An examination of the social media landscape of the Chinese diaspora in Australia — the largest in Oceania — provides a useful case study for policymakers ahead of the next federal election. Findings aim to inform solutions to support and seek support from Chinese diaspora communities.

Introduction

Multilingual information and unfamiliarity with patterns of activity in the diaspora create risks of misunderstanding, misinterpretation and stereotyping. Most importantly, these communities are left vulnerable to mis- and disinformation campaigns.

This report highlights the complexities of how information is consumed and disseminated in the Chinese diaspora; how its multilingual mode of communication could make it a target of overt or covert influence campaigns; and how China’s “image” problem in the media affects diaspora communities.

This report offers an overview of the platforms on which the Chinese diaspora exchanges information. It explains the challenges of monitoring mis- and disinformation on Chinese platforms and closed messaging apps, as well as the interplay with platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. Overt and covert influence efforts in Australia by Chinese state agents, and others such as the anti-Chinese Communist Party Himalaya movement, are outlined.

The landscapes

The geopolitical landscape

Australia is home to more than 1.2 million people of Chinese ancestry. On the other hand, China is Australia’s largest trading partner and Beijing’s politics and diplomatic approaches directly affect the stability of the Asia-Pacific region.

However, Australia-China relations hit their lowest ebb in decades as the pandemic struck in 2020. Tensions between the two countries had been simmering for some time: China considered the foreign interference laws Australia passed in 2018 an insult.

Since Australia called for an international investigation into the origins of the coronavirus in April 2020, China had accused Australia of mass espionage and racism against Asians, including the Chinese diaspora, and hit back with trade blocks in the form of “economic punishment” as well as warnings against traveling and studying in Australia. These sectors are particularly reliant on China — Tourism Australia’s 2019 statistics found that about 30 percent of total overseas student enrollments and 15 percent of short-term arrivals were from China. Caught in the tit-for-tat is the Chinese diaspora in Australia, including ethnic Chinese who were born and raised in the country or migrated there later in life.

As Australia and China’s relations deteriorated, those from the Chinese diaspora who enter the political arena are sometimes treated as “guilty by association” and frequently face speculation about possible ties to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). These allegations are often based on people’s involvement in local Chinese community groups set up by the CCP, which does not necessarily mean the individuals themselves are involved with the political party.

These accusations can lead to candidates dropping out over fear of harassment. At a Senate inquiry into issues facing diaspora communities last October, three Chinese Australians spoke about the difficulties the Chinese diaspora faces in being pulled both ways in a geopolitical power struggle, leading to reluctance to participate in public debate. A conservative senator subsequently asked them to “unequivocally condemn” the CCP — ironically further demonstrating the sort of “gotcha loyalty test” Chinese individuals are subjected to simply due to their ethnicity.

Do Senators have the right to ask Chinese Australians to condemn the Chinese Communist Party? #QandA pic.twitter.com/pPO0gi0xiG

— QandA (@QandA) November 9, 2020

One of the Chinese Australians questioned by Senator Eric Abetz discusses the incident at ABC Australia’s Q&A in November 2020

This came against a backdrop on the international stage, where in the US the FBI labeled the Chinese government’s “counterintelligence and economic espionage efforts” as well as policies and programs that seek to “influence lawmakers and public opinion to achieve politics that are more favorable to China” the “China threat.” This provides important context for what can fuel online misinformation and disinformation as well as what to expect with propaganda.

The challenges — by design

Flying under the radar

A 2019 study stated that Chinese-language social media platforms such as WeChat and Weibo are perhaps “more powerful than traditional ethnic print media in explaining and promoting positions and opinions expressed by Chinese media consumers on a wide range of issues” due to their ability to reach a large database of users and the fluid nature of the space.

Instant messaging aside, WeChat has its own built-in “Moments” communications feature and payment services similar to those of Facebook, Instagram and PayPal.

Moments, or “Friend Circles” in Chinese, is the WeChat equivalent of Facebook and Instagram Feeds and is only for users with permission to join and generally unsearchable.

Express yourself with WeChat Moments. ☺️#WeChat #WeChatTurnsTen pic.twitter.com/hctAYpyvOs

— WeChat (@WeChatApp) January 28, 2021

A tutorial on Moments published on WeChat’s Twitter account

The Facebook-like Chinese-language microblogging site Weibo is perhaps less popular among Chinese people in Australia because WeChat offers similar features and more.

Semi-closed and censored

There are two key challenges to countries with a significant Chinese-language social media base. First, the closed, semi-closed and censored nature of these apps means misinformation, disinformation and propaganda might fly under the radar while quietly shaping users’ beliefs and attitudes. Second, regulation of the quality and accuracy of information in these spaces is lacking. However, abundant censorship from China is the norm. Toronto-based online watchdog Citizen Lab monitored the availability of coronavirus information on WeChat and YY (a livestreaming platform) at the start of the pandemic. It found the scope of censorship “may restrict vital communication related to disease information and prevention.”

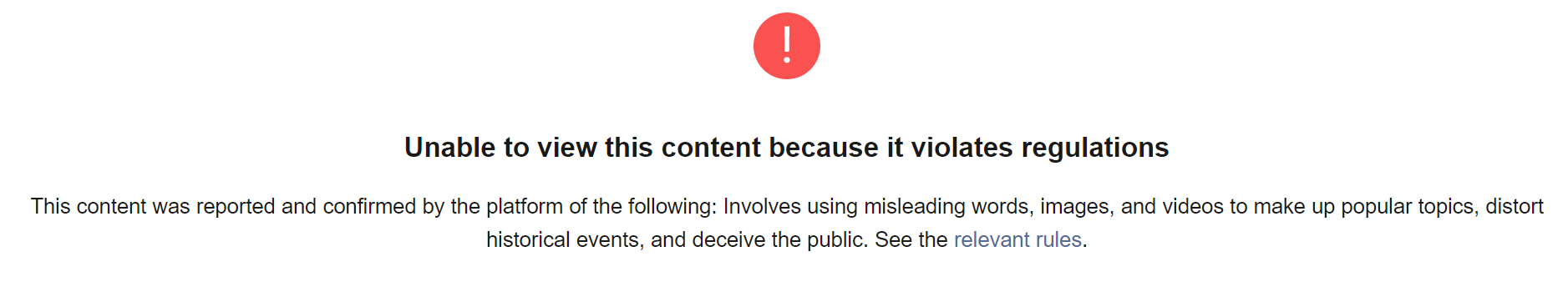

Censorship practices seemingly apply to everyone over matters considered a threat to the authority of the Chinese government and the peace and stability of China. Even Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison was not exempt. Morrison uses WeChat to connect with Chinese speakers, such as during Chinese New Year and the Mid-Autumn Festival. Last year, he attempted to soothe the country’s Chinese population when the two nations traded barbs after grim findings of Australian war crimes in Afghanistan were released. But WeChat removed Morrison’s post a day after it was published. The platform said Morrison’s article “violates regulations” and “involves using misleading words, images, and videos to make up popular topics, distort historical events, and deceive the public.” Another way WeChat monitors and censors its users is to block messages containing blacklisted keywords without notifying the sender or receiver.

A screenshot of the now-removed article published on Scott Morrison’s WeChat account; archived here

Prior and post-publication censorship

As it did with Morrison’s post, WeChat removes individual posts it deems violations of its terms of service or acceptable use policy. The platform does not appear to have any policies in place specifically addressing mis- or disinformation. However, prohibited activities listed under its acceptable use policy, such as impersonation and fraudulent, harmful, or deceptive activities, can cover some aspects of information disorder.

On the other hand, its content censorship is more political and arbitrary, and done in real time through keywords and keyword combinations. Citizen Lab’s research shows that such censorship occurs so the post or message is removed prior to publishing or sending, while violations of platform policy result in a takedown after publication.

Undermining the diversity of political discussions — ramifications for Australia

In Australia, these issues have both political and social ramifications. During the last election in 2019, a Chinese candidate was linked to the promotion of “scare campaigns” about an opposing party on closed messaging apps, including WeChat. Offline methods, such as placards that resembled official Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) signage written in Chinese instructing voters of the “right way to vote” for specific candidates, were subject to scrutiny (although this particular case was ultimately dismissed by the AEC). However, the online methods were unaddressed (according to the AEC, no complaints were raised to the body about such “scare campaign” messages), showing how disinformation and propaganda can blur in closed spaces and be overlooked as vehicles for political debate and civic participation. Given that Australia-China relations are at an all-time low, a lack of monitoring and research into closed and semi-closed platforms may run the risk of undermining the diversity of political discussions and missing out on the chance to mitigate security concerns.

Fact-check and monitoring limitations

The opaqueness of WeChat’s private Moments makes it virtually impossible to monitor the flow of mis- and disinformation there. Misinformation seems to primarily circulate in closed chat groups on the platform. Young Chinese Australians reported a large number of unproven claims about Covid-19, the vaccines and health in general circulating on WeChat. But there are currently only a handful of WeChat-based Chinese-language fact checkers who are able to verify information, such as 反海外谣言中心 (Centre Against Overseas Rumours) and 反吃瓜联盟 (No Melon Group) — the former consists of a team of 21 people (according to an introductory message the account sends to new followers), compared with the app’s over 1.2 billion users worldwide.

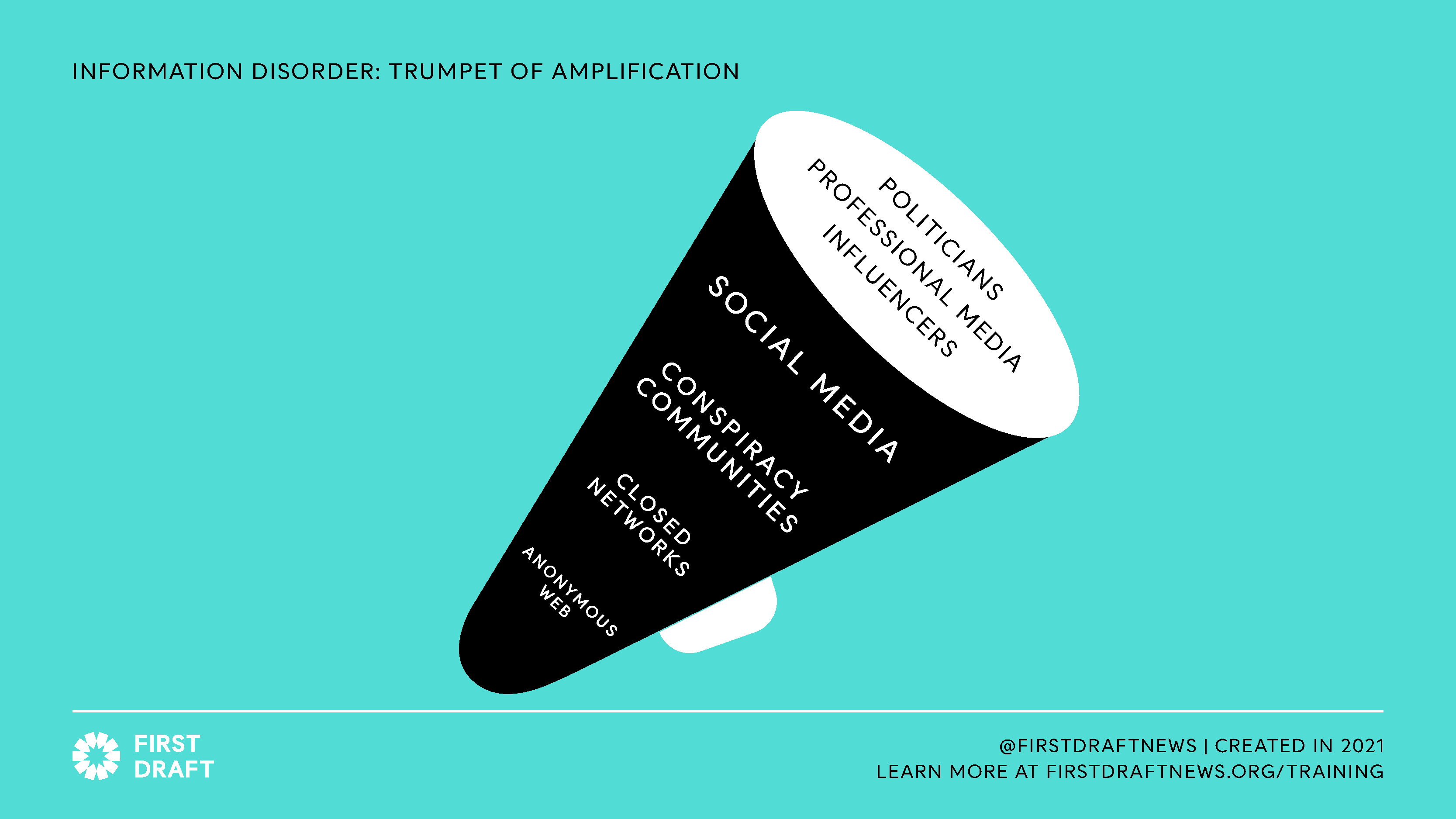

Have warning labels, won’t travel

Another problem lies in the warning labels fact checkers apply to problematic content on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Crucially, the labels applied to misinformation in ‘open’ spaces such as Twitter and Facebook do not travel with the false or misleading posts when they are shared on other platforms. Rather, inaccurate information circulates unchecked across the diaspora once it leaves the platforms where the contextual warnings were applied.

Search constraints and unlimited forwarding pose issues

Other features unique to WeChat act as roadblocks to researchers and policymakers who want to monitor mis- and disinformation within the app. There are no forwarding limits on WeChat messages, as there are on WhatsApp, to curb the spread of misinformation. There is a limit on the number of people to whom WeChat users can broadcast messages — a maximum of 200 people at a time — but no limit to the number of broadcasts one can conduct. Theoretically, a message can be shared unlimited times among the app’s more than 1.2 billion active users. There are no measures in place to stop its travel, unless it violates WeChat’s terms of service or acceptable use policy. The no-holds-barred approach can cause real-world harm prompted by a WeChat message that contains false, harmful information.

WeChat’s search bar only allows simple keyword searches and lacks an advanced-search capability, such as that on Weibo. Searches often return results about the most-read articles, not relevant users, and certainly not any content within private messages or in Moments.

The simplistic search function also presents a hurdle for meaningful analysis of misinformation, because it’s difficult to collect a large enough dataset to derive any sort of conclusion on how a misleading claim is broadly shaping the opinions of a user group.

Adding to the challenge is that unlike Facebook, which offers social media analytics tool CrowdTangle to view public content engagement insights, there aren’t monitoring tools conducive to the gathering of data from messaging apps like WeChat, partly because of privacy concerns.

Overt/covert influence — a closer look

First Draft’s research shows that robust and persistent attempts to influence ethnic Chinese in Australia are notable from both Chinese state actors and organizations against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Many of these attempts have used social media to promote narratives that serve their causes, whether to encourage loyalty to the CCP, or to galvanize activism and diplomatic changes against the CCP.

State media

A July 2021 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) found that anti-Asian violence amid the Covid-19 pandemic saw “Chinese diaspora communities continue to be an ‘essential target’ of Chinese-state-linked social media manipulation.” This followed a 2020 report by ASPI on a “large-scale influence campaign linked to Chinese state actors” targeting Chinese-speaking people outside China in an attempt to sway online debate, particularly surrounding the 2019 Hong Kong protests and the pandemic.

First Draft research found that on a more nuanced level, Chinese state actors have been trying to shape the debate about the spiraling Chinese-Australian relations. This includes broad issues (political stance and trade practices) as well as the personal (focusing on how the Chinese diaspora should be worried). Among the narratives are that the diaspora may not be safe in Australia in the face of “a wave of rising racism,” that Australia is becoming less popular in China, and that as the Chinese state-owned Global Times reported, “It’s wishful thinking in Australia that the bilateral relationship won’t affect the economic exchange and services trade.”

Research also found evidence of more covert efforts to push anti-Australian political rhetoric. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian, who has a million followers on Twitter, took a swipe at Australia’s report into war crimes committed by its Defence Force during the 2005-2016 war in Afghanistan alongside a provocative image that angered the Morrison administration and the general public. An analysis on some 10,000 replies to Zhao’s tweet by Queensland University of Technology lecturer Timothy Graham showed “recently created accounts are flooding the zone by replying to @zlj517’s tweet” and that a majority of these accounts state they are located in China, indicating possible bot activity and/or a coordinated campaign.

The Chinese propaganda machine doled out insults against Australia. On Twitter, Hu Xijin, the editor of Global Times, called Australia the “urban-rural fringe” of Western civilization, and said that the killings of Afghan civilians prove Canberra’s “barbarism.” The minister of the Chinese Embassy to Australia, Wang Ximing, reportedly attacked Australia’s “constitutional fragility” and “intellectual vulnerability” while at the same time calling for “respect, goodwill, fairness” in a speech about the China-Australia relationship. Once again, the Chinese diaspora bore the brunt of the war of words.

A collage of screenshots showing tweets from spokespersons for the Chinese government and state media targeting Australia

Anti-CCP

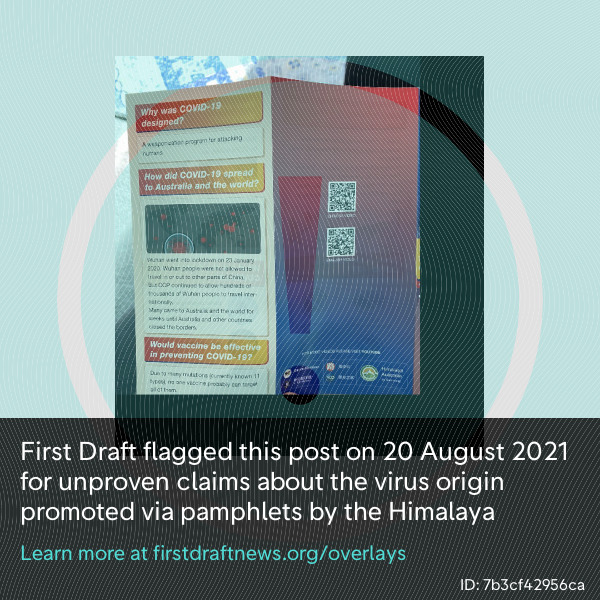

On the other side of the coin are groups that strive to promote anti-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ideologies. One of those groups is the Himalaya movement (喜馬拉雅), an anti-CCP group founded by exiled Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui and co-led by Guo and former Donald Trump adviser Steve Bannon. It recruits the Chinese diaspora, including in Australia.

Originally named the New Federal State of China (新中國聯邦) and sometimes also known as the Whistleblower movement, the group has been expanding throughout Asia-Pacific, North America and most recently Europe via “farms” around the world (“farms” being an allusion to their ideal paradise life). It has shared anti-CCP, anti-Joe Biden and US election fraud narratives, as well as coronavirus conspiracies, organized on Discord, Twitter and YouTube.

The group also has a dedicated website called Gnews, a video platform called Gtv, and the newly launched Twitter-like Gettr. Launched in early July by a former Trump spokesperson, Gettr claims to promote freedom of speech with no censorship, thereby quickly attracting conspiracy theories and hate speech. It is reportedly financially backed by Guo. Gettr’s predecessor, Getter, was a platform used by Guo to communicate with his followers, and there are signs that the ties between the new platform and the movement run deeper than funding.

Members of the Himalaya movement have made coordinated efforts to populate the website and use it to promote pro-Trump and anti-CCP narratives, including the idea that the coronavirus is a bioweapon created by China. These unproven or misleading narratives have been shared online and offline, via pamphlets, flyers and posters. First Draft’s research found the movement also has its own group of translators working to share promotional materials in multiple languages and has organized protests and rallies around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Italy.

A screenshot of an image showing a pamphlet distributed by Himalaya Australia

One “celebrity” in the group is Chinese virologist Dr. Yan Li-meng, who came under the umbrella of the movement in mid-2020 after fleeing to the United States. She became one of the strongest proponents for the movement after promoting the claim that the novel coronavirus is a bioweapon created in a Chinese lab. She used her previous employment as a virologist in China as evidence of her credibility, despite her last workplace, the University of Hong Kong, distancing itself from her, and other institutions discrediting her work as baseless. Through these credentials and the movement’s ties with high-profile figures in the US, Yan has garnered over 112,000 followers on Twitter after numerous appearances and interviews with outlets such as Fox News, Newsmax and the Daily Mail.

In the run-up to the 2020 US presidential election, First Draft saw some crossover between Himalaya and QAnon-supporting accounts, with the mutual goal of seeing Trump re-elected. The movement also has ties with former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, who was at the forefront of the Hunter Biden hard drive scandal. First Draft discovered that rumors about the hard drive were first mentioned online by Himalaya pundit Wang Dinggang, also known as Lu De, in a September 2020 YouTube video. The video was uploaded weeks before the New York Post’s “smoking gun” article was published, and QAnon-supporting Twitter accounts retweeted Himalaya’s hard drive claims as evidence that Joe Biden should not be elected. Some Himalaya supporters have also promoted QAnon claims about the “Deep State,” which they spun as having a mutually beneficial relationship with the CCP.

Members of the movement pay close attention to press coverage and sometimes issue strong rebuttals. For instance, ABC Australia journalist Echo Hui, who is ethnically Chinese, was called out in an “open response” to her email inquiry to the group’s Australia branch (despite the fact that she was not the only journalist who had worked on that story). Himalaya followers also marched to the public broadcaster’s Brisbane office following its report on the movement. The group accused ABC Australia for having been “weaponized to spread leftist ideology” and “producing fake news against the New Federal State of China.”

On the other hand, when The New York Times published its feature on the movement, Lu De covered it in his livestream show, saying he was happy that the movement had made it to the pages of the Times, as this meant the movement and its ideology had become mainstream (“承认了这个成为了主流思潮了”).

The Himalaya movement has an interest in spreading its ideology and theories to the mainstream media. The Hunter Biden hard drive scandal was not the first time Himalaya surfaced something that later made it into the broader public sphere. It was first to post online about a discredited Chinese document published in 2015 containing conspiracy theories about the use of coronaviruses as bioweapons. The movement initially publicized the existence of the book in February 2021, claiming it as proof that Covid-19 is a CCP bioweapon. By May, national newspaper The Australian echoed the possibility of the claim in an exposé-style article about the “chilling” document.

News outlets should be wary of possible amplification and consider how much traction Himalaya disinformation is getting before introducing the movement to a wider audience. While publication may not always be necessary, research on groups such as Himalaya is essential because they operate on a member system and organize in semi-closed spaces. A lack of insight to the kinds of narratives they are pushing among the Chinese-speaking population in Australia could pose ideological and security risks.

The Trumpet of Amplification: How content moves from the anonymous web to the major social media platforms and the professional media. Source: First Draft

Guiding solutions for policymakers

Policymakers who wish to engage with the Chinese diaspora should hire Chinese speakers who are familiar with popular social media platforms and messaging apps such as WeChat, Weibo and Australia Today (an all-in-one app where users can access news, classified ads, a Quora-style Q&A board and a dating/matchmaking service). With the necessary language skills and Chinese social media know-how, they can help formulate strategies and social media campaigns tailored to the needs of the communities and protect them from malinformation.

A substantial amount of relevant data about the Chinese diaspora is needed for an outreach program to be effective. This can be achieved by setting up online monitoring systems to facilitate social listening, using free tools such as Google Alerts or CrowdTangle’s Link Checker.

For those who are unfamiliar with information disorder and social analytics, these practices may seem daunting and hard to execute. However, policymakers can actively seek the opinions and expertise of industry experts who are well-versed in the Australian and Chinese diasporic social media landscape. Tapping into research by disinformation experts, setting up a tip line for reports of election-related mis- and disinformation and funding surveys or projects to gain insights into particular issues are all ways to achieve a clearer picture of these communities’ social media habits. Content insights about the types of information they choose to share — and more importantly, the relationship between their online interactions and real-life actions, including their voting decisions — are invaluable.

High-level roundtables with disinformation experts, officials from defense and foreign affairs and social media companies can bring stakeholders together for a better understanding of the risks mis- and disinformation pose. Crucially, policymakers must grasp the fact that online discussions based on false information, half-truths and conspiracy theories can snowball into a serious problem, even a national security threat — the January 6 US Capitol insurrection is a textbook example.

Closing remarks

The Chinese diaspora’s ancestry and language skills make it a possible target of exploitation, but these are exactly the areas that can be turned into invaluable assets for authorities who wish to embrace the increasingly diverse population in Australia. The Chinese regime does not represent all people of Chinese origin, so a more appropriate approach is to stop vilifying people based on their race or ethnicity — starting with the media. Social media platforms should continue to tighten enforcement of their hate speech rules to reduce online discrimination.

As our analysis shows that language skills alone might not be enough to get a sense of how misinformation flows through the Chinese diaspora, an acute understanding and active monitoring of where, when and how they converge online is crucial.

Instead of leaving misunderstandings unaddressed and allowing racist stigma to run deeper and become more dangerous, policymakers and information providers should seek to understand, support and engage the Chinese diaspora o formulate more effective policies both for them and for the rest of Australia.

Anne Kruger contributed to this report.

This research was conducted with support from Facebook Australia.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.