This article is available also in Deutsch, Español, Français and العربية

When the election was called on April 18, we weren’t planning on taking part. It seemed pretty hard to organise something useful by June 8 and, having deployed the CrossCheck team to monitor the French election, our evaluation at the time was that misinformation was even less likely to spread in the UK than it had across the channel.

But by May 1, we’d changed our minds. Reflecting on the 67 stories we debunked during the CrossCheck project convinced us of two things:

- Disinformation comes in many forms. There wasn’t going to be a ‘Pope endorses Trump’ type fabricated article, but there would be plenty of exaggerations and misleading content on hyper-partisan sites, as well as memes, manipulated photos and videos.

- To fight mis- and disinformation, you need expert factcheckers working alongside social discovery and verification specialists. We hadn’t gone deep into the technicalities of factchecking during CrossCheck and we learned from France that it was something that we needed to do.

To date, factchecking and verification have been seen as distinct journalistic skills. Undertaking a forensic analysis of a manipulated video purporting to show migrants attacking a woman is considered a different journalistic skill to factchecking a politician’s claims about the number of migrants who have entered the country. But from the audience’s point of view, they simply want to know what is true and what is not.

According to Full Fact, the UK’s leading non-partisan factchecking organisation with 7 years experience of factchecking political claims, “Social media is how many people get their news, so factcheckers need to be on top of what is being discussed there. And social media verification can be held to a higher standard by the use of factchecking: rather than just linking to the article where a meme got its numbers from, factcheckers can find the primary source and determine the accuracy of what is being shared.”

So First Draft and Full Fact joined forces, with the hope of combining the skills of verification and factchecking. Previously organisations like ours have been moving in different circles, going to different conferences, competing for funding. Working apart like this no longer made sense.

We worked together to monitor online conversations related to the election and provided newsrooms with a twice-daily newsletter of information we believe might trend. We monitored the main themes being discussed online as well as identified inaccurate content, rumours and claims being shared. We sent out 33 newsletters over three and a half weeks, and they are a treasure trove of information as we start the post-mortem on this election result.

The project demonstrated that:

- Factcheckers and verification specialists need to work together much more closely.

- Factcheckers should be monitoring online conversations in real-time as well as official sources.

- Deciding what to debunk isn’t easy. There were many articles, memes and photos that we didn’t touch, knowing that to do so would have provided unnecessary oxygen to something which only had a very small audience. But making these decisions was a challenge every day.

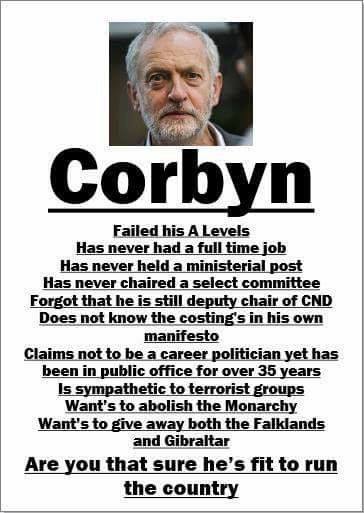

- We need to stop worrying about fabricated news sites (otherwise known as ‘fake news’), and start thinking more about memes — vivid images with text overlaid. As we work in different electoral contexts, we’re seeing that memes are how misinformation is being effectively spread.

- We need to start taking hyper-partisan sites seriously. This type of site is one place where campaigns are being fought.

Over the past four weeks, First Draft’s social newsgathering and verification specialists have been monitoring the social web, using sophisticated scraping techniques, as well as using some of the smartest technology platforms (including NewsWhip, Trendolizer, Crowdtangle, Trendsmap and Signal) to identify rumours, statistics and graphics that needed factchecking. As Full Fact admit, they wouldn’t previously have known that these rumours were taking hold as they just weren’t looking.

Online conversation around the election was about specific issues like the NHS or taxes, and was punctuated by the use of heavily shared graphics supplying misinformation along certain themes.

While the team could investigate the digital footprint of someone who first posted a political graphic or meme, we quickly realised how frequently these images drew on the ‘supposed credibility and authenticity’ of statistics and voting records, combining them with compelling visuals and easy-to-relate examples.

Image shared by “The Bare Naked Ugly Truth” Facebook page.

The NHS formed the basis of the most widely shared content of the entire election. A video on the Facebook Page ‘NHS Roadshow’ gathered 10 million views over the course of campaigning, and was the subject of an extensive factcheck by Full Fact,which analysed the claims one by one. It concluded that many of the claims in the video were largely correct, but that some just could not be factchecked.

Apart from health, one meme claimed recent Conservative governments had increased the national debt by more than “any Labour prime minister combined.”

From the “Britain Is The People” Facebook page.

This isn’t a fair comparison because both the economy and the government have grown, which is a fact of little concern to those sharing.

Politicians were targeted with misquotations, and their political actions in public office were often taken out of context. An image attributing a homophobic quote to Theresa May spread rapidly, despite no evidence of the quote’s truthfulness and the creator of the meme appearing to admit it had been fabricated. Widely circulated images made inaccurate claims about the expense records of David Davis; Damien Green’s attitude to worker’s rights and the Prime Minister’s voting record as an MP, which received 1500 shares on Facebook.

From the “Anti-EU pro British” Facebook page.

Statistics add an extra layer of apparent validation to a claim, making it more shareable online. When the issue of police cuts came to public attention in the wake of attacks in London and Manchester, graphics spread simplifications of a complex issue and memes reduced the claims further. Full Fact released its own findings on the subject during the campaign, but these older images still circulate. Other popular graphics, such as this image shared more than 40,000 times on Facebook, which features a bar chart with misleading proportions, show just how pervasive misleading statistics can be.

Sometimes these images are aesthetically striking, pay attention to the visual grammar of the internet, and often require a lot of work to create. Images like these sometimes look professionally produced and are shared despite the fact they’re conduits of misinformation, like the infographic on Labour’s ‘magic money tree’, retweeted by more than 4,000 accounts.

Our friends at Full Fact summed up the project in this way:

“This election was different for a few reasons. We saw terrorist attacks that brought a halt to public campaigning, but the Internet continued. There was also a noticeable lack of facts in the political campaigning. A lot of policy promises focused on the future without saying much about what these promises would need now, so much so that we wrote a piece on what the parties weren’t saying.

The most important thing we learned from First Draft was the importance of comprehensively monitoring non-traditional news sources. First Draft’s use of tools such as Trendolizer and NewsWhip enabled us to see what people were really asking. Some of our most popular work was on a video about the NHS and an infographic on the UK economy that had gone viral. When we produced this content, it was shared by far more people than our traditional factchecks because we were talking to people about things they were already interested in.

Working with journalists who were producing newsletters twice a day meant we had to produce more reactive content that was more varied and often unrelated to the mainstream news of the day.”

Our collaboration was incredibly useful during this snap General Election, and we hope that this is just the start. The precision of factchecking combined with the ability to quickly recognise claims that are spreading, can help us provide verified and factual information to the public.

Facebook and Google News Lab supported First Draft and Full Fact to work with major newsrooms to address rumours and misinformation spreading online during the UK general election.

This is the first of a series of blog posts about the Full Fact-First Draft UK Election project.