*The lessons contained in this training course, which was originally launched in the height of the pandemic in march 2020, are still very relevant now.

Alongside the rapid spread of the coronavirus, an ‘infodemic’ is also on the march. Misleading or incorrect information about the disease, how it spreads and how we can protect ourselves against it is spreading faster than the virus itself.

Whether it’s people pushing fake cures, conspiracy theories used to undermine opposition governments, hoax symptoms or funny memes, misinformation reduces trust and increases panic in our society. This complex digital environment presents challenges to content creators, technologists, policy legislators, researchers, teachers, and journalists. But we can work together to meet them.

How to use this course

We know that if you’re a journalist right now, you are rushed off your feet. You’re probably struggling to find time for lunch. We have designed the course to be ‘snackable’.

We’ve made the videos as short as possible. A couple of videos are about 10 minutes long, but most are 2-3 minutes long. We’ve also repeated key information in the text below so you can scan there if you don’t have time to watch.

The course is designed around four topics and each module is labeled with one of these four topic labels.

1) OVERVIEW: These modules focus on definitions and frameworks. There’s a lot of information packed into this section, but there are fewer tips and tricks. This is about helping you to understand information disorder and to apply it to coronavirus.

2) MONITORING: This section is designed to help you get stuck in, whether you’re looking for techniques to keep on top of all the quality information about the virus, whether you’re looking to track conspiracies and hoaxes, or if you’re looking for people talking about their personal experiences of the virus online. You can pick and choose modules by platform. Maybe you want some help searching TikTok or Instagram, or maybe you need a refresher on setting up a Twitter list. We’ve separated everything out to make it easier to navigate.

3) VERIFICATION: This section is designed to help you brush up your skills on verifying images and videos, or investigating someone’s digital footprint. Check out our case study that walks you through how we verified a video we found on social media.

4) REPORTING: This section is designed to help you word headlines, choose images and frame your reporting in ways that will slow down the spread of misinformation. How can you fill the ‘data voids’ and help explain the questions posed by your audience? It ends with a reminder to look after yourself and your sources as you do this reporting.

There is also a glossary and reading list which you can turn to at any point in the course.

We’ve designed the course so you pick your own learning journey. We hope you find it to be a valuable guide to producing credible coverage during the Coronavirus crisis

Continue to follow firstdraftnews.org for the latest news and information.

Overview

Why misinformation matters

As a species, we’re hardwired to gossip. Psychologists have shown that gossip to humans is akin to the behaviors gorillas display in groups, but while they pick fleas off each other, we connect by sharing information. Rumors, conspiracy theories, and fabricated information are nothing new. But before the age of personalized digital feeds, rumors couldn’t travel very far or very fast. Today, misleading information or deliberate hoaxes can cross international boundaries in seconds. At a critical time like this, that can become a very serious problem.

What makes people share?

Fear and love are powerful motivators. When faced with a pandemic, people share information because they’re scared and want to keep loved ones safe, be helpful, and warn others. Neuroscientists have shown that we’re more likely to remember information that appeals to our emotions.

F*** News – a four-letter word

‘F*** news’ has become a widely used term and something of a catch-all. The problem is that it doesn’t describe the full spectrum of information we find online. Information isn’t binary. It’s not a choice between fake or not fake. The term can also be used as a weapon by politicians to dismiss news outlets they don’t agree with.

Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber explain in their book The Enigma of Reason (2018), that we decide what is “true” based on social activity, and to back up existing identity and beliefs, rather than through individual deduction. Calling something ‘f*** news’ makes people choose on the basis of identity rather than fact: if you believe me, you’re on my team. If you don’t, you’re the enemy. At a time when the information that we share can mean life or death, the role of journalists and communicators is more important than ever.

The weaponization of context

We are increasingly seeing the weaponization of context. This is where genuine content is warped and reframed. Anything based on a kernel of truth is far more successful in terms of persuading and engaging people.

This is partly a response to search and social platforms becoming far tougher on attempts to manipulate their users. As they’ve tightened up on shutting down questionable accounts and become more aggressive towards misleading content (for example Facebook’s Third-Party Fact-Checking Project), agents of misinformation have learned that using genuine content, but reframed in new and misleading ways, is harder for moderation systems based on artificial intelligence to identify. In some cases, such material is deemed ineligible for fact-checking.

So to recap, now more than ever we need to be aware of how and why misinformation spreads, so we can work together to make sure that the sharing of information remains a force for good.

A framework to understand information disorder

To understand information disorder we need to understand the different types of content being created and shared, the motivations of those who create it, and how it spreads.

A common language for how we talk about this is important. We advocate using the terms most appropriate for each type of content; whether it’s propaganda, lies, conspiracies, rumors, hoaxes, hyperpartisan content, falsehoods or manipulated media. We also prefer to use the broader terms of misinformation, disinformation or malinformation (see below). Collectively, we call it information disorder (based on a report authored by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakshan in 2017).

Disinformation

When people intentionally create false or misleading information to make money, have political influence or maliciously cause trouble or harm.Misinformation

When people share disinformation but they don’t realize it’s false or misleading, often because they’re trying to help.Malinformation

When people share genuine information with an intent to cause harm. This could be personal details, sexual images published without consent, or leaked emails to damage someone’s reputation.

|

It is also useful to have a common understanding of how this content spreads. It could be:

- Shared unwittingly by people on social media, clicking retweet without checking.

- Amplified by journalists who are under more pressure than ever to make sense of and report on information emerging on the social web in real-time.

- Pushed out by loosely connected groups who are deliberately attempting to influence public opinion.

- Disseminated as part of a sophisticated disinformation campaign through bot networks and troll factories.

This common understanding of information disorder will be vital as we work together to tackle it.

The seven most common types of information disorder

Within the three overarching types of information disorder (mis, dis and mal-information), we also refer to seven main categories:

Within the three overarching types of information disorder (mis, dis and mal-information), we also refer to seven main categories:

- Satire

- False connection

- Misleading content

- Imposter content

- False context

- Manipulated content

- Fabricated content

These help us understand the complexity of this ecosystem and the shades of grey that exist between true and false. They live along a spectrum, and more than one category can apply to a specific type of content.

1. Satire

The problem in this age of information disorder is that satire can be used strategically to bypass fact checkers and to distribute rumors and conspiracies. If you’re challenged for spreading rumors, you could say that it was never meant to be taken seriously. “It was just a joke” can become an excuse for spreading misleading information.

Satire is a sure sign of a healthy democracy. It’s a powerful art form for speaking truth to power and can be more effective than traditional journalism in doing so. A good satirist exaggerates and illuminates an uncomfortable truth and takes it to often ludicrous extremes. They do so in a way that leaves the audience in no doubt about what is true and what is not. The audience recognizes the truth, recognizes the exaggeration and therefore recognizes the joke.

Satire can be a powerful tool because the more it gets shared online, the more the original context can be lost. On social media, the heuristics (the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of the world) are missing. In a newspaper, you understand what section you are looking at. You know if you’re reading the opinion section or the cartoon section. This isn’t the case online.

For example, you might be aware of The Onion, a very popular satirical site in the United States. But how many others do you know? The Wikipedia page for satirical news sites doesn’t include El Deforma, Mexico’s version of The Onion, or Revista Barcelona, a satirical political magazine from Argentina. And often when content is spread it loses its connection to the original messenger very quickly as it gets turned into screenshots or memes.

2. False connection

As part of the debate on information disorder, it’s necessary for content creators, journalists, and bloggers to recognize our own role in creating potentially problematic content.

Let’s talk about the term clickbait. Clickbait is something — usually a headline or photo — that’s designed to make readers want to click on a hyperlink, especially when the link leads to content of dubious value or interest. This ‘false connection’ is a form of information disorder. When we use sensational language to drive clicks, which then falls short for the reader when they get to the site – it’s a form of pollution.

Often, the strength of a headline can mean the difference between a handful of subscribers reading a post and it breaking through to a wider audience. Posts and news stories have to compete for the reader’s attention with cat GIFs and Netflix.

SOURCE: thesciencepost.com

For example, the satirical news website The Science Post published an article titled ‘Study: 70% of Facebook users only read the headline of science stories before commenting’ in 2018. The body of the article didn’t have any actual text, just paragraphs of “lorem ipsum” as a placeholder. But you’d only know that if you clicked through to read it. It was shared more than 125,000 times and proved the point of the headline. Most people share things without clicking through to read them.

After that, researchers at Columbia University and the French National Institute (Inria) found that we are more likely to read things curated by the people we follow. What our friends and family post or share on social media are called ‘reader referrals’ and they drive 61 per cent of the news story clicks on Twitter, according to the study. The research also found that 59 per cent of all links shared were not opened first — meaning people shared without reading past the headline.

According to one of the co-authors of the study, Inria’s Arnaud Legout, we are “more willing to share an article than read it”. The need for traffic and clicks means it’s unlikely that clickbait techniques will ever disappear, but the use of polarizing and emotive language to drive traffic can cause deeper problems. While it’s possible to use these techniques to drive traffic in the short term, there will undoubtedly be a longer-term impact on what people are willing to believe online.

3. Misleading content

What counts as misleading can be hard to define. It comes down to context and nuance: how much of a quote has been omitted? Has the data been skewed? Has the way a photo been cropped significantly changed the meaning of the image?

Some common techniques include: reframing stories in headlines, using fragments of quotes to support a wider point, citing statistics in a way that aligns with a position or deciding not to cover something because it undermines an argument.

This complexity is why we’re such a long way from having artificial intelligence flag this type of content. Computers understand true and false, but ‘misleading’ is a grey area. The computer has to understand the original piece of content (the quote, the statistic or the image), recognize the fragment and then decipher whether the fragment significantly changes the meaning of the original.

According to Reuters Institute’s Media and Technology Trends and Predictions for 2020, 85 per cent think the media should do more to call out lies and half-truths. There is clearly a significant difference between sensational hyperpartisan content and slightly misleading captions that reframe an issue. But as trust in the media has plummeted, misleading content that might previously have been viewed as harmless should be viewed differently.

4. Imposter content

Our brains are always looking for heuristics (mental shortcuts) to help us understand information. Seeing a brand that we already know is a very powerful heuristic. We trust what we know and give it credibility. Imposter content is false or misleading content that claims to be from established figures, brands, organizations, and even journalists.

The amount of information people take in on a daily basis, even just from their phones, means heuristics become even more impactful. The trust we have in certain celebrities, brands, organizations and media outlets can be manipulated to make us share information that isn’t accurate.

5. False context

This category is used to describe content that is genuine but has been reframed in dangerous ways. It is one of the most common types of misinformation that we see, and it is very easy to produce. All it takes is to find an image, video or old news story, and reshare it to fit a new narrative.

The ‘Wuhan’ market

One of the first viral videos after the Coronavirus outbreak in January 2020 showed a market selling bats, rats, snakes, and other animal meat products. Different versions of the video were shared online claiming to be from the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the new virus was first reported. However, the video was originally uploaded in July 2019, and it was shot in Langowan Market in Indonesia. It was shared widely online because it played on people’s anti-Chinese sentiment and preconceptions.

6. Manipulated content

Manipulated content is when something genuine is altered. Here, content isn’t completely made up or fabricated, but manipulated to change the narrative. This is most often done to photographs and images. This kind of manipulation relies on the fact that most of us look at images while quickly scrolling through content on small phone screens. So the content doesn’t have to be sophisticated or perfect. All it has to do is fit a narrative and be good enough to look real in the two or three seconds it takes for people to choose whether to share or not.

The Sino-Sudanese visit

On February 3, 2020, the Sudanese Minister for Foreign Affairs and the Chinese Ambassador to Sudan met to discuss the ongoing Coronavirus outbreak.

In the next couple of weeks, the photographs of that meeting were photoshopped to show the Sudanese Minister wearing a face mask. The images were shared widely on social media, including comments like “Africans don’t want to take chances with the Chinese”.

7. Fabricated content

Fabricated content is anything that is 100 per cent false. This is the end of the spectrum and the only content we can really call ‘fake’. Staged videos, made up websites and completely fabricated documents would all fall into this category.

Some of this is what we call ‘synthetic media’ or ‘deep fakes’. Synthetic media is a catch-all term for fabricated media produced using artificial intelligence. By synthesizing or combining different elements of existing video or audio, artificial intelligence can relatively easily create new content in which individuals appear to say or do things that never happened.

In this video from 2018, comedian Jordan Peele uses AI technology to make it seem like Barack Obama is speaking on camera. This technology isn’t new and has been used in cinema to bring characters to life, from Gollum in the Lord of the Rings trilogy to a young Princess Leia in Rogue One. Currently, this technology is used more widely to create non-consensual pornography — even creating full-body avatars to let people control every aspect of the human body.

At the moment synthetic media is still in its infancy. Synthetic faces can still be noticed due to small mistakes and mismatches, for example. However, it is likely that we will see examples of this used more widely in disinformation campaigns, as techniques become more sophisticated. Work is underway to counter the threat though, as scientists are developing solutions to help us detect these types of deep fakes, for example by looking at how often people blink in the videos.

The four main themes of misinformation around coronavirus

Four distinct categories of misinformation are emerging around coronavirus. They are spreading through social media and closed messaging apps in a similar pattern to the virus itself, hitting each country as the crisis grows.

The four main misinformation types:

- Conspiracies about where it came from

- Misinformation about how the virus spreads

- False and misleading information about symptoms and treatment

- Rumors about how authorities and people are responding

Where it came from

Misinformation thrives when there is an absence of verified facts. It’s human nature to try to make sense of new information based on what we already know. So, when Chinese authorities reported a new strain of coronavirus to the WHO in December, social media users flooded the information vacuum with their own theories about where it came from.

For conspiracy theorists, it was created in a lab by Microsoft founder Bill Gates as part of a globalist agenda to lower populations. Or by the Chinese government as a weapon against the United States. Or by the United States as a weapon against China.

One of the most damaging falsehoods came from a video of a market in Indonesia, posted online in June 2019. The video is shocking as it showed a range of wildlife, including bats, rats, and cats, cooked and ready to eat.

Does this video show the bat section in the #Wuhan market? Nope, this video was filmed in #Indonesia and has nothing to do with the #coronavirus #CoronaVirusFacts https://t.co/GzDDNgJyO8 pic.twitter.com/NK4nTsXoY0

— The Observers (@Observers) February 4, 2020

Dozens of YouTubers took the clip and removed the first few seconds which named the true location (Langowan, on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi) and added “WUHAN MARKET”.

Like many rumors, this was based on a kernel of truth. The seafood market in Wuhan, which stocked a wide variety of animals, was closed on January 1 and the Chinese government banned the sale and consumption of wild animals in late February, in direct response to the coronavirus.

How it spreads

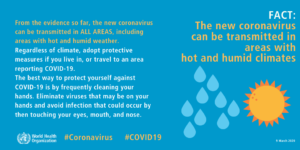

SOURCE: World Health Organisation

Many false claims are rooted in very real confusion and fear. The currency of social media is emotion, and in the coronavirus crisis, many users are trading what they think is useful advice for likes and shares.

This is especially true when it comes to the features of the virus which make it contagious. The WHO website is full of information countering false claims, including that both hot weather and cold weather kills the coronavirus (it doesn’t), that mosquitoes can transmit the disease (they can’t) and that an ultraviolet lamp will sterilize your skin (it won’t, but it might burn it).

In one example, there were claims that the “patient zero” in Italy was a migrant worker who refused to self-isolate after testing positive. Again, this holds a kernel of truth. A delivery driver was fined for doing exactly that, but there is no evidence he introduced the virus to the country. Many more malicious rumors are also circulating about how people are spreading the virus.

Elsewhere, the WorldPop project at the University of Southampton published a study in February estimating how many people may have left Wuhan before the region was quarantined. When tweeting a link to the study, they chose a picture that mapped global air-traffic routes and travel for the entirety of 2011. This “terrifying map” was then published by various Australian and British news outlets without being verified. Although the WorldPop project deleted their misguided tweet, the damage was done.

Symptoms and treatment

Bad advice about treatments and cures is by far the most common form of misinformation, and it can have serious consequences. It can stop people from getting the care they need, and in the worst-case cost lives. In Iran, where alcohol is illegal and thousands have been infected, 44 people died and hundreds were hospitalized after drinking home-made alcohol to protect against the disease, according to Iranian media.

We have also seen wild speculation on symptoms, as social media users seek to reassure themselves. A list of checks and symptoms went viral around the world in early March. Depending on where you got it from, the list was attributed to Taiwanese experts, Japanese doctors, Unicef, the CDC, Stanford Hospital Board and the classmate of the sender who had a master’s degree and worked in Shenzen. The message suggested that hot drinks and heat kill the virus and that holding your breath for 10 seconds every morning could be used to check if you had it. None of these claims were proven.

In perhaps the most famous example to date, President Trump claimed in a press conference that hydroxychloroquine, used in malaria treatments, could treat Covid-19. While there are randomly controlled trials now taking place to test the effectiveness of the medication, people are confused about whether they should try to get access to it and there are reports of shortages of the medicine as people try to stockpile. Unfortunately, others also confused the name of the drug with other substances and two days after the press conference, an Arizona couple in their sixties were hospitalized after taking chloroquine phosphate, according to Banner Health. The husband died in hospital and the wife told NBC that they had seen the press conference.

The rumors vary from the very serious, as outlined above to harmless superstitions about food and home remedies as potentially helpful. Ultimately, however frivolous, people need to realize the importance of not sharing any information unless it is from a primary source, and in almost all cases, that needs to be a medical expert.

My mum has put an onion in the corner of every room in the house because whatsapp advised her to. This is the peak of the whatsapp mother’s cult. I am unable to can lmao pic.twitter.com/KF894u0aHt

— temmy turner (@temmyoseni73) March 23, 2020

How authorities and people are responding

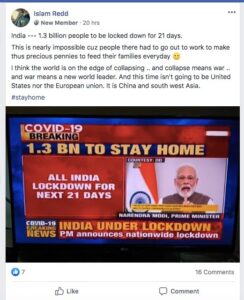

Both the pandemic and the infodemic are now global. Networked audiences on social media share content across borders, in an effort to warn each other of what’s to come.

Photos of empty shelves as people panic buy toilet paper were already circulating early in the year when people in China and Hong Kong reacted to coronavirus. An old video of a supermarket sale in 2011 was reshared and attributed to panic-buying in various cities across the UK, Spain, and Belgium. Pictures of empty shelves in US supermarkets from 2018 also claimed to show panic buying in Sri Lanka, while old footage from Mexico reported showing looting in Turkey. Examples like this spread panic from country to country.

Rumors about how different governments are reacting to the pandemic, and therefore what could be coming, also travel far and wide. Rules change from country to country, even from state to state.

With new government measures come an outbreak of misrepresented pictures, claiming the police are getting heavy-handed with those who go outside, or that the army is roaming the streets to enforce martial law.

It doesn’t help that sometimes the instructions given by governments are unclear and people have unanswered questions, like whether they can visit relatives or whether they need a permit to go outside to walk their dog.

Recently false screenshots of texts have circulated in the UK, claiming that the government is surveilling people using location data from their phones. These false rumors claim that if you go out more than once you get a text issuing a fine. Again, this is rooted in a kernel of truth — the British government did send out a text to every person in the UK saying they shouldn’t leave the house except for essential trips.

As misinformation travels around the world, we continue to see where the virus came from, how it spreads, symptoms and treatments and government response as the four main categories of misinformation.

Ten characteristics of coronavirus misinformation

Monitoring

How to approach monitoring, keywords and advanced search

Smart searches cut through social media chatter by finding precise snippets of information based on keywords. When searching for newsworthy content online, you’ve got to know exactly what you’re looking for and have the skills to find it. Using the right keywords to search in the right places is key. When thinking of keywords:

- Think about how people speak (include swear words, misspellings, slang, etc).

- Connect keywords using Boolean search queries.

- Include first person terms (my, I’m, me, mine) to find eyewitness content.

- Think of platforms as sources. Different conversations happen in different communities.

- Remember that keywords evolve.

How to write a basic Boolean search query

This is where Boolean search queries help. These strings of words allow you to cut through the usual social media chatter by upgrading a default search to a multifaceted, specific search to find more precise snippets of information.

In this quick guide, we run through the basics of what you need to know to search social media for effective newsgathering.

Boolean searches help you to specify exactly what you are looking or not looking for. For example, let’s say you’re searching for posts during a breaking news event, such as the Notre Dame fire. You want to search for Notre Dame, but you won’t want posts about the Disney film.

A boolean search will allow you to include posts that mention “Notre Dame”, but exclude ones about the Disney film to refine your search results and find the information you’re after.

This is possible with ‘operators’, which allow you to combine multiple keywords. There are three operators for basic searches: AND, OR, and NOT.

AND

AND allows you to narrow your search to only retrieve results that combine two or more terms. For example, you might want to search for “Notre Dame” and fire.

OR

OR allows you to broaden your search to retrieve results connecting two or more similar terms. This can be good for misspellings and typos. In the case of Notre Dame, you could search for “Notre Dame” OR “Notre Dam”. This will retrieve all results containing either phrase.

Key points:

- Operators (AND, OR ) must be written in capitals, or they won’t work

- If you’re searching for phrases (terms made up of multiple words) then you have to put them in quotation marks (eg “Coronavirus vaccine”)

- You won’t be able to find information that has been made private by a user

How to add complexity to your search

Grouping sections together is most useful for long and complicated searches. It will reduce the risk of the search breaking and is simpler to manage. Also known as nesting, this approach also allows you to search for several variations of your search terms at once. To group parts of a search together, you simply use brackets or parentheses.

For example, if you’re looking to find various coronavirus related hashtags and misspellings you would write:

( coronavirus OR caronavirus OR coronavirusoutbreak OR coronoavirus)

The parts of your search that are inside parentheses will be prioritized by the database or search engine to retrieve a broader set of results.

Sample Boolean search queries for monitoring coronavirus

Here are samples of Boolean searches the First Draft team is using to monitor issues in relation to coronavirus. We would recommend that you add some additional keywords that are specific to your area or audience.

Covid General Terms

Note: We feel obligated to mention that our inclusion of certain search terms is due to their prevalence on social platforms, we certainly do not endorse racist terminology.

Coronavirus OR COVID-19 OR covid OR Sars-Cov-2 OR “corona virus” OR “china flu” OR “wuhan flu” OR wuhanvirus OR “china virus” OR “chinavirus OR caronavirus” OR coronovirus

Elections and Covid

(Coronavirus OR COVID-19 OR covid OR Sars-Cov-2 OR “corona virus” OR “china flu” OR “wuhan flu” OR “china virus” OR “chinavirus OR caronavirus) AND (voting OR voter OR vote OR votes OR voters OR election OR elections OR primary OR primaries OR polls OR “polling place” OR “polling location” OR ballot OR ballots)

Census and Covid

Note: This search contains a proximity operator, which returns results only if the words are near each other. The notation for a proximity search is different depending on the search engine. The notation we have used below is formatted for Google.

(Coronavirus OR COVID-19 OR covid OR Sars-Cov-2 OR “corona virus” OR “china flu” OR “wuhan flu” OR “china virus” OR “chinavirus” OR caronavirus) AND (census OR questionnaire OR door AROUND(3) knock OR door AROUND(3) knocking OR door AROUND(3) knocked)

Covid Questions

Note: This search will likely return false positives, but it has proven interesting to the First Draft team regardless:

(Coronavirus OR COVID-19 OR covid OR Sars-Cov-2 OR “corona virus” OR “china flu” OR “wuhan flu” OR “china virus” OR “chinavirus” OR caronavirus) AND (“I have a question” OR “should I” OR “can I” OR “what happens if”)

Monitoring with Twitter Lists

Twitter’s list function is a great way to collect and monitor Twitter accounts of interest.

Twitter Lists let you:

- Monitor groups of accounts, organizations by topic, etc

- See an account’s content without following them

- Follow or subscribe to other people’s lists

- Share lists of useful accounts with colleagues

How to find Twitter Lists on Twitter.com

1. To create a list, first open your Twitter account and navigate to the logo on the left hand panel that looks like a document with a few lines of text.

Source: Twitter.com/WHO

2. This will bring you to a screen with all the lists you have created, subscribed to, or are a member of. In the top right corner, you’ll notice the same document logo, this time with a plus sign — click it!

3. Here you can give your list a name and description. It’s also where you can choose to make your list private (viewable only to you), or public (listed on your profile and searchable).

4. After you fill out the boxes, click next and you’ll be brought to a search bar where you can type in account names to begin adding to your list.

5. Alternatively, if you’re exploring Twitter and find an account you’d like to add to an existing list, choose the three dots next to the follow button on their profile, and click “add/remove from lists.”

6. Once a list has been created, you can click on it to explore a feed that consists only of content tweeted or retweeted by the list members.

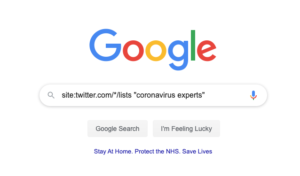

How to search for Twitter lists on Google

There’s a wealth of Twitter Lists publicly available that might be useful to your work. To find them, choose the “View Lists” option below “add/remove from Lists,” seen in the above screenshot.

|

SOURCE: google.com |

There is no native way to search for Twitter Lists by topic on Twitter, but you can use this Google shortcut to find public Twitter Lists; site:twitter.com/*/lists “search term”

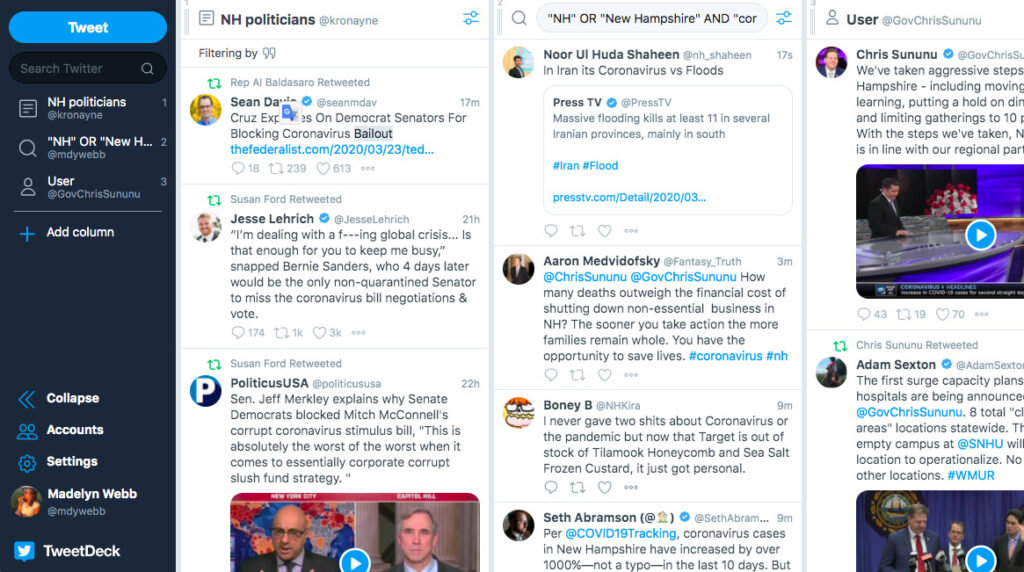

Displaying Twitter lists on Tweetdeck

Tweetdeck is a free tool widely used by journalists and researchers to monitor and newsgather on Twitter.

In the Tweetdeck interface you can monitor several columns with different content in one place. Columns can consist of Twitter lists, users, keyword searches, mentions, likes, and more.

In the example below, we are monitoring a list (NH politicians), a keyword search, and a user (Governor Chris Sununu). To access Tweetdeck all you need is a Twitter account. You simply login with your Twitter credentials, click the “Add column” option on the left hand side, choose what you wish to explore, and begin monitoring.

How to copy Twitter lists

Twitter List Copy, founded by a graduate student is a useful way of being able to copy the lists of someone else’s account.

|

SOURCE: Twitter Copy List |

Sign into your own twitter account on the site and then enter the account handle of the owner of the Twitter List you wish to copy.

The dropdown will provide all of the lists that account has set up. Simply select the one you wish to copy. The tool will only allow you to copy this into one of your existing Twitter lists so you may wish to create a blank list with the name you want to use before going to this website.

CrowdTangle Live displays for every country

CrowdTangle is a social analytics tool owned by Facebook. Their main portals require sign-up, but everyone can access their Public Live Displays. It’s a quick, visual way to see how information on coronavirus is being spread on social media.

Public Live Displays are organized by region and country and show content from local media, regional World Health Organization pages, government agencies, and local politicians as well as social media discussion from Facebook, Instagram, and Reddit.

Each Public Live Display shows Covid-19 related posts in real-time, sorted by keyword, with public pages and accounts for each region.

Do you want to know what Corona content is trending in your country on Facebook? @Crowdtangle launched publicly available Live Displays. You don't need an account to use them: https://t.co/9iJDltb22C

— Johanna Wild (@Johanna_Wild) March 25, 2020

Using RSS feeds to stay updated

RSS, or Really Simple Syndication, is an easy way to get new content from the websites or blogs you’re interested in, all in one feed. Instead of checking multiple sites every day, simply install an RSS reader and have any fresh content served up to you.

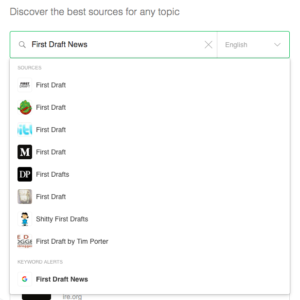

Registering with Feedly

There are several RSS reader applications available, but we recommend Feedly for its usability. First, you’ll need to register as a Feedly user. Once you’ve created your account, you can begin creating RSS feeds, organized to suit your needs. You could choose to have different feeds for different topics or build feeds for particular sources, such as government authorities or news sites. What you choose to include in your feeds is totally up to you.

|

SOURCE: Feedly |

Setting up feeds

To set up an RSS feed, go to Feedly, and click “create a feed.” You’ll be asked to give the new feed a title and then you can begin populating it with what you want to track. Feedly allows you to input a specific website, keyword, or RSS link.

Following a website

If you want to see all the new content from a website on your feed, choose the site of interest, click on the “Follow” button, and add it to the relevant feed.

|

SOURCE: Feedly |

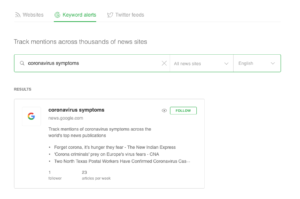

Following a keyword or phrase

Keywords function very much like Google alerts, so you can choose this option if you would like all mentions of a keyword or set of keywords delivered to your feed. If you’re interested in a specific phrase, be sure to input it using quotation marks.

You can also use keyword alerts to monitor mentions of a publication, a person or a topic regardless of what website published it.

Following an RSS link

If you type in a website of interest and it’s not showing up on Feedly, but you know they have RSS, you can add /RSS to the end of the URL, and input that link into Feedly to add it to your custom RSS feeds.

Spotting patterns and templates

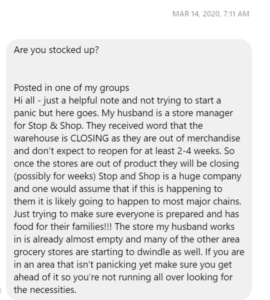

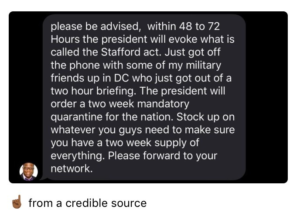

During elections we see the same techniques being used. For example, the trick of circulating information with the wrong polling date has been seen in almost every country. Once malicious actors know something works, it’s easier to re-use the idea than starting from scratch and risk failure. The same is happening with coronavirus. We keep seeing the same patterns of stories and the same types of content traveling from country to country as people share information. These become ‘templates’ that are replicated across languages and platforms.

While you can find these ‘template’ examples on all platforms, during this coronavirus pandemic, we’re seeing a lot of these cut and paste templates on closed messaging apps and Facebook groups. It’s therefore hard to get a true sense of the scale of these messages, but anecdotally we’re seeing many people reporting similar wording and images.

The problem is that most of these are anchored in a grain of truth that makes them spread faster because it’s harder to determine what part of the information is false. Whether it’s scams, hoaxes, or the same video being shared with the same wrong but translated context, be aware.

Lockdowns

Around the world, concerns are spreading about imminent military lockdowns, national quarantines and the rolling out of martial law following announcements for various stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders. Different countries have different rules, and sometimes different cities have passed different ordinances at different times. This adds to the general confusion and can lead to people sharing information to try to make sure their loved ones are safe and prepared by sharing information.

For example, several Telegram broadcast channels and groups have shared clips of tanks on trains, Humvees, and other military vehicles driving through towns and cities. One video, shared to a popular Telegram channel that has thousands of subscribers, claimed they had a recording of the “Military rolling into NYC”. However, the creator of the video says he was in FedExField, which is in Washington, D.C.

We saw the same kind of videos being shared on social media in Ireland and the UK, of alleged tanks on the street, road blockages by police and the military around mid-March. The videos were, for the most part, older and re-shared online out of context, or they were images from road accidents where the police had arrived. But because they fit into different online narratives of what was happening in other countries, people re-shared to warn each other of what was possibly on the horizon.

|

|

Because people are trying to keep each other safe, there are similar versions of rumors of lockdowns calling for people to make sure they’re stocked up and ready.

|

|

However, these messages leave out essential information and capitalize on people’s fears. The reality for many cities on lockdown is that many essential shops are still open, people can go outside to exercise or buy food, and messages calling for people to be prepared only fuel panic shopping.

On Facebook, a viral post from an Italian makeup influencer told two million followers that Americans were in a race to buy weapons in New York and other large metropolitan areas and that she had “fled” the city out of fear for her safety.

As countries and cities around the world take their own measures, we see the same kind of reaction online over and over again. People are worried about how to stay safe and prepared.

|

|

|

|

Sometimes the confusion happens in the information vacuum between when people spot things happening around them and the time it takes for governments and institutions to explain what is happening.

|

|

| A social post online reporting the presence of military airplanes at London City Airport on March 25th, 2020. | A twitter post by the UK’s Army in London explaining the presence of military vehicles on the street on March 27th, 2020. |

If you see something that seems suspicious, plug it into a search engine. It’s very likely the same content has been debunked by a fact-checker or newsroom in another part of the world. BuzzFeed has a very comprehensive running list of hoaxes and rumors you can find here.

The ethics of monitoring closed groups

As this pandemic has moved across the globe, we’re seeing a great deal of conversation related to the virus moving to private messaging groups and channels. This might be because people feel less comfortable sharing information in public spaces at a time like this, or it might be that people are turning to sources they feel they know and trust as fear and panic increases.

One of the consequences of this shift is that rumors are circulating in spaces that are impossible to track. Many of these spaces are invite-only, or have end-to-end encryption, so not even the companies know what is being shared there.

But is there a public interest for journalists, fact-checkers, research and public health officials to join these spaces to understand what rumors are circulating so they can debunk them? What are the ethics of reporting on material you find in these spaces?

There are ethical, security and even legal challenges to monitoring content in closed spaces, as outlined by First Draft’s Essential Guide to Closed Groups. Here’s a shorter round-up based on some of the key questions journalists should consider:

Do you need to be in a private group to do coronavirus research and reporting?

Try looking for your information in open online spaces such as Facebook Pages before joining a closed group.

What is your intention?

Are you looking for rumors on cures and treatments, sources from a local hospital or leads on state-level responses? What you need for your reporting will determine what sort of information to look for and what channels or groups to join.

How much of your own information will you reveal?

Some Telegram groups want participants, not lurkers, and some Facebook Groups have questions you need to answer before you can join. How much will you share honestly?

How much will you share from these private sources?

People are looking for answers because they are afraid. If the group is asking about lockdowns and national travel bans, and the answers being shared are creating panic and fear, how will you share this publicly? Consider again your intent and if that community has a reasonable expectation of privacy before sharing screenshots, group names and personal identifiers such as usernames. Will publishing or releasing those messages harm the community you’re monitoring?

What’s the size of the closed group you are looking to join?

Facebook, WhatsApp, Discord, WeChat and Telegram have groups and channels of varying sizes. The amount of content being shared depends more on the number of active users than overall numbers. Observe how responsive the group is before joining.

If you are looking to publish a story with the information gathered, will you make your intention known?

Consider how this group may respond to a reporter, and how much identity-revealing information you are willing to publish from the group.

If you do reveal your intention, are you likely to get unwanted attention or abuse?

First Draft’s essential guide on closed message apps shows that journalists of color and women, for example, may face additional security concerns when entering into potentially hostile groups. If you decide to enter the group using your real identity, to whom will you disclose this information? Just the administrator or the whole group?

How much will you share of your newsgathering processes and procedures?

Will revealing your methodology encourage others to enter private groups to get ‘scoops’ on misinformation? Would that negatively impact these communities and drive people to more secretive groups? Will you need to leave the group after publication, or will you continue reporting?

Ultimately, people will search for answers wherever they can find them. As journalists, it’s important that those data voids are filled with facts and up-to-date information from credible sources. The question is how to connect community leaders with quality information, so fewer rumors and falsehoods travel in these closed spaces.

Reliable sources for coronavirus information

The infodemic that’s accompanying the coronavirus outbreak is making it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it. Knowing where to turn for credible advice is vital, so here we’ll list some reliable sources.

Remember, not all research is created equal. Just because something is presented in a chart or a table doesn’t mean the data behind it is solid.

Reuters looked at scientific studies published on the coronavirus since the outbreak began. Of the 153 they identified, 92 were not peer-reviewed despite including some pretty outlandish and unverified claims, like linking coronavirus to HIV or snake-to-human transmission. The problem with “speed science”, as Reuters called it, is that people can panic or make wrong policy decisions before the data has been properly researched.

|

SOURCE: Reuters, 2020. Speed Science: The risks of swiftly spreading coronavirus research |

Here are some of the best places to go for reliable advice and updates:

Government departments and agencies

These government departments provide updates on the number of coronavirus cases, government activities, public health advice, and media contacts:

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China

- Italian Department of Health

- South Korea’s Ministry of Health & Welfare

INGOs and NGOs

The below non-governmental organizations provide global and regional data and guidance on coronavirus:

- Communications contacts in WHO headquarters (Geneva)

- Communications officers in the WHO regions

- World Bank media contacts

- International Society for Infectious Diseases (supporting health professionals, NGOs, and governments to prevent, investigate, and manage infectious disease outbreaks).

- Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (a global partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organizations).

- American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (a community of researchers, clinicians, and professionals aiming to advance global health).

Academic institutions

These organizations and institutions provide research and data on coronavirus, as well as expert commentary.

- Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University

- Royal College of Physicians in the UK

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- School of Public Health, University of Michigan

- London School of Economics

The need for emotional skepticism

People like to feel connected to a ‘tribe’. That tribe could be made up of members of the same political party, parents that don’t vaccinate their children, activists concerned about climate change, or those belonging to a certain religion, race or ethnic group. Online, people tend to behave in accordance with their tribe’s identity, and emotion plays a big part in that, particularly when it comes to sharing.

Neuroscientists know that we are more likely to remember information that appeals to our emotions: stories that make us angry, sad, scared or laugh. Social psychologists are now running more experiments to test this question of emotion, and it seems that heightened emotionality is predictive of an increased belief in false information. You could argue that the whole planet is currently experiencing ‘heightened emotionality’.

False and misleading stories spread like wildfire because people share them. Lies can be very emotionally compelling. They also tend to be grounded in truth, rather than entirely made up. We are increasingly seeing the weaponization of context: the use of genuine content, but of a type that is warped and reframed. Anything with a kernel of truth is far more successful in terms of persuading and engaging people.

In February, an Australian couple was quarantined on a cruise ship off the coast of Japan. They developed a following on Facebook for their regular updates, and one day claimed they ordered wine using a drone. Journalists started reporting on the story, and people shared it. The couple later admitted that they posted it as a joke for their friends.

This might seem trivial, but mindless resharing of false claims can undermine trust overall. And for journalists and newsrooms, if readers can’t trust you on the small stuff, how can they trust you on the big stuff? So a degree of emotional skepticism is critical. It doesn’t matter how well trained you are in verification or digital literacy, it doesn’t matter whether you sit on the left or right of the political spectrum. Humans are susceptible to misinformation. During a time of increased fear and uncertainty, no-one is immune, which is why an awareness of how a piece of information makes you feel, is the most important lesson to remember. If a claim makes you want to scream, shout, cry, or buy something immediately, it’s worth taking a breath.

Verification

The 5 Pillars of Verification

Verification can be intimidating, but through repetition, persistence, and using digital investigation tools with a little creativity, it can be made easier. There is no recipe for verifying content online or a set of steps that work every time. It’s about asking the right questions and finding as many answers as possible.

Whether you’re looking at an eyewitness video, a possible deepfake, or a meme, the basic checks to run are the same. The more you know about each pillar, the stronger your verification will be.

-

- Provenance: Are you looking at the original piece of content?

- Source: Who captured the original piece of content?

- Date: When was the piece of content captured?

- Location: Where was the piece of content captured?

- Motivation: Why was the piece of content captured?

Establish a verification workflow

Now that you know what questions to ask, here are three key steps for any verification workflow:

-

- Document everything. It’s easy to lose crucial pieces of information. Documenting is also important for the transparency of your verification. Take screenshots or use a backup to a service like Wayback Machine.

- Set up a toolbox. Keep lists of tools, bookmark them and share with colleagues. Don’t waste time trying to remember what that website that does reverse image searches is called. We have a Basic Verification Toolkit which you can bookmark.

- Don’t forget to pick up the phone. Good old fashioned analog journalism can sometimes be the quickest way to verify something.

Verification is vital but beware of the rabbit hole. Often verification takes minutes, other times it can lead you down an endless path. Know when it’s time to call off the chase.

Verify images with reverse image search

A picture is worth a thousand words, and when it comes to disinformation it can also be worth a thousand lies. One of the most common types of misinformation we see at First Draft looks like this: genuine photographs or videos, that have not been edited at all, but which get reshared to fit a new narrative.

But with a few clicks, you can verify these types of images when they are shared online and in messaging groups.

Just like you can “Google” facts and claims, you can ask a search engine to look for similar photos and even maps on the internet to check if they’ve been used before. This is called a ‘reverse image search’ and can be done with search engines like Google, Bing, Russian website Yandex, or other databases such as TinEye.

In January, Facebook posts receiving thousands of shares featured the photograph (embedded below) and claimed the people in the photo were coronavirus victims in China. A quick look at the architecture shows that it looks very European, which might raise suspicion. Then if we take the image, run it through a reverse image search engine, and look for previous places it has been published, we find the original from 2014. It was an image, originally published by Reuters, of an art project in Frankfurt, which saw people lie in the street in remembrance of the victims of a Nazi concentration camp.

|

A photograph of an art project in 2014 in Germany that got shared on Facebook in 2020 to falsely claim the people in the photo were coronavirus victims in China.SOURCE: Kai Pfaffenbach Reuters |

Here’s some tools you can use:

- Desktop: RevEye’s Plugin allows you to search for any image on the internet without leaving your browser.

- Phone: TinEye allows you to do the same thing on your phone

The whole process takes a matter of seconds, but it’s important to remember to check any time you see something shocking or surprising.

Using geolocation to determine where a photo or video was taken

On most social networks, when you upload a post, image or video, it will ask you where you are. It will often help you by taking your phone’s GPS position and suggesting your location. But you can override that suggestion. That means that anytime you see a post on social media, you can’t trust the location listed. So you need to do your own sleuthing.

We all have powerful observation skills, which, when combined with and a bit of Googling, can help us quickly decide if a photo is what it claims to be. Take the tweet below from The New York Post. It’s about the first case of confirmed coronavirus diagnosis in Manhattan. Alessandra Biaggi, an American Senator that represents the area, quickly pointed out the photograph they used was taken in Queens. How did she know?

|

|

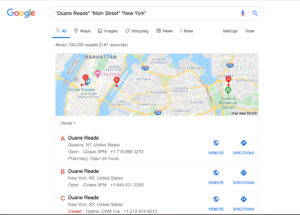

In this case, we can use the street and store signs in the photo to find the same spot on a map. Search for “Duane Reade” “Main Street” “New York” and you will be presented with three options.

|

SOURCE: GOOGLE.COM |

Flushing in Queens is a good place to start as it is such a diverse neighborhood. By going to that Main Street Duane Reade in Google Maps, it’s then possible to drop the little yellow man onto the roads to get the Street View version. From there you can see the same buildings from the same perspective as the photographer.

If the photo is outdoors, look for clues in the architecture, street signs, what people are wearing, what side of the road cars are driving on, names of businesses etc. What can you search for and verify? Can you look up the businesses? Can you find that same spot on a map?

If the photo is indoors, you can look at wall plugs, what language the posters are in, the weather and anything on TV.

To practice your observational skills, take our interactive observation challenge. And if you’re a pro, try our advanced geolocation challenge.

Verifying videos using thumbnails and InViD

Whenever you upload a video to the internet, it creates a thumbnail, or screenshot, to show as a preview. You can manually change it, but most people don’t. Just like you can use a reverse image search to find out if a photograph has been published on the internet before, you can use thumbnails to see if a video has been previously posted online.

|

Video showing people caught farting by thermal cameras was originally made in 2016SOURCE: Banana Factory |

For example, this silent but deadly video claimed to show people caught farting by thermal cameras that were monitoring temperature for possible coronavirus patients. But after reverse image searching screenshots of the video, you can find that the original is a joke video from 2016. The video was created by an online group called Banana Factory, who added the offending ‘clouds’ by computer before it was shared by websites like LadBible and Reddit.

Around the world, fact-checkers have been verifying videos that falsely claim to show the symptoms or impact of coronavirus, all of which are just old videos reshared with a new caption. As WHO chief Dr. Tedros said, this kind of scaremongering can have a more dangerous impact on the world than the disease itself, causing panic and draining resources which could be better used to deal with real-world problems.

Using reverse image search, you can take several thumbnails from any video and check whether it’s been posted on the Internet before. InVid’s video verification plugin has some very effective tools to verify images and videos, and their “Classroom” section is filled with other tutorials and goodies. So before you share that clip with your chat groups, check you’re not getting fooled.

How to verify accounts using digital footprints

Social media is currently full of people who claim to have reliable medical advice. There are ways to check if someone is who they claim to be through their social media profile. Follow these basic techniques for digital footprinting and verifying sources online:

An example and three simple rules to follow

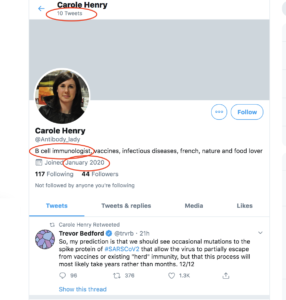

|

SOURCE: twitter.com |

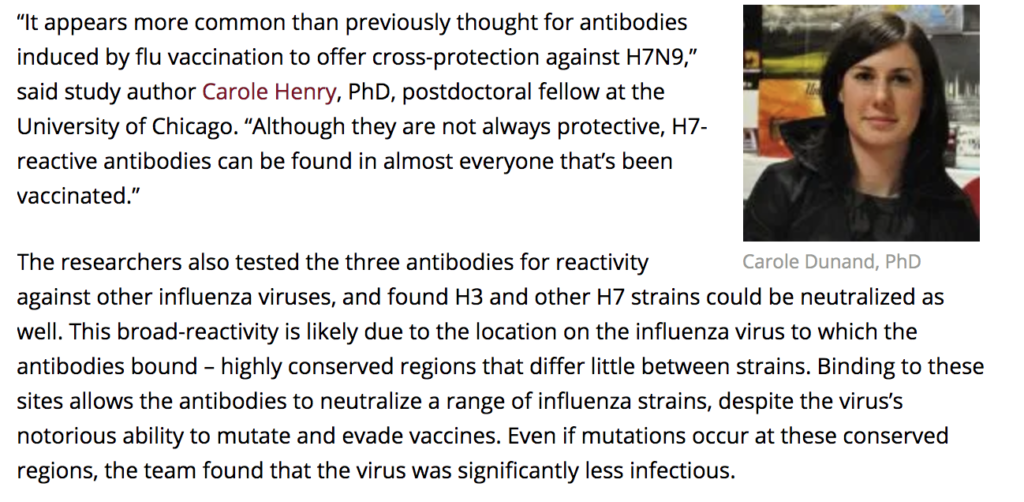

Let’s practice by verifying the Twitter profile of a medical professional: Carole Henry. Carole has been tweeting about Covid-19, and her bio says that she is a “B cell immunologist.”

But how can we be sure of her credentials? The profile doesn’t give us a lot of information: it doesn’t have the blue “verified” check; it doesn’t link to a professional or academic website; she only joined Twitter in January 2020; and she only has 10 tweets.

With a little searching, we can actually learn a lot about her.

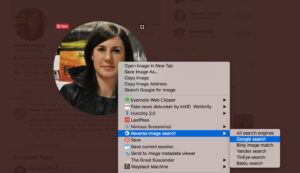

Rule #1: Reverse image search the profile picture

|

|

Reverse image searches are powerful because they give you a lot of information in a matter of seconds. We recommend you do reverse image searches with the RevEye Reverse Image Search extension, which you can download for Google Chrome or Firefox.

Once RevEye is installed, click on Carole’s profile picture to enlarge it. Next, right click the image, find “Reverse Image Search” in the menu, and select “Google search.”

A new tab should pop up in your browser. If you scroll to the bottom, there is a helpful section titled “Pages that include matching images.” Look through these.

|

|

One of the first results looks like an article from the medical school of the University of Chicago. |

|

|

Scrolling down, we can see that same picture of Carole, and a quote that says she is a postdoctoral fellow at the university. Below the picture, it says her name is “Carole Dunand.” That is an interesting piece of info that we can use later. |

SOURCE: LinkedIn |

The reverse image search results also lead us to a Linkedin profile, that says she is a staff scientist at the University of Chicago with 10 years of experience as an immunologist. |

Rule #2: Check primary sources

|

SOURCE: Google.com |

Remember the journalism rule-of-thumb: always check primary sources when they are available. In this case, if we want to confirm that Carole Henry is a scientist at the University of Chicago, the primary source would be a University of Chicago staff directory. A quick Google search for “Carole Henry University of Chicago” leads to a page for the “Wilson Lab.” The page has a University of Chicago web address, and also lists her as staff.

Rule #3: Find contact information

|

SOURCE: http://profiles.catalyst.harvard.edu/ |

It may be unlikely, but there is always a chance that the original Twitter profile we found is just someone posing as Carole Henry from the University of Chicago. For a truly thorough verification, look for contact information so you can reach out to the source.

Remember that other name we found – “Carole Dunand”? A search for “Carole Dunand University of Chicago” leads right to another staff directory, this time with her email address.

Here’s some other questions that will help you verify accounts

- When was the account created?

- Can you find that person online anywhere else?

- Who else do they follow?

- Are there any other accounts with that same name?

- Can you find any contact details?

A verification case study

Here we take a look at a case study involving a video posted on Twitter that claims to show an Italian coronavirus patient escaping from a hospital. We discover that the clip is not all it seems by applying our verification process and the five pillars of provenance, source, date, location and motivation.

Reporting

Understanding Tipping Points

When you see mis- and disinformation, your first impulse may be to immediately debunk – expose the falsehood, tell the public what’s going on and explain why it’s untrue. But reporting on misinformation can be tricky. The way our brains work means that we’re very poor at remembering what is true or false. Experimental research shows how easy it is for people to be told something is false, only for them to state it’s true when they’re asked about it at a later point. There are best practices for writing headlines, and for explaining that something is false, which we explore in the next section. Unfortunately, even when well-intentioned reporting, can add fuel to the fire and bring greater exposure to content that might have otherwise faded away. Understanding the tipping point is crucial in knowing when to debunk.

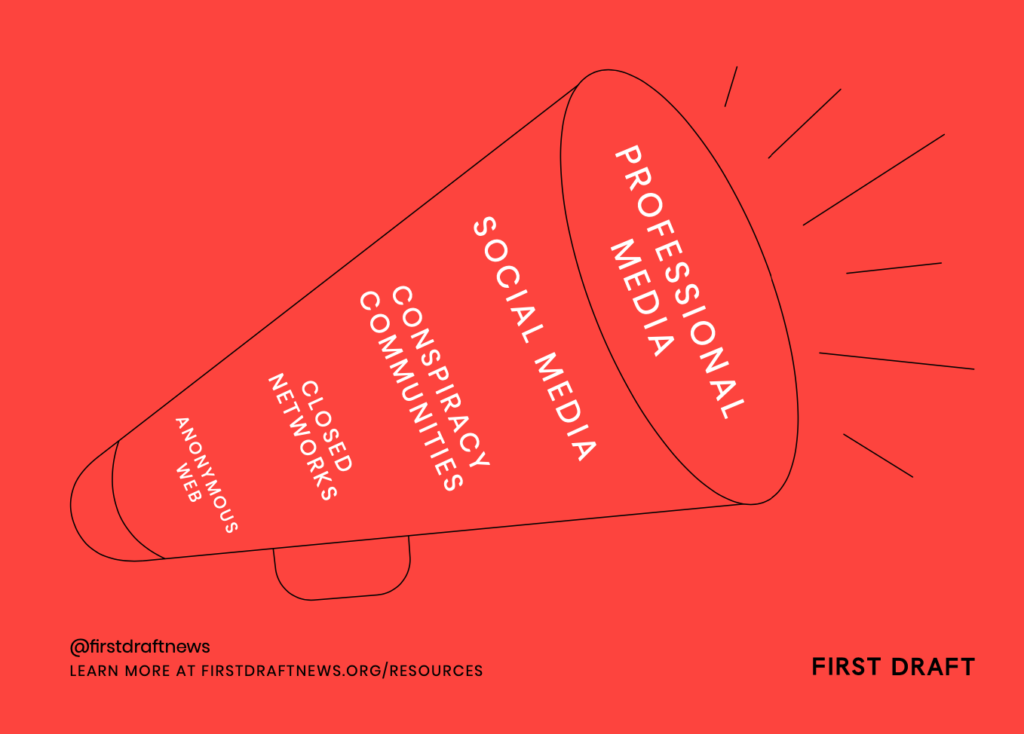

The Trumpet of Amplification

The illustration below is a visual reminder of the way false content can travel across different social platforms. It can make its way from anonymous message boards like 4Chan through private messaging channels on Telegram, WhatsApp and Twitter. It can then spread to niche communities in spaces like Reddit and YouTube, and then onto the most popular social media platforms. From there, it can get picked up by journalists who provide additional oxygen either by debunking or reporting false information.

Syracuse University professor Whitney Phillips has also written about how to cover problematic information online. Her 2018 Data & Society report, The Oxygen of Amplification: Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online, explains: As Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis noted in their 2017 report, Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online, for “manipulators, it doesn’t matter if the media is reporting on a story in order to debunk or dismiss it; the important thing is getting it covered in the first place.”

“It is problematic enough when everyday citizens help spread false, malicious, or manipulative information across social media. It is infinitely more problematic when journalists, whose work can reach millions, do the same.”

The Tipping Point

In all scenarios, there is no perfect way to do things. The mere act of reporting always carries the risk of amplification and newsrooms must balance the public interest in the story against the possible consequences of coverage.

Our work suggests there is a tipping point when it comes to covering disinformation.

Reporting too early… |

Reporting too late… |

|---|---|

| can boost rumors or misleading content that might otherwise fade away. | means the falsehood takes hold and can’t be stopped – it becomes a “zombie rumor”, that just won’t die. |

Some key things to remember about tipping points:

- There is no one single tipping point – The tipping point can be measured when content moves out of a niche community and starts moving quickly on one platform, or crosses onto others. The more time you spend monitoring disinformation, the clearer the tipping point becomes – which is another reason for newsrooms to take disinformation seriously.

- Consider the spread – This is the number of people who have seen or interacted with a piece of content. It can be tough to quantify with the data available, which is usually just shares, likes, retweets, views, or comments. But it is important to try. Even small or niche communities can seem more significant online. If a piece of content has very low engagement, it might not be worth verifying or writing about.

- Collaboration is key – Figuring out the tipping point can be tough, so it could be a chance for informal collaboration. Different newsrooms can compare concerns about coverage decisions. Too often journalists report on rumors for fear they will be ‘scooped’ by competitors – which is exactly what agents of disinformation want.

Some useful questions to help determine the tipping point:

- How much engagement is the content getting?

- Is the content moving from one community to another?

- Is the content moving across platforms?

- Did an influencer share it?

- Are other journalists and news media writing about it?

Determining the tipping point is not an exact science, but the key thing is to pause and consider the above for debunking or exposing a story.

The importance of headlines

Headlines are incredibly important as they are often the only text from the article that readers see. In a 2016 study, computer scientists at Columbia University and the Microsoft Research-Inria Joint Centre estimated that 59% of links mentioned on Twitter are not clicked at all, confirming that people share articles without reading them first.

Newsrooms reporting on disinformation should craft headlines carefully and precisely to avoid amplifying the falsehood, using accusatory language or reducing trust.

Here we will share some best practice for writing headlines when reporting on misinformation, based on the Debunking Handbook by the psychologists John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky and his colleagues.

Problem |

Solution |

| Familiarity Backfire Effect By repeating falsehoods in order to correct them, debunks can make falsehoods more familiar and thus more likely to be accepted as true. |

Focus on the facts Avoid repeating a falsehood unnecessarily while correcting it. Where possible, warn readers before repeating falsehoods. |

| Overkill Backfire Effect The easier information is to process, the more likely it is to be accepted. Less detail can be more effective. |

Simplify Make your content easy to process by keeping it simple, short and easy to read. Use graphics to illustrate your points. |

| Worldview Backfire Effect People process information in biased ways. When debunks threaten a person’s worldview, those most fixed in their views can double down. |

Avoid ridicule Avoid ridicule or derogatory comments. Frame debunks in ways that are less threatening to a person’s worldview. |

| Missing Alternatives Labeling something as false, but not providing an explanation often leaves people with questions. If a debunker doesn’t answer these questions, people will continue to rely on bad information. |

Provide answers Answer any questions that a debunk might raise. |

Using and sharing images mindfully

Images are hugely powerful and need to be used mindfully. It’s important to carefully consider any photos or images and provide context and to try and steer clear of stock images that could feed stereotypes.

We also need to think very carefully about context, particularly when it comes to embedding social media posts that show members of the public. That image might only have been meant for a small number of people, and the more it gets amplified and shared, the more the original context gets lost. Even images used by credible news organizations that are carefully presented in context can still be taken, used out of context and circulated far and wide.

Fuelling xenophobia

Before using a photo of an Asian person wearing a face mask, for example, ask how this image is relevant to your story. Are the subjects of your story Asian? Is your story about the efficacy of face masks in preventing the spread of the virus? The Asian American Journalists Association has issued helpful guidance on avoiding fuelling xenophobia and racism in Covid-19 reporting.

Causing panic

The same goes for images that could cause undue panic. Would your use of an image of people wearing hazmat suits cause readers alarm? Would using an image of an ambulance with an empty trolley waiting to enter a house create fear? It’s important to think about the impact of header images when concerns are rising about the impact of the virus.

Here are some guidelines to follow:

- Avoid images that could increase panic and use images that reinforce the behavior we want to see emulated

- Avoid images that rely on stereotypes

- Be wary of embedding social media posts and images that could significantly impact those involved

Filling data voids

Michael Golebiewski and danah boyd, both connected to Microsoft Research first used the term “data void” to describe search queries where “the available relevant data is limited, non-existent, or deeply problematic.”

In breaking news situations, write Golebiewski and Danah Boyd of Microsoft Research and Data & Society, readers run into data voids when “a wave of new searches that have not been previously conducted appears, as people use names, hashtags, or other pieces of information” to find answers.

Newsrooms should think about Covid-19 questions or keywords readers are likely searching for, look to see who is creating content around these questions, and fill data voids with quality content.

This is the counterpart to figuring out what people are searching for using Google Trends. Reverse engineer the process: when people type in questions related to coronavirus, what do they find?

It’s important to figure out what Covid-19 questions readers are asking, and fill data voids with service journalism. For example, below is a screenshot of the Google results page for the query “can I catch coronavirus from packages”.

Readers searching for the answer will find some news stories about the US Senate’s coronavirus emergency spending, which is presumably not what they are looking for.

Using Google trends to find the questions being asked

|

| SOURCE: trends.google.com |

Google Trends lets you monitor public searches across the world and see the kind of information and answers that the public is looking for.

Google has produced a dedicated trends dashboard showing information and data around search terms related to coronavirus. What people type into Google’s search bar, gives us an idea of what information they need, what is unclear and what questions need answering.

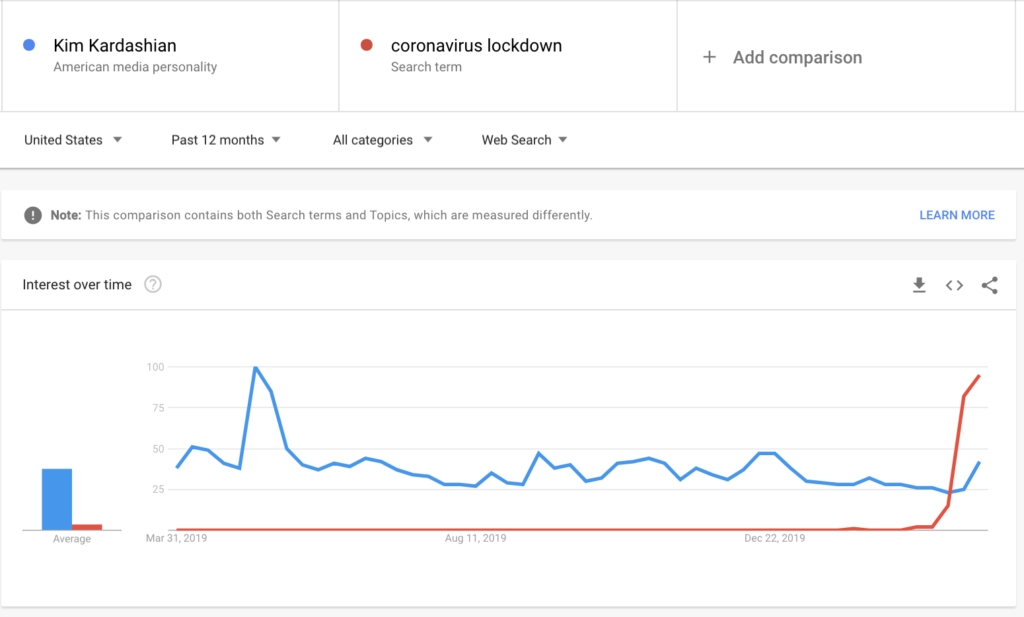

We recommend you do some comparison searches as that gives you a sense of interest. So, for example, compare Kim Kardashian with coronavirus lockdown. Here’s an image comparing these two search topics over the past 12 months in the US.

|

It’s also worth knowing that you can search by country, and when you do that it shows you search interest by region. Here is an image of Algerian search patterns comparing Kim Kardashian with ‘confinement’ (the French word for lockdown) over the past 7 days. You can see underneath the first graph a breakdown by region in the country.

Looking after your own emotional wellbeing

The coronavirus pandemic is anxiety-inducing for anyone, and reporters are no exception. Those who need to read about Covid-19 every day to keep the public informed may be feeling the brunt of information overload.

Reporting on the pandemic is a “one-two punch” of psychological pressure, said Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. The nature of the story itself is traumatic, with reporters interviewing survivor families, photographing victims and seeing distressing data, and it can have a direct impact personally. “That combination of factors is going to make the extended story of Covid-19 challenging for a lot of journalists.”

Studies suggest that the “resilient tribe” that is journalists are better than most at coping with trauma, said Shapiro. But even at the best of times, those in the industry are at risk of developing mental health issues.

So here we will set out seven tips for journalists reporting on the coronavirus outbreak, to help you look after your own mental and emotional wellbeing:

- Be aware of the stigma

- Separate work and life

- Stick to official guidance

- Check-in regularly with colleagues

- Create a self-care plan

- Know your triggers and ask for help

- Be kind to yourself

Be aware of the stigma

Vicarious trauma is common among journalists covering tragedies, and instances of post-traumatic stress are higher among journalists than the general population. Persistently high levels of stress corrode resilience and performance and can lead to burnout. But there remains a stigma around talking about mental health.

“[Journalism] lags behind other professional worlds in discussion of mental health issues”, said Philip Eil, a freelance journalist based in Providence, Rhode Island, who has written extensively about journalism and mental health.

Reporting requires bravery, but not bravado. Too often journalists pretend that they can take death and destruction in their stride. This has created a reluctance to discuss mental health and emotion in the industry.

“[Taking care of yourself] is about being a good journalist” – Philip Eil, freelance journalist and mental health advocate

“There’s so much about journalism itself that would take a healthy person and make them stressed, anxious or depressed,” said Eil, who has himself experienced anxiety, depression, and burnout through his work. “And that’s totally okay.”

He advises journalists that mental health issues are not illustrative of professional competence. “Know this work is likely to have an effect on you and be okay with that,” said Eil. “Don’t buy into the toxic and dangerous stigma that is pervasive in the world and profession.”

Separate work and life

Experts are advising people struggling with anxiety at this testing time to disconnect from the news. This can be almost impossible for journalists to do, but it is possible to draw a clearer line between work and home life.

“When you’re with your friends or family, have designated periods where work discussions are not allowed or during which you ban all discussion about the virus,” said Rachel Blundy, senior editor at AFP Fact Check based in Hong Kong. Her team has been at the forefront of fact-checking coronavirus misinformation but she has been trying to “continually discuss” with them how to avoid becoming drained by the coverage.

“I want everyone to feel like they can switch off when they are not at work” – Rachel Blundy, Senior Editor, AFP Fact Check

“Evenings and weekends are really our own,” she told First Draft. “We now only use Slack for work discussions, where previously we used WhatsApp. This has helped to create a clearer line between work and social time. I want everyone to feel like they can switch off when they are not at work.”

Limit the content you see outside of work hours. If you must have breaking news push alerts on your mobile device, choose just one outlet to receive them from, not a dozen.

Unsubscribe from newsletters that use alarmist subject lines or fill you with anxiety when they arrive in your inbox.

Eil believes disconnecting from work in your personal time to look after yourself is “part of being the best journalist you can be”.“Journalists want to stay up to date with their beat, but to be a top-flight journalist you have to take care of your mind and body, otherwise, it’s going to crash,” he told First Draft. “This is an investment in yourself as a journalist.”

Stick to official guidance

People already experiencing mental health problems are especially vulnerable during emergencies. For reporters already prone to anxiety, including health or contamination anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or work-related stress, the global focus on the virus is likely hitting hard.

From hand-washing to disinfecting surfaces and not touching your face, official guidelines can sound similar to OCD thoughts. It’s important to follow authoritative advice for protecting yourself and others from the virus, but also to know that it is not necessary to go above and beyond recommended practices.

Know the key facts without overthinking symptoms or precautions, Eil recommended.“You want to be prepared and vigilant, but you want to maintain sanity.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists has guidelines for reporters on the ground to keep themselves safe from coronavirus, which we would recommend reviewing.

Check-in regularly with colleagues

As more countries encourage social distancing, more newsrooms are adopting remote working. But this means journalists are more at risk of isolation while working harder than ever on a fast-paced story.

“Social isolation is one of the risk factors for physiological distress, and social connection and collegial support is one of the most important resilience factors,” Shapiro told First Draft, citing research into journalists covering trauma.