangenberg is also involved, before consortium partners start building prototypes that can be used in the newsroom. He hopes the first iteration will be available for testing this coming September.

The overall solution will be a paid-for product, said Mezaris, but a number of components will be made open source, available to anyone who may want to use them. After all, he said, the issue of fake videos is not just a concern for news organisations, but anyone who engages with digital media online.

“There are so many attempts to use video to deceive, there is an obvious need for the news agencies and media organisations but it is also to the benefit of the users, to everyone of us,” he said. “Of course in some cases it is not such a big deal to be deceived by a video of an eagle. But in many other cases it is more serious.”

Videos alleging war crimes or law breaking can – and do – lead to imprisonment, military action or political activism. Any efforts to see through the fog of misinformation on social media should be welcomed by advocates of the truth.