If you live outside the United States, you might not be familiar with the country’s Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. It’s highly likely, though, that Covid-19 vaccine mis- and disinformation with roots in the sprawling database has spread to your country.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS, is a publicly accessible, crowdsourced database that acts as an “early warning” tool in the United States’ vaccine safety monitoring mechanism. It stores reports filed by individuals, healthcare providers and vaccine manufacturers detailing adverse events that occur after vaccinations of adults and children, regardless of whether a vaccine was thought to be the cause. Since its launch in 1990, the national database — co-managed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) — has proven successful in alerting health authorities to possible adverse side effects from vaccines licensed in the country.

However, VAERS has its own adverse side effect: The unvetted and open nature of the system means it is prone to exploitation by vaccine skeptics, with the reports on the database misleadingly cited to stoke fears around Covid-19 vaccines. The fact that the publicly available VAERS reports are unverified and do not indicate the causality of adverse events is often conveniently ignored.

Common types of mis- and disinformation citing VAERS reports

Mis- and disinformation about Covid-19 vaccines based on the VAERS database has traveled internationally. First Draft researchers have recorded false narratives citing VAERS reports on just about every platform, including mainstream social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, fringe messaging apps such as Telegram and video platforms including YouTube and BitChute. Problematic claims about Covid-19 vaccines leaning on VAERS’ credibility have also been published in online articles and broadcast on television.

These narratives and claims have been shared in multiple languages, such as English and Spanish, and in countries from the US to France to Australia, highlighting their virality and global impact. An example of reach: One video posted on Telegram in January of a person using the VAERS website to describe Covid-19 “vaccine deaths” had been viewed some 220,000 times as of July 14.

Misleading TikTok post in English citing VAERS reports

Spanish-language Telegram post with misinformation about VAERS

Broadly, VAERS reports and data are often used in mis- and disinformation narratives to falsely assert or suggest that deaths, injuries or illnesses were caused by Covid-19 vaccines. However, as explained by the CDC and FDA, reports of adverse events following immunization with US-licensed vaccines can be made by anyone and may include incomplete, inaccurate, unverified or coincidental information. A CDC spokesperson told First Draft in a July 22 email: “It is a passive detection system designed to quickly detect rare and unusual adverse events and alert CDC experts to potential safety concerns. VAERS is not designed to determine whether a vaccine causes an adverse event.” On their own, these reports cannot be used to determine whether a vaccine caused or contributed to an illness or death, nor can they be used to reach conclusions about the “existence, severity, frequency, or rates of problems associated with vaccines.”

Often overlooked is the fact that the unverified reports in the VAERS system can detail any event that took place in a specified period of time after a person received a vaccine — even if the vaccine was not thought to be a factor. Investigations are only conducted on reports related to what the CDC considers a “safety signal,” i.e., “unusual or unexpected patterns of adverse events,” but updated or corrected data is not available to the public.

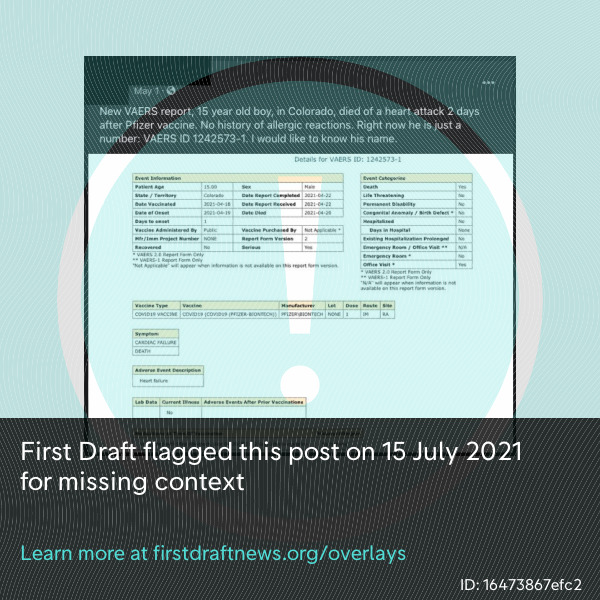

The highlighting of VAERS reports that could evoke strong emotional responses is a common tactic to stoke fears around vaccines, particularly with reports that detail a person’s injury or death and those that relate to children. At First Draft we have called to attention the importance of “emotional skepticism,” i.e., an awareness of potential manipulation through your emotions, in stopping the spread of misinformation.

Purported screenshot of a VAERS report without disclaimers

The VAERS reports are usually shared online as screenshots, often cropping out the disclaimer that the event may or may not be connected to a vaccine. Similarly, screenshots making use of reports filed by healthcare workers often leave out the part where they clarify that a vaccine was not believed to be a contributing factor to the adverse event. Without this important information, people might believe the vaccines were the cause of the death or injury. The fact that these reports are published by the CDC and FDA may also lend authority and a sense of authenticity to these false claims and narratives.

Another issue with the screenshots is that they can continue to travel and be shared online even if the report is corrected during follow-up, or removed from the VAERS database, as is the case when reports are found to be false. First Draft has identified a case of a screenshot showing a VAERS report being shared on Telegram alongside a claim implying that a 2-year-old had died as a result of the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine, despite the report no longer being searchable. Reuters quoted a CDC spokesperson as saying the report about the 2-year-old had been removed after it was found to have been fabricated. (It is worth noting that knowingly filing a false VAERS report is a federal offense.)

Telegram post with fabricated content

Furthermore, reports on the VAERS database can be downloaded and repackaged by anyone. First Draft’s research found at least three websites promoting vaccine skepticism or disinformation that have published selected VAERS reports without the necessary disclaimers. These websites, instead of VAERS, are often referenced as “proof” of possible safety concerns surrounding the vaccines, such as in a tweet by Australian MP Craig Kelly, as shown in the screenshot below. One of these websites First Draft has been monitoring is run by an organization that has received funding from and is connected to Joseph Mercola, who was named by the Center for Countering Digital Hate as one of 12 “anti-vaxxers who play leading roles in spreading digital misinformation about Covid vaccines.”

Australian MP Craig Kelly falsely attributed a VAERS report to an irrelevant website

Balancing transparency and concerns of misinformation

While the amount of online mis- and disinformation based on VAERS reports cannot be quantified, the impact from its breadth and depth is clear. In First Draft’s daily monitoring, vaccine misinformation citing VAERS appears more frequently than similarly misleading claims building upon the equivalent national reporting systems elsewhere, such as the Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN) in Australia, EudraVigilance in Europe and Yellow Card in the UK.

One reason vaccine misinformation citing VAERS seems to be more prevalent is that the reports are published on the platform in their unverified form and are viewable as is. In comparison, EudraVigilance does not publish user reports on its website and its search function, which lets people search by the name of or substance in a medicine, is not easy to navigate. Upon searching for “Covid-19 vaccine” and using the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine as an example, users are able to access an overview of the reports on possible adverse reactions by age, sex and other categories, but not the reports themselves. Similar overviews are not available on the Yellow Card website, where members of the public report on potential safety concerns about vaccines. Users must head to the website of the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for the latest weekly report based on Yellow Card entries. The reports present a breakdown of suspected but unconfirmed vaccine-related side effects that the British drug regulator is reviewing; however, they may include data from other periods of time, not just the most recent week.

The Australian health watchdog, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), also has a defense against the weaponization of DAEN user reports. Its policy is to delay publication of relevant data on DAEN for 90 days to allow medical experts to assess it. If there is no suspected link between a medicine and an adverse event, the report remains in the TGA’s internal database but is not published online. It also publishes the adverse event data in safety reports that include verification and the outcomes of investigations. These safety reports are not immune to misuse; however, the TGA has been vigilant in acting against vaccine misinformation. For instance, it publicly admonished Australian mining magnate Clive Palmer after he sponsored misleading radio advertisements implying that Covid-19 vaccines had caused 210 deaths in the country, citing TGA data. The advertisements grossly misrepresented the data — at the time of the May 27 weekly report only one death was linked to the vaccine, and as the TGA said in a June press release: “Such misinformation, in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, poses an unacceptable threat to the health of Australians.” Earlier in June, the TGA told The Guardian Australia it was considering referring similar examples of misinformation to the federal police.

When asked about VAERS reports being misinterpreted and misused to support Covid-19 vaccine misinformation, a CDC spokesperson said in a July 22 email to First Draft: “Reports of adverse events to VAERS following vaccination, including deaths, do not necessarily mean that a vaccine caused a health problem. A review of available clinical information, including death certificates, autopsy, and medical records, has not established a causal link to COVID-19 vaccines.”

It’s a case of balancing transparency and efforts to mitigate possible misinformation to ensure that the system brings more good than harm. VAERS has proven successful in delivering important public health alerts: In 1999, the first vaccine to prevent rotavirus gastroenteritis, an infection caused by the rotavirus, was withdrawn from the US market after cases of intussusception (a type of bowel obstruction) in children were reported to VAERS. This year, the system helped identify rare cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) associated with the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Covid-19 vaccine.

Now it’s time for US health authorities to work on the other side of the equation: Research shows that misinformation drives down trust in vaccines, but there may be some simple ways to mitigate this damage.

Protection against the misuse of VAERS reports

First Draft recently published advice for journalists on the effective design of overlays that can be applied to images containing misinformation to prevent amplification of inaccurate or harmful content. It’s easy for online information to be copied or screengrabbed and reused in other contexts. Ensuring VAERS reports are published with overlays or watermarks that provide disclaimers or context may be a simple way to minimize the number of people who might be misled.

Health agencies aware of the misuse of their data could also publish prebunks to lessen the effect of common misinformation narratives. As explained in First Draft’s guide to prebunking, one effective method is to take a logic-based approach, explaining the tactics used to manipulate the information. Research has shown that this approach has far-reaching benefits: If you teach people to recognize tactics, they can spot them when they are confronted with individual claims.

While the CDC has on its website answers to common questions and myths about Covid-19 vaccines, it could consider including prebunks that specifically address misinformation relating to the VAERS database and reports. This might include targeting false narratives about vaccine harms by highlighting the temporal rather than causal link between vaccines and the unverified reports.

The VAERS database was designed to be made public in 1990, long before the internet was widely available and disinformation could be propelled around the world in seconds. Early alerts to potential safety issues with vaccines or other medicines are invaluable, but if unverified and easily manipulated information is being published by two of the world’s most prominent health agencies, there must be significant efforts made to ensure public health is not placed at risk as a result.

Daniel Acosta-Ramos, Jaime Longoria, Bethan John and Lydia Morrish contributed to this report.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.