By Mattha Busby, Isaan Khan and Eve Watling

After four weeks of systematically monitoring online conversations and content related to the UK election, we found that there was a serious problem with the sharing of misleading information during the campaign. Many politicians and journalists use data well to argue their point but there are examples of facts being distorted throughout the election. Unlike the US election, the most misleading content didn’t come from newly created websites or automated accounts created to push disinformation. Instead, misinformation in the UK election came from misleading headlines, graphics and statistics from the mainstream press, political parties and hyper-partisan websites.

Here we outline five different types of problematic content, and share key examples from each. While the purpose of this piece isn’t to name and shame, we do want to highlight the scale of the issue. Whatever you make of each individual example, when they are viewed together over four weeks, it presents a depressing reality that misinformation is being disseminated throughout online spaces. Just like social media users might be prone to retweet an infographic without meticulously checking every last figure; mainstream media outlets too are susceptible to misinformation.

1.) Misleading headlines in mainstream newspapers

We found numerous examples of mainstream publications publishing misleading stories.

One example was the misrepresentation of a Oxford University report used by the Telegraph, which caused the researchers to describe the article as ‘fake news’. The article focused on 21,000 automated tweets that consistently supported Labour, using the headline: Labour election campaign boosted by bots’. The article acknowledged that 13,000 tweets were also discovered supporting the Conservative Party, but this was only mentioned in the latter part of the article. Using a headline focused solely on Labour framed the story in absolute certainty that automated posts boosted the party’s position in the election. In an era where so many people see only headlines and visuals via Facebook or Twitter feeds, headline choice has an even greater impact on readers.

In another example, The Daily Express unearthed an Ohio court case where a woman named Gina Miller was jailed after conning her clients to fund a lavish lifestyle. The body of the text confirmed that they were not writing about Gina Miller, the lawyer and Brexit campaigner, but as in the previous example, for anyone scrolling through social media without clicking on the story (as many of those sharing clearly did not), the headline is likely to have been taken as talking about the Brexit campaigner: ‘Gina Miller jailed after conning clients out of £800,000 to fund lavish life’.

2.) Exaggeration and misinformation by the hyper-partisan press

We were featured in The Guardian debunking this story and revealing the site’s links to the satirical website Southend News Network

The rise of hyper-partisan websites – which only publish complimentary stories about their preferred parties and mix opinion into their reporting – and their related social media accounts was a striking pattern during this election. The content created by these sites sometimes received much more traction than content created by national newspapers online, when we compared interactions on the social monitoring platform NewsWhip.

These sites were much more likely to exaggerate and to appeal to existing biases. As BuzzFeed News reporter Craig Silverman showed, during the US election hyper-partisan sites published false and misleading content at alarming rates, becoming experts at using Facebook to drive traffic, employing emotional headlines, images and captions to encourage sharing without reading.

In the UK, one of these sites was Evolve Politics, which exaggerated the Conservative Party’s commitment to lifting the ban on ivory sales. It claimed in a headline that ‘Theresa May’s Tory manifesto scraps the ban on elephant ivory sales after bowing to millionaire antique lobbyists’. Had they given the Conservatives a right to reply to the article, they would have found out the government’s policy remains as outlined in September 2016, and they were still committed to the ban on post-1947 ivory sales. Between April 17-May 31, the ivory article was the 9th most shared article about the UK election on Facebook, with 42,500 shares.

In another example, the site YourBrexit.co.uk focused on the so-called Brexit divorce bill that alleged that Jeremy Corbyn had agreed to pay the bill in full without any factual basis. Another article was a purported leaked plan by Jeremy Corbyn to ‘allow thousands of unskilled workers into the UK after Brexit’ and was posted by the right-leaning blog Westmonster, for which we couldn’t find any evidence, and according to the Telegraph, similar proposals were reportedly under consideration by the Conservative Party as well.

3) Hyper-partisan websites attacking the mainstream media

In addition to publishing misinformation, many hyper-partisan websites accused mainstream news sources of heavy bias, misleading reporting and outright fabrication.

A Canary article announced Manchester had banned The Sun in the wake of the Manchester attack, ‘after its appalling response to the concert bombing’. They wrongly claimed that The Sun’s ‘BLOOD ON HIS HANDS’ headline was an attack on Corbyn in relation to the attack, when it in fact referred to his supposed friendship with Gerry Adams. Moreover, The Sun had released its first edition before the attack had even happened. The Canary soon took down the article, but did not issue an apology.

On another occasion, a hyper-partisan website wrongly accused Sky News anchor Faisal Islam of alleged off-camera musings that the Manchester terror attacks could benefit Theresa May. First Draft debunked that claim and concluded that Islam did not make those comments, although he was privy to the conversation in which they were made. The article has not been amended.

Hyper-partisan allegations of mainstream news organisation bias were a constant trend throughout the campaign. CNN was accused of ‘fake news’ for allegedly staging anti-terror Muslim demonstrators. Avideo was posted multiple times on Twitter and Facebook: the footage was originally filmed by Twitter user @markantro. His tweet of the video received 17k retweets and 20k likes. However, Snopes factchecked the claim and found it to be false. CNN also issued a statement denouncing the claims as “nonsense”.

4) Official political party pages bending the facts

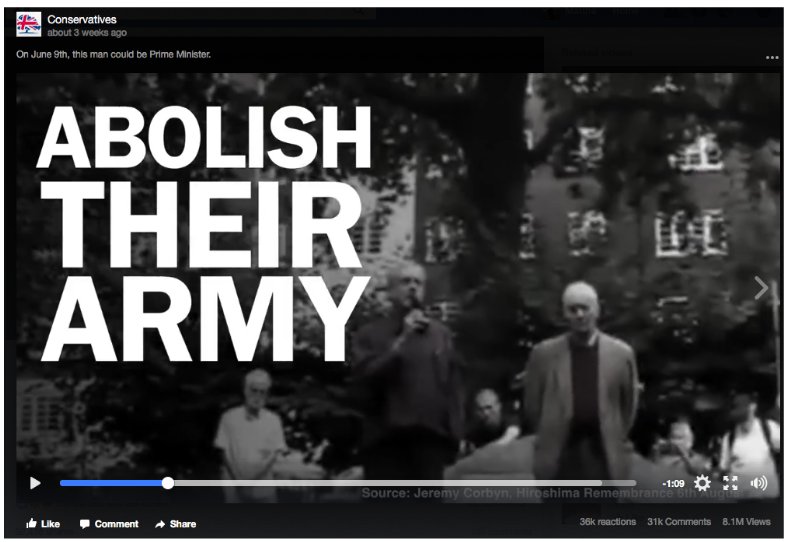

Corbyn’s comments about the Costa Rican army were reduced to a three word quote.

Political parties also used misleading information on their official social media accounts.

The attack advert on Corbyn by the Conservative Party, which spliced together a variety of speeches into seconds-long soundbites, suggests that he did not condemn bombings by the IRA and that he also called for the abolition of the army. In fact, he condemned all bombing – including that of the IRA – while his “abolish the army” quote was taken out of context. The video has had more than 7 million views.

Meanwhile, a Labour Party video attacked May’s record on police cuts. In the video, the Labour Party claimed there were 4,650 police job cuts by 2011; 9,655 job cuts by 2012; 17,125 by 2015; and 20,000 by 2017. Official government data substantiates these claims. The video is confusing, however, given that at no point do they declare that the figures are cumulative. This could leave one to believe that there were 17,125 police officers cut in 2015 alone.

5) False rumours that got traction before being flagged as false by us or others

We occasionally saw rumours beginning to spread on social media and then being taken up by online influencers once they started to gain momentum. These types of rumours were also often spread even further by hyper-partisan websites and did very well with their target audiences.

One example was a Facebook post that claimed a Devon hospital maternity ward and A&E department were closing, and that staff must not disclose the news until after the election. In that particular scenario, a quick check with an official source, Councillor Ian Williams of Yeo Valley Ward in Barnstaple, allowed us to debunk the story.

We found that viral stories were often related to institutions or politicians and included some kind of “extraordinary” angle or quality. A tweet published by an anonymous Twitter user showed the ‘transcript’ of a letter sent by a Conservative peer resigning from the party to join the Liberal Democrats. The story was picked up by the Guido Fawkes blog with little additional information, before we debunked it in one of our emails to our newsrooms partners.

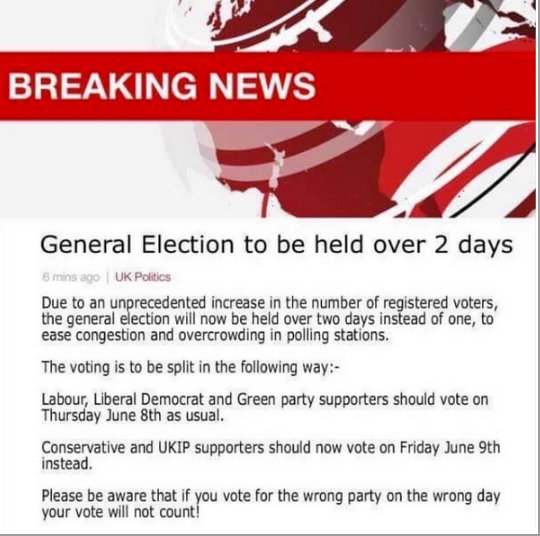

Another case was the altered screengrab headed by the BBC ‘Breaking News’ logo, which circulated on Facebook, claiming that “due to an unprecedented increase in the number of registered voters”, the election would be spread over two days. The image originated from a site where people were uploading spoof Tory election campaign posters and memes.

An altered screengrab attempted to encourage Conservative and UKIP supporters to vote on Friday June 9, after polls would have closed.

Conclusion

The misleading use of headlines, images and statistics has always been an element of a partisan press. Although many politicians and journalists use facts and statistics well to make their case, there are also many examples of facts being stretched to or beyond the breaking point. But what was noticeably different during this election, was the rise of the hyper-partisan blogs and their Facebook pages, which were highly effective at spreading false and misleading information. They sometimes got thousands of shares, competing with content from the mainstream media. While there was no sudden influx of websites specifically devoted to spreading disinformation throughout the campaign, many false stories were published the hyper-partisan press from unfounded social media posts.

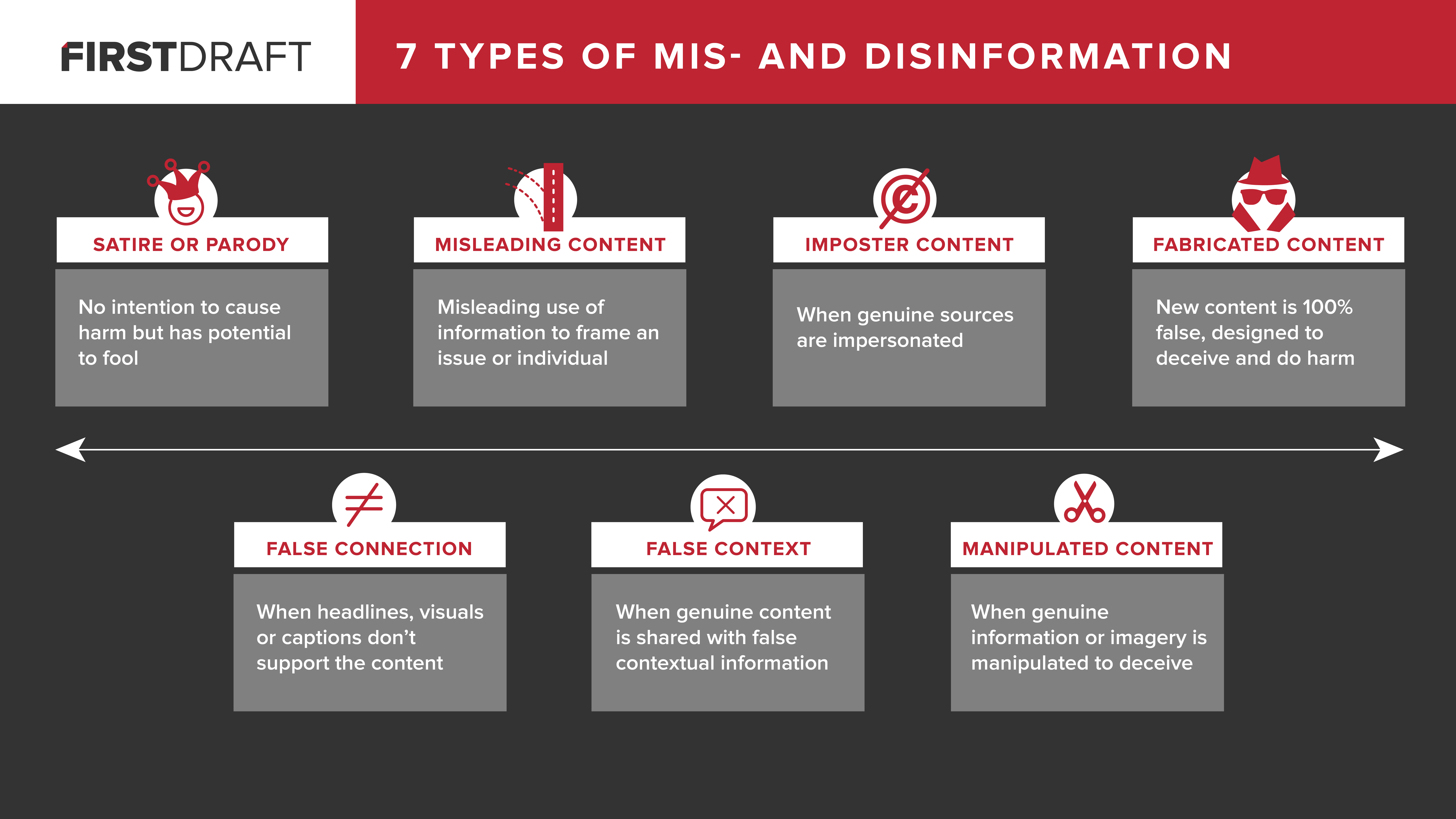

In First Draft’s typology of 7 types of mis- and disinformation, misleading content is one of the points on the spectrum, being described as ‘misleading information used to frame an issue or individual’.

Some might argue that this is nothing new and shouldn’t feature as a type of misinformation, but we believe this type of content – whether it’s shared by hyper-partisan sites, the mainstream media, politicians or parties – is playing a detrimental role in terms of trust. While money comes to fund news literacy projects, it’s important that the focus isn’t just on teaching people how to spot 100% ‘fabricated content’, but also on teaching people about the power and potential impact of headlines, visuals and captions to frame stories in misleading ways.

——

We are a team of nonpartisan journalists working with Full Fact and First Draft, brought together to monitor online conversations and investigate misinformation circulating in the UK general election.

During the campaign, we amassed more than 2 million tweets and 50,000 Facebook posts from political groups, pages and individuals with large potential audiences. With this data, we were following popular and trending topics with an aim to predict tomorrow’s stories.

Our tools included NewsWhip, Trendolizer and CrowdTangle, which allowed us to scan conversations on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, Instagram and YouTube.

We sent twice-daily newsletters to newsroom subscribers during the campaign.

Facebook and Google News Lab supported First Draft and Full Fact to work with major newsrooms to address rumours and misinformation spreading online during the UK general election.

This is the third in a series of blog posts about the Full Fact-First Draft UK Election project.

1. UK election first post: what we learned working with Full Fact

2. How we fact-checked the UK Election in real time