This article is part of a series on health misinformation.

The novel coronavirus has spread to over 60 countries alongside its darker cousin: false information about the disease, how it spreads and how we can protect ourselves against it.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has called it an “infodemic” as misleading or incorrect information is spreading faster than the virus. Whether it’s quack doctors pushing fake ‘cures’, conspiracy theories used to undermine opposition governments, hoax “symptoms” or funny memes, they create an environment that makes it hard to trust what we find online and add to the global panic and anxiety around the problem.

“Stigma, to be honest, is more dangerous than the virus itself,” said WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

When we come across content online that causes strong emotional reactions — like panic or fear — we can accidentally share things without stopping to think and check whether they’re accurate.

Agents of disinformation take advantage of this and create content designed to make us panic-share stories, angry-post reactions, forward happy puppy stories, and everything in between.

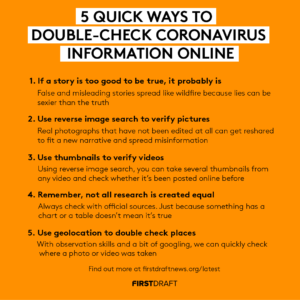

But we can fight the information disease together. Here are five quick things we can do to verify content online before we share.

Read more: Think ‘Sheep’ before you share to avoid getting tricked by online misinformation

Some stories are too good to be true

Story published by the Mail Online of unverified rumours that a creative Australian couple quarantined off the coast of Japan had two cases of wine delivered by drones

False and misleading stories spread like wildfire because people share them. Lies can be sexier than the truth.

A group of researchers from MIT found in 2018 that stories that trigger an emotional response are shared way more than straight news stories. Added to that, neuroscientists have confirmed that we are more likely to remember stories that make us angry, sad, or laugh.

In February, an Australian couple was quarantined on the cruise ship off the coast of Japan. They developed a following on Facebook for their regular updates, and one day claimed they ordered wine using a drone. Journalists started reporting on the story, people shared it on social. The couple later admitted that they posted it as a joke for their friends.

This might seem trivial, but mindless resharing of false claims can undermine trust overall. And for journalists and newsrooms, if readers can’t trust you on the small stuff, how do they know to trust you on the big stuff?

Tips:

- If a story is too good to be true, too funny, too infuriating, too sweet, too outrageous, it probably is. Go to the source before you post.

- Remember that journalists can fall for this too — so just because other news outlets are reporting a story doesn’t mean they verified it with the source.

- For more websites and tools to verify content online check out our verification toolkit and our Guide to Verifying Online Information.

Remember, not all research is created equal

Just because something has a chart or a table attached to it, doesn’t mean the numbers and the science behind it is solid.

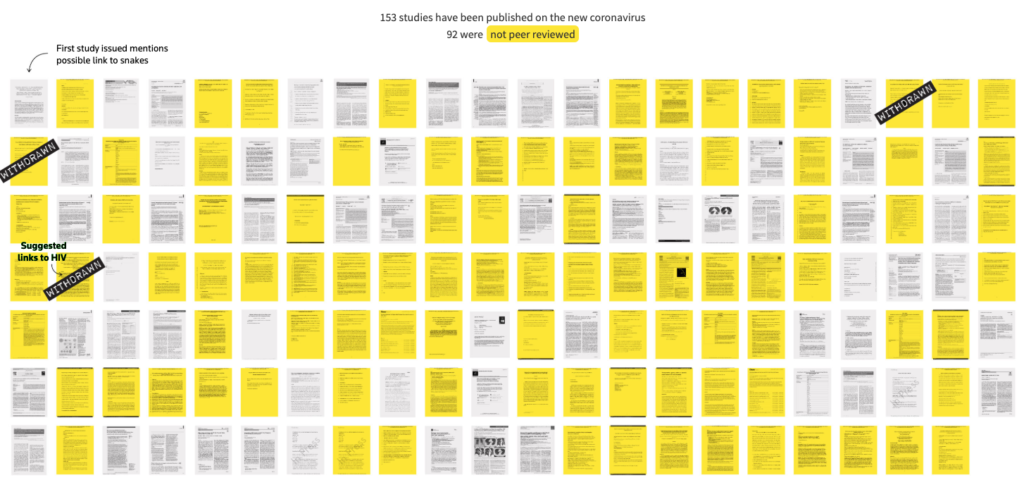

Reuters had a look at scientific studies published on the new coronavirus since the outbreak began. Of the 153 they identified, 92 were not peer-reviewed yet and some included some pretty outlandish and unverified claims, like linking coronavirus to HIV or snake-to-human transmission.

The problem with “speed science”, as Reuters called it, is that people can panic or make wrong policy decisions before the data has been properly researched.

So if you come across a chart, a table, a stat, or any number related to Covid-19, ask yourself:

Tips:

- What’s the source? Where did those numbers come from?

- Always consult official sources that aren’t part of any particular government.

- The WHO’s Coronavirus page has updated stats and recommendations.

- John Hopkins University keeps an updated map.

- For journalists, Journalist’s Resources does helpful roundups of verified research.

Verify images with reverse image search

A picture is worth a thousand words, and when it comes to disinformation it can also be worth a thousand lies. One of the most common types of misinformation is images appearing in a different context: real photographs or videos, that have not been edited at all, get reshared to fit a new narrative.

Some of the most shared photos of the Amazon fires of 2019 were outdated or unrelated and some of the latest maps showing the spread of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) are misleading.

But with a few clicks, you can verify images shared online and in messaging groups.

Just like you can “google” facts and claims, you can ask a search engine to look for similar photos and even maps on the internet to check if they’ve been used before for other stories. This is called a reverse image search and can be used to search Google, Bing, Russian website Yandex, Chinese site Baidu and a bunch of other databases.

For example, in 2014, Reuters published an image of an art project in Frankfurt, Germany, which saw people lie in the street in remembrance of the victims of a Nazi concentration camp.

In January, Facebook posts receiving thousands of shares featured the same photograph to falsely claim the people in the photo were coronavirus victims in China.

A photograph of an art project in 2014 in Germany that got shared on Facebook in 2020 to falsely claim the people in the photo were coronavirus victims in China.

A quick look at the architecture reveals it to look very European. Then if we take the image, reverse image search it and look for previous places it has been published we find the original from 2014.

The whole process takes a matter of seconds, but it’s important to remember to check any time you see something shocking or surprising.

Tools

- On desktop: We recommend RevEye’s Plugin to search for any image on the internet without leaving your browser.

- On your phone: If you’re out and about or a shady story was just shared on your family whatsapp you can use TinEye on mobile phones to do exactly the same thing.

Verify videos using thumbnails and InViD

It’s not just coronavirus that spreads, so do fake fart videos. This silent but deadly video claimed to show people caught farting by thermal cameras that were monitoring temperature for possible coronavirus patients.

But after reverse image searching screenshots of the video, you can find that the original is a joke video from 2016. The video was created by an online group called Banana Factory, who added the offending ‘clouds’ by computer, before it was shared by websites like LadBible and Reddit.

Video showing people caught farting by thermal cameras was originally made in 2016 by a company called Banana Factory.

What is the problem with sharing funny fart videos you ask? Our trust in the media and the information we find online is crucial to democracy. If people think anything they find online could be fake, it gets harder and harder to believe in anything. Even if the subject is just farts.

Around the world, fact checkers have been verifying videos which falsely claim to show the symptoms or impact of coronavirus, all of which or just old videos reshared with a new caption. As WHO chief Dr Tedros said, this kind of scare mongering can have a more dangerous impact on the world than the disease itself, causing panic and draining resources which could be better used to deal with real-world problems.

Before you share that clip with your various chat groups, triple check you’re not getting fooled.

Using reverse image search, you can take several thumbnails from any video and check whether it’s been posted on the Internet before.

Tools

- The folks at Amnesty International developed a tool that lets you automatically get thumbnails from YouTube videos as well as give other useful information.

- InVid’s video verification plugin has some very effective tools to verify images and videos plus their “Classroom” section is filled with other tutorials and goodies.

We can take the wind out of disinformation together. And if you’re hunting for quality fart-related video content check out this wonderful machine from Mythbusters’ Adam Savage. It’s a gas.

Use geolocation to figure out where a photo or video was taken

One of the best tools to spot disinformation is on our face: our eyes. With observation skills and a bit of googling, we can quickly decide whether a photo is from when and where it claims to be.

Take the tweet below from The New York Post. It’s about the first case of confirmed coronavirus diagnosis in Manhattan. Alessandra Biaggi, the American Senator that represents the area, quickly pointed out the photograph they used is of an Asian man in Queens.

But how can we double check who is right?

…so then why are you using a photo of an Asian man in Flushing, Queens? https://t.co/729wbYmb8G

— Alessandra Biaggi (@SenatorBiaggi) March 2, 2020

We can use the street signs and store signs in the photo to find the same spot on a map. Search for “Duane Reade Main Street New York Queens” and we will be presented with three options.

In Google Maps, we can drop the little yellow man onto the roads to get streetview and see the same buildings from the same perspective as the photographer.

Tips

- Look for clues in the architecture, language of signs, what people are wearing, what side of the road are cars driving, names of businesses, etc.

- What can you search for and verify? Can you find that same spot on a map?

- You can flex your observational skills with our interactive observation challenge. If you’re a pro try our advanced geolocation challenge.

Think before you share

Just as we all have a role to play in stopping the spread of the real virus, we also have a responsibility to not share false information with our friends and family, creating unnecessary worry or panic.

Think before you share and remember these tips to check things out. Sometimes the laughs aren’t worth the problems they can create.

Check out more guides and tips from First Draft on how to verify online information and responsibly report on false claims.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by subscribing to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.