The Online News Association recently launched the Social Newsgathering Ethics code. That code*, created over the period of more than three years, brings publishers, broadcasters and journalistic institutions together under a common set of standards for operating in this arena.

Central to the code is the idea that ethics in social newsgathering is not anti-competitive — we can still fight for exclusives and we can still beat our colleagues to those with the best content. An ethical approach simply means operating in a way that will allow us to keep doing so in the future.

Below are five themes from the code that directly relate to sustainability in newsgathering.

Being transparent with the audience about the verification status of UGC

This is very simply about trust.

The audience has exactly the same access to newsworthy pictures and videos on social media that journalists have. They can follow a story like we do, they can carry out the same checks we can — they expect it of us and they will increasingly know how and why mistakes are made.

We now have a plethora of verification resources and processes we can follow. If we are less than clear about the state of verification — when we are either unsure or hedging our bets — the audience will lose their trust. But it doesn’t just have to be ‘verified’ or ‘unverified’. You can instead talk about what you are able to authenticate or not— and why — and give the power back to the audience so they can make their own informed opinions.

Consider the the emotional state and safety of contributors

The majority of journalists’ social newsgathering efforts are conducted in a very public forum. Our audience can see our efforts and they are increasingly vocal about bad or insensitive practice.

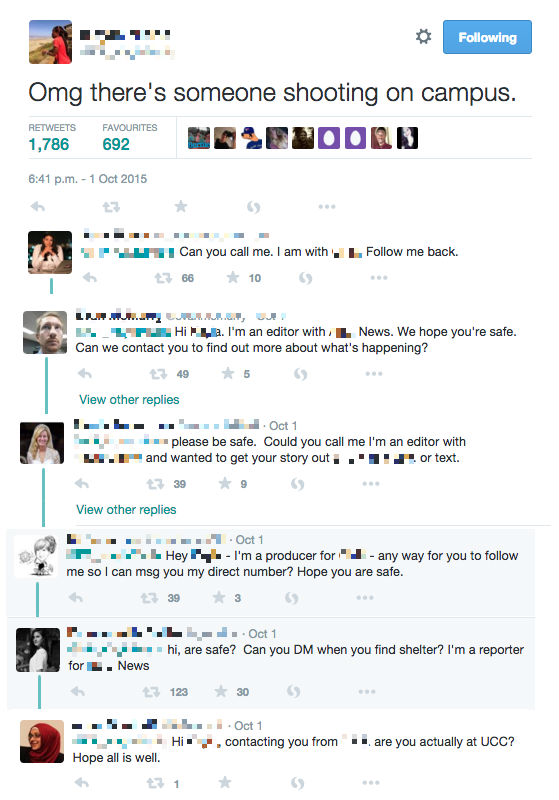

Scores of reporters contacted one eyewitness to the Umpqua Community College shooting in October 2015 while the situation was still active

The response from the public who saw these approaches were not positive

As an industry we have spent huge amounts of time, money, resources and training on creating the best social publishing and engagement strategies. Yet all of that work can be undone if reporters or producers are seen to be harassing people in life-threatening situations. Or any situation for that matter.

We all understand the need to get the first-hand account or footage from the scene. But at what cost? Consider these points:

- If you DM someone in a live situation where their life is at risk, will they really be in a position to do a phone interview with you?

- Wouldn’t it be better to wait to ask them until you know they are safe?

- If one person in your organisation makes the request for a photo but gets no response, what does it look like to the outside world — and the person you are asking — if they receive the request from two or more of your colleagues as well? This happens far more regularly than you might expect.

- By communicating with someone in a dangerous situation on Twitter you could amplify their Tweet in a way they never expected and risk exposing them to someone who might cause them harm.

- If someone is hiding and you start messaging them, what happens if they left their phone on and the notification gives away their location?

One might argue that it isn’t our problem, the person shouldn’t be sharing their situation on social media in the first place if they don’t want to be found… But this argument doesn’t matter. If people stop sharing images and information because of journalists’ actions we’ll have very little content to work with in the future.

Also, harassing people rarely works.

The eyewitness to the UCC shooting did not respond to any requests for contact from journalists

Seeking informed consent for the use of UGC through direct communication with the individual who created it

You might have a fair dealing or news access loophole in the law of your country which allows you to take the imagery from an individual’s social account and use publish or broadcast it in your coverage. Yet, in the long-term, it is more sustainable to ask and receive the actual permission you need before taking the material.

- You’ll likely be able to arrange archive rights: if you take it without permission under a specific loophole like this then you probably don’t have the right to use it again and again. You certainly can’t use it for that “year in review” you had planned for December.

- You’ll know that they are unlikely to retract their permission, which they can do on Twitter. What does this have to do with sustainability? Well, if you only seek permission via a Tweet you will technically have to monitor their Tweets forever more in case they choose to retract that permission. If they do (at any point, ever) then you’ll have to remove that content from anywhere it is still visible. That could be quite time consuming.

Eyewitnesses have every right to withdraw the permission they give on social media at a later date, and if the initial wording is not clear then the likelihood of withdrawing permission is more likely — Adam Rendle

- People increasingly have the opportunities and the intention to monetise their content. By taking their imagery without permission you could be denying them of that income and turning them off to potentially working with you in the future.

- Your audience might wonder why it is ok for you to take their content without permission but apparently it isn’t ok if they take yours. Frankly, it doesn’t matter what the law of the land might be. If your audience think you are being unfair and treating them badly they will at best leave you, and at worst take some kind of action.

Consider the risk inherent in asking a contributor to produce and deliver UGC

Consider the possibility that using content that has already been created might often be easier to verify and use with confidence than content you ask to be created. If you ask someone to capture something for you then it might influence the nature of that content. And if they get injured — or worse — doing something that you asked them to do, then who is responsible?

This is not to say that there is no place for assignments of any kind.

We all need beautiful snow pictures but we don’t necessarily want to ask someone to go out in a hurricane for us. Likewise, in an unknown, active situation we need to take different precautions when asking for people to take action.

Some requests for footage pose little risk to an eyewitness, others could put them in considerable danger

Our industry never wants to be in the position where someone acts on our instructions with severe consequences.

Being transparent about how content will be used and distributed to other platforms

Journalists know how news content is spread and distributed. They also know what is likely to have a huge impact when published. It is fair to say that eyewitnesses often share newsworthy content on social platforms because they want their friends to see it. They aren’t thinking about us.

This is becoming more of an issue as news organisations increase their newsgathering reach, accessing content in regions that they would have traditionally relied on agencies to cover for them. It is not reasonable to expect people to have heard of your news brand in every corner of the world and therefore have a full understanding of how their content might be used by you and received by your audiences.

It might be worth considering informing the content owner if:

- Their content is potentially inflammatory and using their name might attract unsavoury attention

- Their content is going to be shared on social media with their handle or username

- Their content is going to be embedded on a site that is likely to receive a lot of traffic and expose them to regions, populations and individuals they never expected or intended it to reach

- You plan on using the content on a platform that isn’t typically associated with your brand, especially if you are not known to them. For example, you are a TV brand using it on a social network or you syndicate your content to third parties.

“The Media” hates being lumped together when criticism comes our way. But, when it comes to social newsgathering bad practice, this is exactly what is happening.

By considering the future impact of our current ways of working we should be able to start creating a sustainable relationship with those members of our audiences who have content the world needs to see.

*Fergus Bell is co-founder of the ONA social newsgathering working group who led the creation of the Social Newsgathering Ethics Code.