As 28 countries prepared to head to the polls to vote for a new European parliament in late May, many analysts and commentators feared a repeat of the information chaos of other recent elections, from the U.S. to France.

Whether it was Macedonian teenagers making thousands in ad dollars from spurious stories, Kremlin-backed trolls sowing division among voters, or homegrown activists throwing truth and caution to the wind, fact-checkers, journalists, governments and others were on the lookout for signs of interference or disruption.

Instead what emerged was a much more complex picture. First Draft worked with media partners from more than a dozen European countries in the weeks surrounding the vote, collaboratively investigating and debunking disputed claims from across a continent of social media users as part of the CrossCheck project.

Many other experts and researchers were involved in other collaborative projects or research initiatives, so we spoke with several of them to reflect on what we learned about information disorder during the 2019 European elections.

Looking for the Bogeyman

While it is too early to dismiss the possibility of foreign interference altogether, fact-checkers and officials said they had not found evidence of a significant campaign to disrupt the election.

In our analysis of the European Parliamentary Elections we identified a number of potentially automated accounts amplifying the @brexitparty_uk whilst attacking @ForChange_Now and @Conservatives. Read at: https://t.co/8HgDomGCG3

— Jacob Davey (@jacob_p_davey) May 21, 2019

In fact, the amount of outright lies spun from nefarious actors to influence the voting public was far lower than expected, said French journalist Jules Darmanin, who led FactCheckEU, a collaborative project around the EU Elections from the International Fact-Checking Network.

“There was an uptick in misinformation around the European Union but I didn’t feel like there was this swarm that we experienced in past elections like the US elections or Brexit referendum or even the French presidential election during which misinformation was coming at pace,” he said.

The huge scope and complexity of elections in at least 24 languages across 28 countries may have been a factor. “If you are a bad actor who wants to have an influence in the elections it would take a lot of resources and a lot of skills for results [in the election] which wouldn’t be as important as the result of a referendum or a presidential election,” Darmanin said.

Hey everyone! @JulesDrmnn here with some thoughts about disinformation after this election week. The thing is, we didn’t see the massive surge in hoaxes and bullsh*t fact-checkers are used to see when an election is coming up.

— FactCheckEU (@FactcheckEU) May 27, 2019

Darmanin warns that looking for one sole source of information campaigns “can lead you to ignore some other things.”

“This is still being thought about by a range of different actors in an un-nuanced fashion and people still want to look for the big Russian bogeyman in the room,” agreed Jacob Davey, a research manager at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a London-based think tank specialising in solutions to extremism and polarisation.

“I think you’re not finding a big conspiracy anymore but instead this normalisation of a tactical playbook for campaigns which ultimately pushback against the fundamentals of democracy.”

Democratising disinformation

Oxford University’s Internet Institute tracked deliberately misleading “junk news” around the European parliamentary elections during two weeks in April. Researcher and doctoral candidate Nahema Marchal found the levels of junk news fell far short of what they might have expected. “Instead what tended to dominate were these domestic, hyperpartisan and hybrid sites,” she said.

The #EUelections2019 are around the corner. Worried about #misinformation? Our latest study finds that junk news is not as prevalent as feared.

Summary of our findings + link to data supplement below ? https://t.co/4kvd0FL7AP

— Nahema Marchal (@nahema_marchal) May 21, 2019

The latest report from Demos, Warring Songs: Information Operations in the Digital Age, reached a similar conclusion. “The digital world has done to warfare [what it did to other spheres of life],” said Carl Miller, co-founder of the Centre for Analysis of Social Media at think-tank Demos, who studies the changing parameters of war and power. “The digital world has collapsed barriers to entry and everyone’s getting involved now.”

“You can make a very warped picture of the world simply through the selective, judicious cherry-picking of truths” – Carl Miller, Centre for Analysis of Social Media

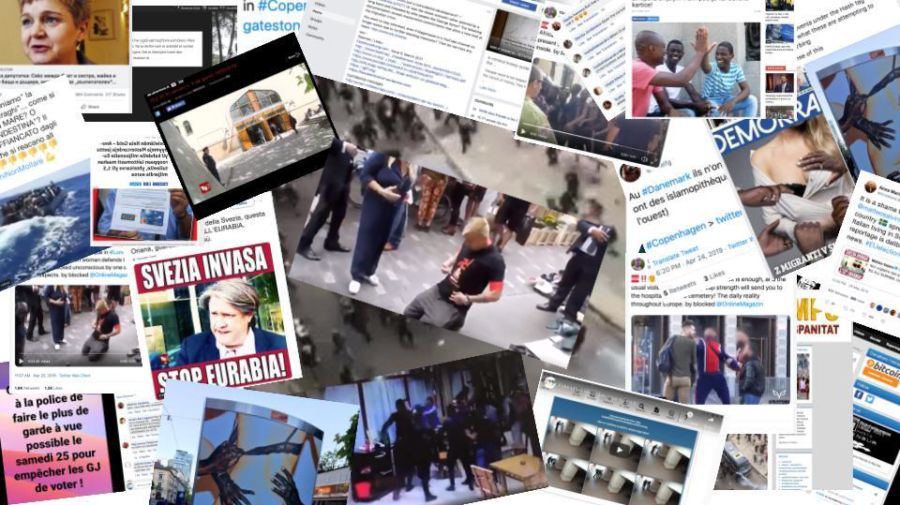

The tactics of disinformation used for foreign influence appear to have been picked up by anyone with an agenda to push or an axe to grind, often mixing the truth with highly misleading headlines or footage plucked from their original context to present a very different story.

“You can make a very warped picture of the world simply through the selective, judicious cherry-picking of truths,” said Miller.

Davey describes the proliferation of such tactics as the spreading of the “Putin playbook”. But where information campaigns in 2016 may have spread outright lies to push an agenda, the resulting efforts to counteract so-called “fake news” have seen a shift from information warfare, to narrative competition around “wedge issues” which divide societies.

Migration and Islam dominate

The Oxford Internet Institute also found that when junk news sites “do report on real stories they will cherry pick or be extremely selective in their reporting to convey a very one-sided narrative about an issue such as migration or crime,” Marchal said.

These websites focussed on Islam and migration, linking them to crime and terrrorism. For example, after the fire in Notre Dame Cathedral, the institute found “a lot of stories hinting that the fire itself had been plotted by some Muslim terrorists.”

Darmanin told a similar story, especially in finding pictures and videos crossing borders to be repurposed completely out of context. This was also the subject of many investigations in CrossCheck Europe. Both projects repeatedly found misleading information in the form of old footage resurfaced and repurposed to create the impression of daily crimewave committed by non-Europeans recently arrived on the continent.

This is our recently published report looking at information operations targeting Germany, Italy and France. We’re dealing with something v. different from fake or junk news – far more the selective cherrypicking of facts from reputable sources. https://t.co/5dVmMqsnHJ

— Carl Miller (@carljackmiller) May 31, 2019

Footage of a riot in Algeria was repurposed and attributed to migrant violence in France and Denmark. When a French bar owner stabbed an employee in Spain, the video was shared as a refugee crime in German, English and Polish tweets. A bar fight between locals in Romania was reported on social media as “Polish hooligans” protecting women from “Turkish Muslims”.

Migration and free movement has long been a lightning rod for animated political conversations across Europe. The modern age of democratised publishing has allowed opponents of migration to misrepresent reality in multiple languages. Now, the most common theme of misinformation that migrates between countries is migration itself.

“I think that’s the main reason it works so well,” Darmanin said, “it’s harder to check, it’s inciting a very strong emotional response and it’s part of the national conversation in Europe.”

An investigation into a video that was suspected to be misleading on the CrossCheck Europe platform

Climate chaos and online trolls

The European elections also saw an increase in a different type of misinformation, following the high profile protests led by 16-year old climate activist Greta Thunberg across the continent and the increasing voter share of Green parties.

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue detected “co-ordinated harassment [of Greta Thunberg] from the AfD in Germany, explicitly engaging in online harassment because she has Asperger’s Syndrome and because she’s a young woman,” said Davey.

This was an extension of the misogyny linked to online trolling culture, he said. What’s more, Davey said this kind of trolling culture has been normalised in online discourse, to the point where it has broken into the mainstream.

The UK Independence Party recruited as candidates several members of this culture: anti-feminist Carl Benjamin and self-described “professional shitposter” Mark Meechan, who have a combined following of almost 1.5 million subscribers on YouTube.

In Italy, Matteo Salvini picked out some critical female journalists, Davey said, who then became the subjects of a torrent of online abuse. “I think that’s one of the worrying things about these techniques,” he said, “they are effective at silencing journalists, at silencing researchers.”

A partial picture

The tech platforms also play a role in what researchers and fact-checkers are able to detect.

By virtue of a relatively open API, most research on online information flows is conducted either through Twitter or by analysing websites. Despite having more than 2 billion users Facebook is one of the harder platforms to probe and private messaging apps largely remain a locked box, at least in terms of broad analysis.

And drawing conclusions from a small dataset risks partial and possibly misleading findings, like trying to draw a picture of a huge ballroom by looking through the keyhole.

“We go where the data is available, and where it is, and where we can examine it and analyse information” – Nahema Marchal, Oxford Internet Institute

“Unless we have real meaningful partnerships between researchers and platforms, as these efforts are being researched and refined, what we’re going to be able to provide will always be ad hoc,” said Marchal, of the Oxford Internet Institute. “We go where the data is available, and where it is, and where we can examine it and analyse information.”

“But in order to get a full picture of what is going on we need to have more direct access to data,” she said. “The efforts they’re making are not sufficient if we cannot see what is going on in the background.”

For updates about First Draft’s work and team developments, become a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect that the number of official languages of the European parliament is 24, not 27.