On February 8, Facebook announced a harder line against Covid-19 and vaccine disinformation, outlining a range of specific, patently false statements about Covid-19 and vaccines that it would remove. We had a question: Were posts containing the claims still spreading? If so, how many were there, and what kind of reach did they have?

Our investigation focused exclusively on unfounded Covid-19 vaccine claims, such as that the vaccines change people’s DNA. Using data exported from Facebook’s insights tool, CrowdTangle, we found at least 3,200 posts, attracting 142,049 likes, shares and comments, that had been posted on the platform after the ban.

From seed to story, it took around a month before we published these and other findings with WIRED UK. Here are some of the ethical and technical challenges we had to consider and how we addressed them, followed by a step-by-step methodology.

Ethics challenges

Analyzing vaccine mis- and disinformation is an ethical minefield, particularly as many Facebook posts are from vaccine-hesitant communities unknowingly spreading false claims about the shot (misinformation), as opposed to intentionally spreading rumors about it (disinformation). For the data investigation, we focused exclusively on outright false claims that Facebook itself had banned.

It’s important to consider how a platform was developed and the challenges it faces when reporting on platform action. For this reason, we considered how platforms are attempting to tackle misinformation, particularly as they routinely update policies. This is why we assessed claims Facebook had outlined — to be able to directly scrutinize action Facebook has already pledged to take.

Technical challenges

Researching a numerical evaluation of mis- and disinformation is challenging because it’s difficult to assign intent. Focusing on keywords retrieves all posts containing your specific search, leading to false positives. For example, it is possible to capture all posts that include a certain keyword or hashtag, such as “Bill Gates,” but the query will retrieve a number of different examples. Some of the posts including that term could easily be a debunk about a false Gates claim, someone asking a genuine question about the philanthropist’s relationship to the pharmaceutical industry, or a “bad actor” deliberately asking a question about Gates’ relationship with a pharmaceutical company as a way to sow doubt. These issues mean it is practically impossible to assess the full scale of misinformation on social platforms using keywords and hashtags.

In addition, the data accessible through Facebook and other platforms’ public API — Application Programming Interface, basically what allows exchange of data between platforms and users — is inconstant and inconsistent. Its ephemeral nature makes it hard to say anything conclusive. The keywords only reach a fragment of the online conversations’ real scale and don’t capture the complexity of speech used in online communities.

There are also external variables that can compromise the reliability of the analysis. News events might boost the numbers — for example, the announcement of a country suspending a vaccine, which is what happened in several European countries with the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine. Recurring events and holidays also affect the trends, which is why it’s more accurate to compare data on an annual or seasonal scale.

Conscious of these limitations, we developed a methodology that addressed these challenges while still providing meaningful analysis. In this way, while the numbers are far from conclusive, they are still able to demonstrate that a significant number of outright false claims reached large audiences before being taken down.

How we did it

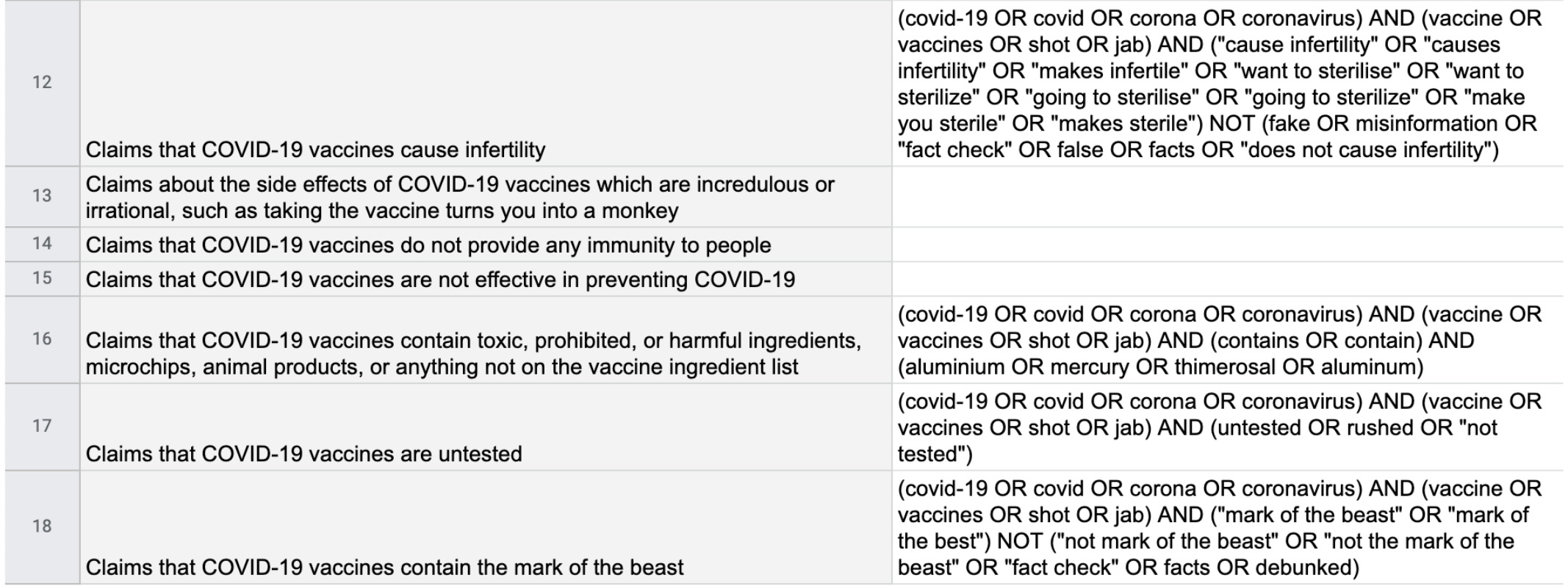

First, we compiled a list of Facebook’s newly banned claims related to Covid-19 vaccines in a spreadsheet. For each claim, we compiled relevant keywords, testing different combinations on CrowdTangle and selecting those that were most likely to retrieve disinformation. We translated the keywords into French and Spanish using a Google spreadsheet trick — by typing on a blank cell: =GOOGLETRANSLATE(cell with text, “source language”, “target language”). We then wrote Boolean search strings that would find users making the claims on Facebook.

The false Covid-19 vaccine claims outlined by Facebook and equivalent Boolean search queries. Screenshot by Lydia Morrish

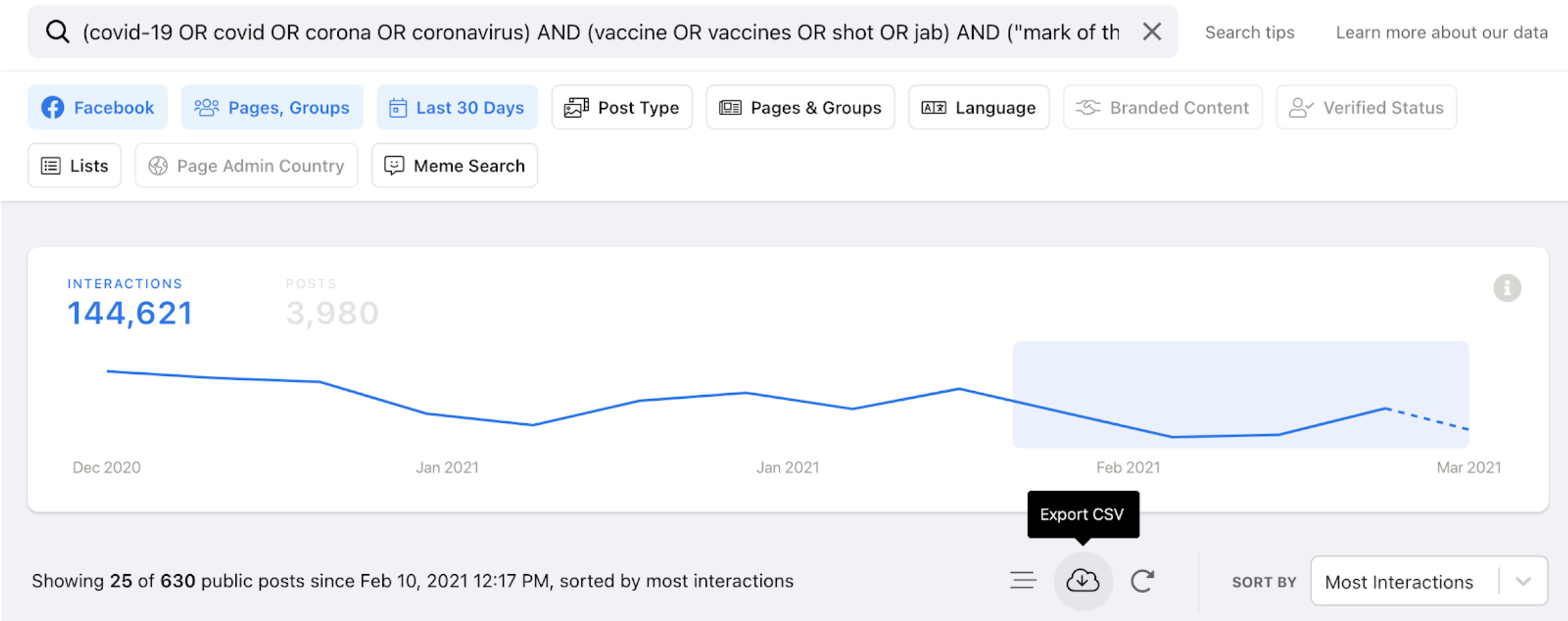

This data retrieval can be done through CrowdTangle’s historical data function or using CrowdTangle’s search tool, available to CrowdTangle users. Simply enter your search string and hit “export CSV” to retrieve data on posts containing the search terms (see First Draft’s step-by-step guide from last year for more on that). We also attempted to export Instagram data but didn’t receive many results, so we excluded it from the analysis.

CrowdTangle’s search tool. Screenshot by Lydia Morrish

Most searches retrieved thousands of results containing not only the prohibited claims, but also a lot of false positives. Checking our entire collection of tens of thousands of posts for disinformation would have been a resourcing nightmare.

Instead, we focused on the top interacted-with posts. Using the pivot table function on Google Sheets, we grouped individual posts by number of appearances and interactions. We then manually checked the content of the most interacted-with posts and tagged those posts containing explicit references to the false claims listed by Facebook as those the platform would take action around.

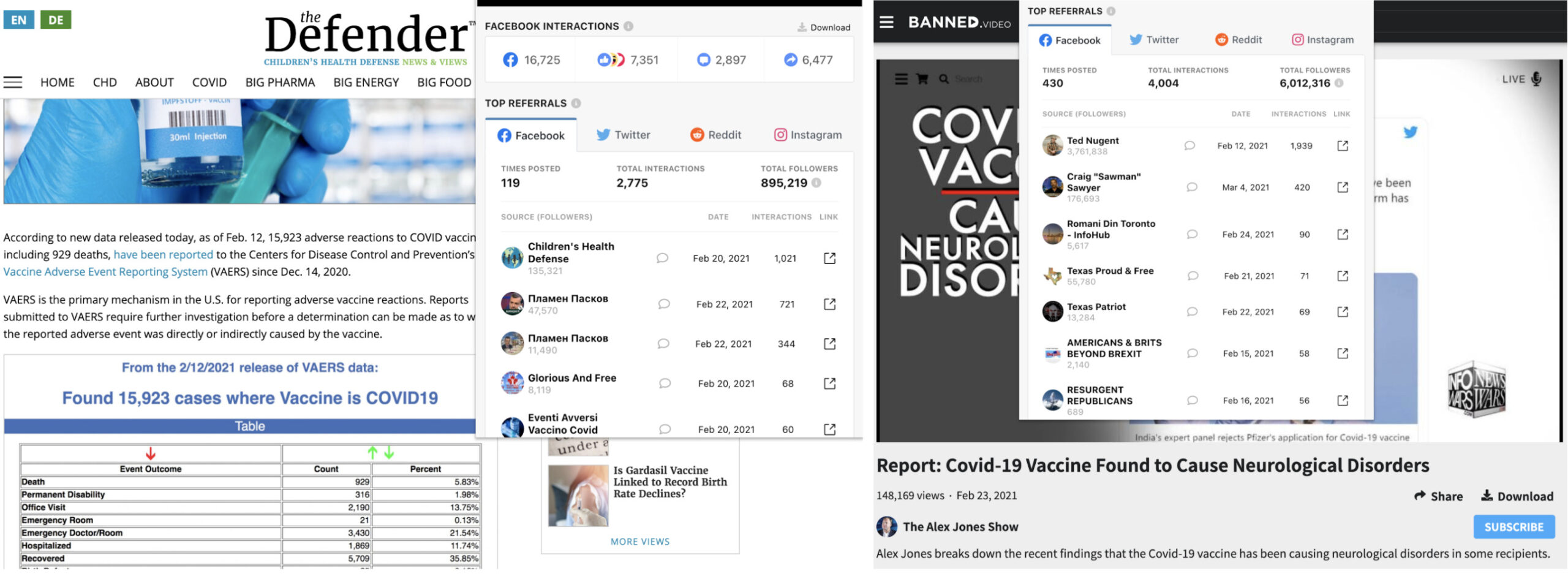

We also focused on posts sharing dubious articles and videos that were published on conspiracy theory websites such as BitChute and BanThis. Using CrowdTangle’s Link Checker Chrome Extension, we downloaded data on these conspiracy theory Facebook Groups and Pages sharing the link after February 8.

CrowdTangle’s Link Checker tool shows social media shares of some misleading links. Screenshots by Carlotta Dotto

Once again, the limitations of our approach are numerous and it is impossible to calculate the full scale of misinformation on Facebook. The data tagged and collected based on link-sharing activity in particular is likely to be only a small part of a much bigger picture.

But thanks to these collection methods, we were able to calculate the volume of posts containing the false claims, quantify how many likes, shares, comments and reactions they produced and analyze the most active Public Groups and Pages in the dataset.

And we can conclusively say there is still damaging Covid-19 vaccine misinformation on Facebook, despite the steps the platform has taken.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.

Correction: A previous version of this article said CrowdTangle Search was publicly available. CrowdTangle is only available to Facebook partner organizations and individual journalists who are registered with Facebook. A reference to “data scraping” has also been removed to clarify that the data was gathered using an export function that CrowdTangle provides.