Facebook’s Ad Library might not seem like an obvious place to look for stories about misinformation and influence during the pandemic. The social media giant banned misleading coronavirus ads early in the crisis but its archive for promoted posts has been a consistent source for journalists since its launch in 2018.

Donald Trump’s re-election campaign spent more than $32 million on Facebook ads between January 2019 and June 2020, according to The Washington Post. And despite the restrictions, BuzzFeed News found Facebook was still accepting money for fraudulent ads selling face masks to unsuspecting users in May, although the platform later banned the advertiser.

Using the Facebook Ad Library to uncover these types of stories was the basis of a webinar led by First Draft investigative researcher Madelyn Webb, an extensive user of the library, and training and support manager Laura Garcia.

The basics

The library contains data on all ads run on Facebook, Instagram, Messenger and the Audience Network, which extends advertising campaigns from Facebook to separate platforms using the same targeting data.

You can access the library through a Facebook Page of interest by selecting “Page Transparency” on the right hand side, clicking “See More”, navigating down to “Ads From This Page” and clicking “Go to Ad Library.”

You can also search for ads on specific subjects, either by searching for Pages which use specific keywords in their name or changing the search type to “Issue, Electoral or Political” and looking for individual ads directly.

For example, when the coronavirus pandemic was emerging, a search for “coronavirus” in the library uncovered reams of ads from both reputable organizations and more dubious sources, Webb said. She recommended using one specific keyword for the most relevant results.

In the US, Facebook has added a specific section for housing after journalists found the platform allowed advertisers to restrict housing-related ads based on the viewer’s race, color, national origin, and religion.

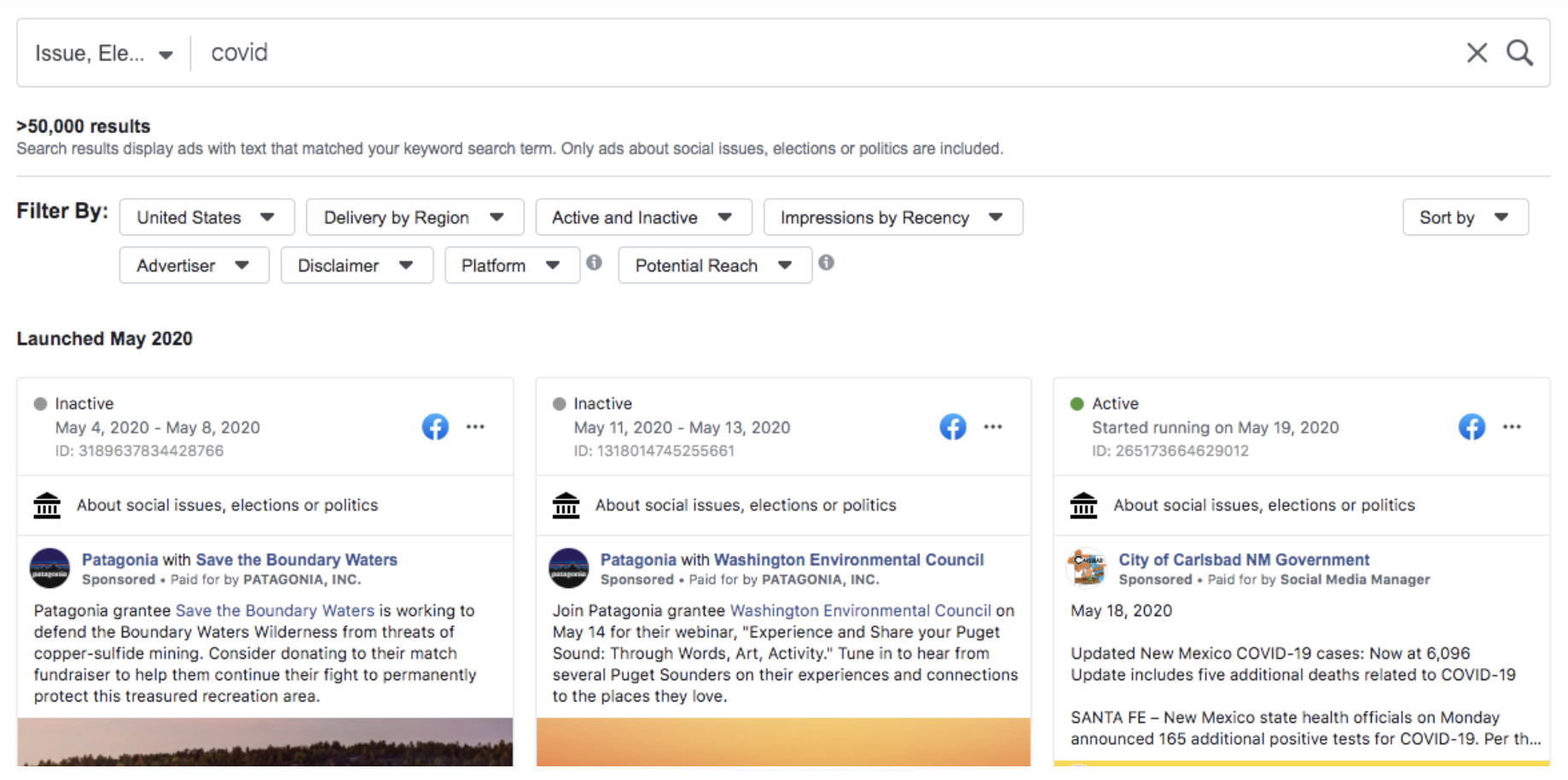

Users can also filter ads based on a number of different details, including geographic region, whether ads are active or inactive, or by how many unique users might have seen an ad (described as “Potential Reach”).

The name of the person who paid for a political ad is displayed in a disclaimer at the bottom of each promoted post. One thing to look out for is when the name of the Page and the one on the disclaimer don’t match, Webb said. An example of this might be a local political candidate who might be running ads on several pages.

Users can also search for ads using certain keywords by going to a Page of interest, clicking “Issue, Electoral or Political” and entering words of interest in the search box which appears near the filters.

This function, however, doesn’t always return results, Webb said. “I suspect they’ve changed when it pops up so be warned this might be out of date in another year … Facebook changes it a lot.”

Behind the data

To find more information on who might be behind a particular ad, click “See Ad Details” from the search page.

“Information from the advertiser” reveals the business address, website, phone number and other details.

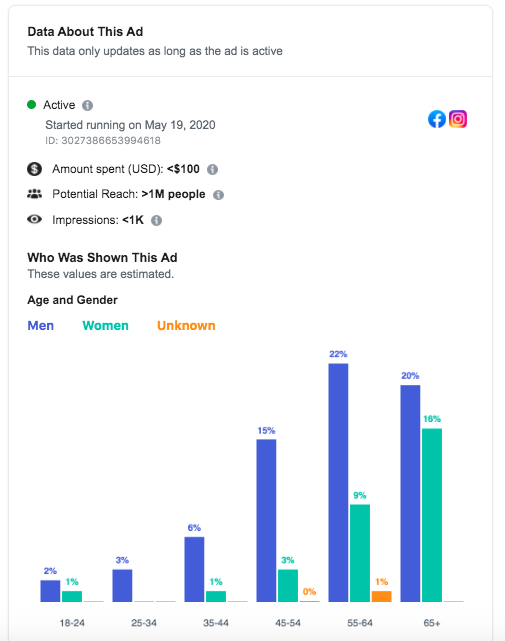

Further down the page lies demographic data on who the advertiser is trying to reach based on age, gender, and location.

You can also see the amount spent, an ad’s potential reach (how many people are in the targeted audience for a certain ad) and impressions (the total number of times the ad was shown) in numerical ranges. Bear in mind that these numbers are estimates, Webb said.

The “About the Page” section contains additional details on total spending and other ads from the Page — useful for getting a broader look at a whole campaign or other activity.

Advanced searching

Facebook releases a daily report on political ads detailing what it describes as top searches, spending totals and ad numbers covering the past two years, and a spending tracker, which reveals the highest daily spenders or when there are spikes in spending on ads.

Only ads that have been labelled political, electoral or related to specific issues are included in the report. “It’s very hard to figure out how exactly Facebook goes about delineating that,” explained Webb, who said she assumed it is based on keywords or information from the advertiser.

Pages spending the most or posting the highest volume of ads could be the source for a story, particularly during or ahead of an election.

The report also allows users to search for specific advertisers and find a breakdown of spending by advertiser or region.

For journalists hoping to go deeper into the Facebook Ad data, you can download the daily report as a CSV file by hitting “Download Report” at the bottom of the page.

For more comprehensive data analysis, you can use the Facebook Ad Library API.

The archive can be limited

There are challenges to using the Ad Library, however.

Advertisers often specify email addresses that do not contain identifiable features or reveal little about their origin, such as that of a shared workspace. Digging deeper on any other information contained in a disclaimer can prove vital to finding the true source, Webb said.

The platform also doesn’t provide always details or consistency on why some ads are removed, Webb discovered during her research.

In one case, three identical ads were promoted by three different Pages, each with the same disclaimer. Facebook removed two for breaking advertising policies but the third remained active.

Three identical ads run on three different pages with the same disclaimer, but only two of them were taken down. Why not the third? Would be great if the Ad Library would provide specific reasoning for removal. pic.twitter.com/3VJGb5ReQy

— Madelyn Webb (@mdywebb) May 26, 2020

Researchers and journalists have also found the Ad Library, Ad Library Report and the Ad Library API to be unreliable. In one example, some 74,000 political advertisements disappeared from the archive two days before the UK’s 2019 election. There have also been issues with delays in delivering data, design limitations which prevent users from retrieving a sufficient amount of data, and other bugs which can affect access to the library.

While there are caveats to what information is available through the Facebook Ad Library and related transparency tools, Webb said, they can prove to be an invaluable starting point for many investigations.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.