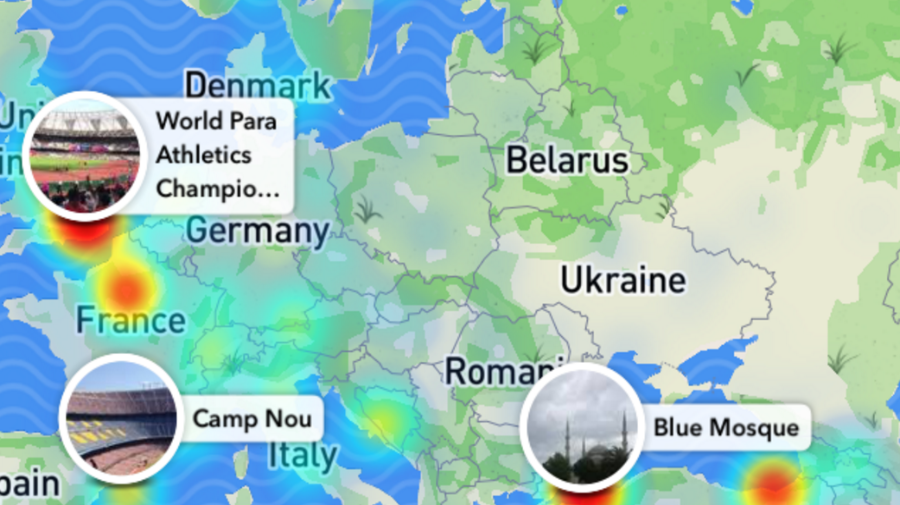

When crowds of G20 protesters clashed with riot police in the streets of Hamburg, Germany, witnesses took to Snapchat to document the chaos. Journalists around the world watched in real time as snaps of flame-engulfed cars and water-pummeled protesters sprang up on the app’s map.

Snapchat’s unique combo of closed messaging and anonymous public contributions has historically made it difficult for journalists sourcing from social media to utilize. However, last month’s release of the Snap Map, and its activity during the G20 protests, has renewed interest in the platform as a reporting tool.

Pinch the Snapchat home screen to reveal the Map.

Until recently, Snapchat had only a few uses for journalists. If you already had a source who had shared their Snapchat code or username, you could screengrab their snaps for content. Otherwise, you could also use it to engage sources and skirt the deluge of requests from other journalists on Facebook and Twitter. But that’s been about it.

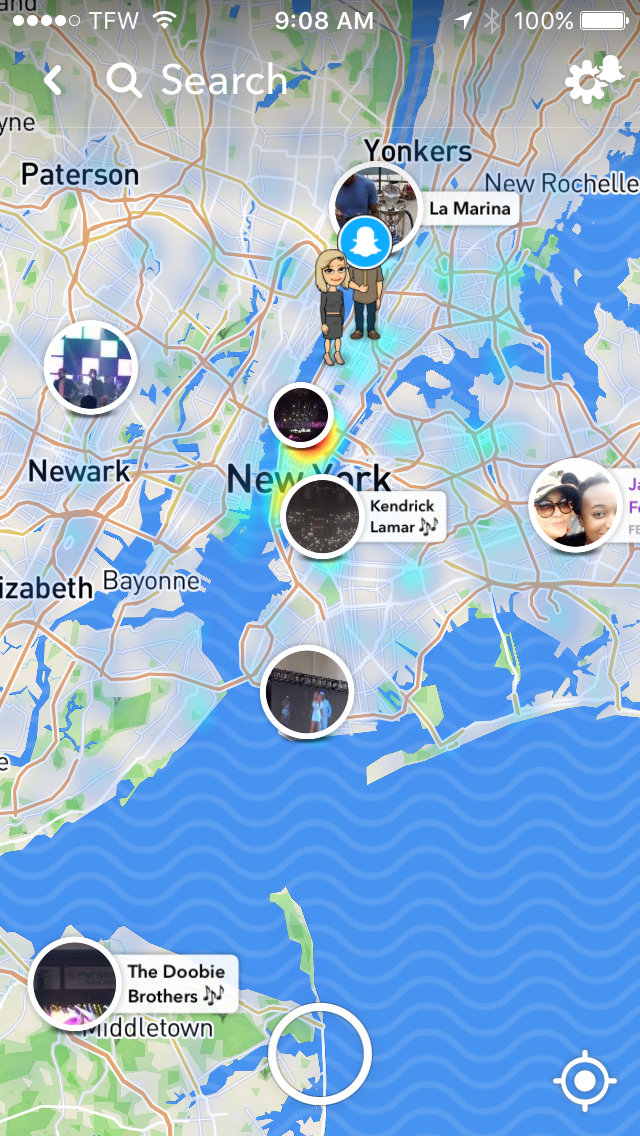

A recent Map of a “New York City” search.

Snap Stories, while often compelling and newsworthy, don’t provide the usernames of their contributors, so there’s no way for journalists to reach out to witnesses for comment or permission to use their content. Additionally, geo-fencing has long meant that only local stories could be seen.

So, how does the Snap Map change things?

By pinching the home screen, Snapchat users can now pull up a detailed heatmap of all public stories, everywhere. The map also plots friends who have chosen to share their location.

These features give a few things to journalists: Those with a general idea of where an event is can now poke around the Snap Map to find a more exact location. If the event you’re tracking is moving, like a protest, you can also get a sense of its path.

“I found it really useful, on the second morning of the [G20] protests, to look back at where the protests had been the night before,” said Hazel Baker, global head of user-generated content newsgathering at Reuters. “I could see the remnants on the Snap Map. They had gone a bit cooler—they’d gone blue. Meanwhile, the red blobs had moved up to different points on the map.”

Information from the Map can then be fed into other platforms like Twitter as a search for coordinates or a street name. Alternatively, these details could be used to direct journalists on the ground. (But, of course, Periscope and Facebook Live can also help journalists locate activity.)

The snaps displayed in Map stories are still unattributed, and Snapchat is unlikely to change that. Already, the new feature has triggered privacy worries, particularly among parents, though these appear to focused on the location-sharing aspect.

Moreover, privacy worries are counterbalanced by concerns that the Map’s combination of anonymity and wide-open access is likely to incite copyright issues.

“What we’re going to see inevitably now is that Snapchats will be used without the content owner’s permission, simply because the news industry has no way of contacting owners,” said Joe Galvin, news director at Storyful. “I don’t think that’s an ideal situation.”

Yet it’s unclear that revealing the identities of story contributors would ultimately result in more usable content for journalists.

“I think sometimes the anonymity afforded to Snapchat users is actually what’s encouraging so many people to participate in this mass—essentially a mass citizen journalism project,” said Baker. “Because they’re not worried about getting bombarded by the media.”

All things considered, the Map seems unlikely to move Snapchat to the top of social newsgathering pipeline. In situations where you don’t have a clear idea of where a breaking-news event might be happening, Snapchat could be a valuable initial geolocation tool.