Australian election misinformation playbook

The challenge of monitoring, understanding, defining and responding to mis- and disinformation is exacerbated during election campaigns. This report outlines tactics used by agents of disinformation to undermine elections as observed by First Draft’s global monitoring since 2015. This is placed within a brief overview of the characteristics and vulnerabilities that bear consideration during elections in the Australian context. Campaign tactics have also furthered the spread of falsehoods and mis- and disinformation in Australia. This creates additional challenges (for which there are emerging solutions) when debunking political misperceptions that people may initially label as ‘misinformation’.

This report outlines why word choices matter. Consideration must be given ahead of an election to the level of understanding audiences and politicians alike have of definitions. Regardless of political leaning, they must be able to consider whether a claim that something is ‘misinformation’ could actually be political bias or misunderstanding of the definitions. As the Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation noted, concepts and definitions “mean different things to different people and can become politically charged when they are used by people to attack others who hold different opinions on value-laden political issues on which reasonable people may disagree.” The code also noted “understanding and effects of these concepts varies amongst individuals and is also under-researched.” First Draft recommends more research from an Australian perspective in this field.

The crucial role journalists play in countering political falsehoods and slowing down mis- and disinformation is explained. We encourage research, training and outreach that focus on this role and help prepare audiences for misinformation so they are better equipped to spot it and question it.This must be an ongoing pursuit, so that quality information is within easy reach of the public. This report also challenges politicians to consider their campaign responsibilities with regard to the role they may play in the spread of misleading information, and aims to help policy makers and legislators make informed decisions about supporting the information ecosystem.

Introduction

An election is an easy target (and opportunity) for the creation of misleading information. It can take many forms — memes, articles, audio messages, videos, screenshots and even comments on social media posts. Generally speaking, First Draft refers to misleading content as either misinformation or disinformation; the difference between the two is intent:

- Disinformation is when people deliberately spread false information to make money, influence politics or cause harm.

- Misinformation is when people do not realize they are sharing false information. It is important to understand that most people share misleading content out of genuine concern and desire to protect others.

In reality, it is rarely so neat. The lines between mis- and disinformation can blur, overlap and be repurposed. Often when disinformation is shared it turns into misinformation. Take, for example, false Covid-19 “remedies,” many of which have caused real-world harm. Conversely, something that starts as misinformation can be picked up by disinformation agents with an agenda. For example, a journalist misreporting the cause of an Australian bushfire season as an arson wave which is then picked up by conspiracy theorists with a climate denial agenda. A third category, called “malinformation,” exists when the information is true, but is shared maliciously, (e.g., leaked emails or revenge porn). First Draft co-founder Claire Wardle collectively referred to the different types and interplay of misleading content as information disorder.

Wardle noted that the “weaponization of context” — where genuine content has been warped and reframed — is a particularly effective tool for agents of disinformation and “far more successful in terms of persuading and engaging people.”

As noted above, definitions are complex and can mean different things to different people. First Draft has updated nuances and explanations as tactics in Information Disorder evolve. For example, socio-psychological factors are behind why people share misinformation, as has been particularly evident during the pandemic. As First Draft reported, online, people perform their identities. They want to feel connected to their ‘‘tribe,” be it members of the same political party, parents who don’t vaccinate their children, activists concerned about climate change, or those who are a certain religion, race or ethnic group.

The political ideology of an audience member can influence their perceptions of credibility and hence what they may consider to be ‘misinformation’. In what is known as the worldview backfire effect, a person rejects a correction because it is incompatible with their worldview, and can cause them to double-down on their views. If information is coming from a source they suspect disagrees with their beliefs, they may say it is ‘misinformation’ rather than realizing it is their opinion. Research suggests political ideology can also influence trust in the media. For example, in the case of anti-lockdown protests where much of the narrative was anti-government, mainstream media were also portrayed as untrustworthy for being the ‘source’ reporting on government messaging. In Australia, by May of 2020 protesters began to take their ‘offline’ disinformation comments into the real world in Melbourne. The seemingly disparate groups of anti-vaccination and anti-government contrarians adopted rhetoric from international conspiracy theories. This included false information about Bill Gates and the government trying to microchip citizens, as well as 5G mis – and disinformation and other health misinformation. These narratives continued as different protests evolved throughout the pandemic. More recently this worldview backfire effect was evident among the Convoy to Canberra protests.

Australian context and political salience

The events of 2019 and 2020 were a watershed moment where ordinary Australians gained a heightened awareness of mis- and disinformation in their own country. This included higher exposure to and engagement with various forms of mis- and disinformation during the coronavirus pandemic, the summer of bushfires and the 2019 federal election. Many examples from these events show Australia’s current and future vulnerabilities to mis- and disinformation.

These issues were quickly politicized in Australia. Those at risk of being targeted by agents of disinformation included government agencies, e.g., through fabricated social media pages that contained anti-Asian sentiment. Racist narratives from the pandemic added to the challenges for diaspora communities; these narratives sprang from a 2019 federal election that consisted of extreme right-wing, white nationalist online disinformation campaigns and hyperpartisan campaigns pushing anti-immigration agendas.

Meanwhile, Chinese communities were targeted by misleading campaign material in the form of signs that resembled those used by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), which supervises and organizes elections. The federal court found the signs, written in Chinese on how to vote, were misleading and deceptive. But the AEC also found there was “no real chance” the signs could have affected the results and ruled out referring the Liberal party’s former Victorian state director to the high court over his role in authorizing the signs. This was despite admissions that the signs were intended to look like the AEC’s material. Chinese communities was also targeted in “how to vote” scare campaigns in hidden chat rooms.

Australian politicians use negative campaigns and “attack ads” to target opposing candidates and policies. The 2019 vote also saw debunked information used as part of an online political scare campaign about inheritance tax. This “zombie rumour” about death taxes was repeated by mainstream politicians from the ruling Liberal party and hyperpartisan groups such as the nationalist party One Nation. They took a kernel of truth and adapted it for their purposes. Research by academics Andrea Carson, Andrew Gibbons and Justin B. Phillips used a content analysis of 100,000 media articles and 8 million Facebook posts to track the claim, and found “a number of actors circulating and co-opting the death tax story for political purposes.”

As First Draft reported at the time: Labor requested Facebook remove the posts, warning in a letter that there “seems to be an orchestrated message forwarding campaign about the issue.” Facebook Australia told First Draft that the original post was fact checked by third-party fact checkers and was rated as “False.” “Based on this rating, people who shared the post were notified. … As a result, the original post and thousands of similar posts received reduced distribution in News Feed,” a Facebook Australia spokesperson said.

The “death tax” claim tactics echoed Labor’s 2016 negative campaign, which included emotional television ads that suggested the Liberal-National Party coalition planned to privatize the nation’s public health care service, Medicare. Academic researchers Andrea Carson, Aaron J. Martin and Shaun Ratcliff found the so-called “Mediscare” campaign “significantly raised the issue salience of healthcare with voters, and it had an impact on vote choice, particularly in marginal electorates.” The researchers found the campaign slowed a decline in support for the Labor party “that was evident prior to the commencement of the negative campaign” and “this negative campaign was effective in shaping the 2016 electoral outcome,” which resulted in a narrow victory for the coalition, led by Malcolm Turnbull.

Sticking power and political persuasions

Research shows, perhaps unsurprisingly, that when it comes to fact checks on political content, people “take their cues from their preferred candidate” especially when the information challenges the political identity to which they feel they belong. That is not to say that fact checks don’t work; rather, the problem is in how they are delivered, and how regularly people stumble upon or are reminded of the fact-check content. As American political scientist Brendan Nyhan explained, “with the exception of a few high-profile controversies, people rarely receive ongoing exposure to fact checks or news reports that debunk false claims.”

As a solution, Nyhan suggests the communication style of scientists, journalists and educators should “minimize false claims and partisan and ideological cues in discussion of factual disputes” and instead highlight “corrective information that is hard for people to avoid or deny.” For example, “opinion” TV shows or columns that invite guests with alternative viewpoints for the sake of “balance,” such as climate denial, do not follow the proven science, and allow for a false equivalence in discussions.

Research has borne out the importance of getting reporting that fully explains context and events, rather than just “he said/she said,” in front of people. More continuous targeting with quality information is also essential. As Carson et al noted, “when journalists adjudicate claims (i.e., refute false claims within stories rather than simply providing competing “he said/she said” accounts) it can be beneficial to both the audience and media source.”

As noted below, a patchwork of laws and a laissez-faire approach to political advertising have resulted in a lack of accountability in political campaigns, and the spread of falsehoods, mis- and disinformation. The research above shows the need to include debunks throughout stories, as it sets challenges for journalists attempting to cover politics particularly stuck in the daily “horse race” and “he said/she said” reporting cycle.

The oldest, and newest, tricks in the election playbook

First Draft has covered elections around the world since 2015 — from France to the UK, EU, Brazil, Nigeria, US, New Zealand and Australia. From this, we have come across numerous election tropes and online election interference tracks. An awareness of these helps prepare the public for similar narratives, and journalists to counter them as they happen. Election interference around the globe observed by First Draft has taken three main tracks. This is supported by academic research by Allison Berke, executive director of the Stanford Cyber Initiative, beginning with “the spread of disinformation intended to discredit political candidates and the political process, discourage and confuse voters from participating in elections, and influence the online discussion of political topics”.

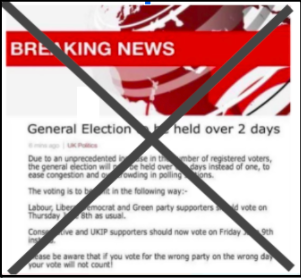

1. Disinformation intended to discredit candidates and confuse the public:

The above example from First Draft’s CrossCheck Nigeria shows how journalists countered misleading claims designed to confuse voters about the fingerprint they could use in Nigeria’s February 2019 general election.

This is a genuine image (above) from Brazil of an intact ballot box on the back of a truck. It was circulated widely in WhatsApp along with a false rumor that ballots had been “pre-stamped” with a vote for Fernando Haddad in the 2018 election (it had NOT been tampered with).

An example (above) of a fabricated BBC news site used to spread false information during the 2017 UK general election.

2. The second track covers the use of information operations to disrupt election infrastructure, including:

- changing vote records and tallies;

- interfering with the operation of voting machines;

- impeding communications between precincts and election operations centers;

- providing disinformation directing voters to the wrong polling place or suggesting long wait times;

- incorrect ID requirements, or “closures” of precincts that do not exist.

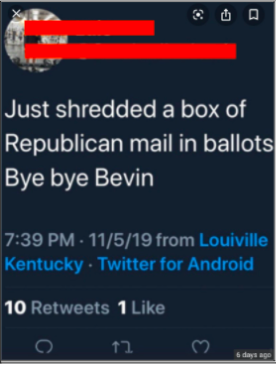

3. This is followed by the undermining of public confidence in electoral processes after an election has taken place.

An example (above) of the false and fabricated claims perpetuated the US stolen-election myth throughout social media.

Many of these tracks to undermine results were most notable in US elections and the January 6 US Capitol riot. The 2020 US election was mired in stolen-election myths online. These included false claims that the use of Sharpie pens had invalidated ballots, and other discredited claims about voting systems, “deleted databases” and “missing boxes.”

While this may seem a world away from Australia, First Draft monitoring at the end of 2021 had already picked up attempts to introduce similar false narratives here. For example, in October 2021, former Senator Rod Culleton tweeted that the “AEC proposes to acquire ‘Dominion Voting Systems’ machines / The AEC is proposing the use of the same Dominion Voting Systems machines to count votes that are being used in America. You know the voting machines where the integrity of these machines is being questioned.” The Australian Election Commission replied that Dominion was “not a provider and won’t be one for the next federal election / electronic voting seems a long way off, let alone a provider for such a thing / Regardless of what was proven or not in US, Aus system so different that comparisons are not useful.”

An unproven claim that has appeared several times in the comment sections of social media monitored by First Draft questioned the provision of pencils in polling booths, and said votes marked in pencil could be tampered with. The AEC explained that pens are accepted alongside the pencils provided in polling stations: “The provision of pencils in polling booths is a requirement of section 206 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. There is, however, nothing to prevent an elector from marking his or her ballot paper with a pen if they so wish. The AEC has found from experience that pencils are the most reliable implements for marking ballot papers. Pencils are practical because they don’t run out and the polling staff check and sharpen pencils as necessary throughout election day. Pencils can be stored between elections and they work better in tropical areas.”

There are also comments that contain inaccurate information about voting methods, such as “you should vote from your computer using your medicare card as id.” However, the AEC website shows that online voting is not an option.

Embracing the fringe to gain status

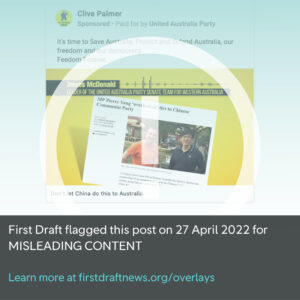

First Draft has reported on how fringe candidates use misinformation to gain outsized online influence, a reach they wouldn’t otherwise have. Their misleading, attention-grabbing campaign videos and posts are viewed by thousands, their campaign messages are plastered on roadside billboards, in letter box drops and even in traditional media advertisements. When they are banned or “deplatformed” from mainstream social media and technology platforms, they simply encourage their followers to move with them to unregulated or anonymous sites, where they regroup. Researchers for The Conversation note the concerns this raises, as “complete online anonymity is associated with increased harmful behavior online.”

Australia has also seen several candidates criticized for using misinformation to gain status online, often tapping into conspiracy theory communities and challenging the existence of Covid-19 or questioning the efficacy of vaccines.The Covid-19 pandemic has provided fringe candidates additional space, attention and audience. They are able to tap into the concerns and anti-establishment sentiment shared by anti-maskers, anti-lockdown supporters and anti-vaccine activists. These voices have turned these messages from the pandemic into political campaigns.

Careful reporting about these candidates is required in order to help reduce information disorder; however, journalists must be aware that covering these stories can have the undesired effect of amplifying misinformation. Therefore, responsible reporting (rather than simply giving media attention and catchy headlines to often-outrageous claims) is key. First Draft provides resources on how to approach reporting on these topics.

Deepfakes, shallowfakes and the power of satire

Hours after a June 2021 leadership spill saw Barnaby Joyce voted in as the new leader of Australia’s National Party and deputy prime minister, an old video in which he appeared drunk was gaining traction on social media. Fortunately, the video was debunked just as quickly as a “shallowfake.”

The 39-second video purported to show Joyce’s slurred rant against the government, but it had been deliberately slowed down to make him sound drunk. Extracting keyframes from the video and conducting a reverse image search, First Draft found the original video. It was posted to Joyce’s verified Twitter account in December 2019 and has been viewed more than 800,000 times since.

The doctored video, meanwhile, had been viewed more than 2,000 times within an hour before it was deleted. First Draft contacted the uploader and was told that the clip was meant to be a work of satire, but having noticed people’s confusion, the uploader would take it down.

As Wardle said, “Satire is used strategically to bypass fact checkers and to distribute rumors and conspiracies, knowing that any pushback can be dismissed by stating that it was never meant to be taken seriously.” Even when it is purely a work of art, satire can be a powerful tool that has potential to do harm, because not everyone in the community might realize it’s meant to be a joke. The more it gets reshared, the more people lose the connection to the original post and fail to understand it as satire. On the other hand, satire can also be an effective means to educate the public on politics – as research into popular comedy shows such as the Daily Show has found. Research into the effect and the ability of the public to understand what is mis- and disinformation via Australian satirical sites is warranted.

In the disinformation field, a video that has had its speed or volume altered to paint someone in a negative light is considered a “shallowfake.” As opposed to “deepfakes” — fake visual or audio materials created by artificial intelligence — “shallowfakes” are products of relatively simple methods, such as tampering with the audio or cutting out several frames, often with malicious intent, as Sam Gregory, program director of human rights nonprofit WITNESS, noted.

Back in 2019, First Draft was already formulating best practices about reporting on shallowfakes and other types of disinformation to avoid further amplification and confusion. While deepfakes like the fabricated “Obama video” were much feared, shallowfakes such as the series of distorted videos of US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi can be more destructive, as they are easy and fast to create.

The visual nature of a deepfake is problematic, because people are less critical of visual misinformation. Compared to memes, misinformation in deepfakes can be even more damaging, as videos can be more believable and subversive. Our advice for those who may be targets of AI-enabled disinformation, particularly during an election — and for those reporting on it — is to have a library of videos ready to show the original where possible.

A patchwork of accountability

The Australian public’s ability to identify mis- and disinformation is further compromised during an election season because of a lack of “catch-all federal laws to prevent lies” in political advertising. Other laws and regulations, such as consumer laws, focus on false or misleading behavior in the promotion of goods and services and do not extend to political ads. The Australian Communications and Media Authority, which regulates broadcasting and telecommunications, has oversight of rules such as the amount of airtime allowed for political advertising, but this does not cover the content of these ads. Australia’s self-regulatory system for commercial advertising includes a complaints process administered by Ad Standards. As ABC FactCheck reported, while Ad Standards hears complaints about misleading ads, these are “only where they target children or relate to food and beverages or the environment.”

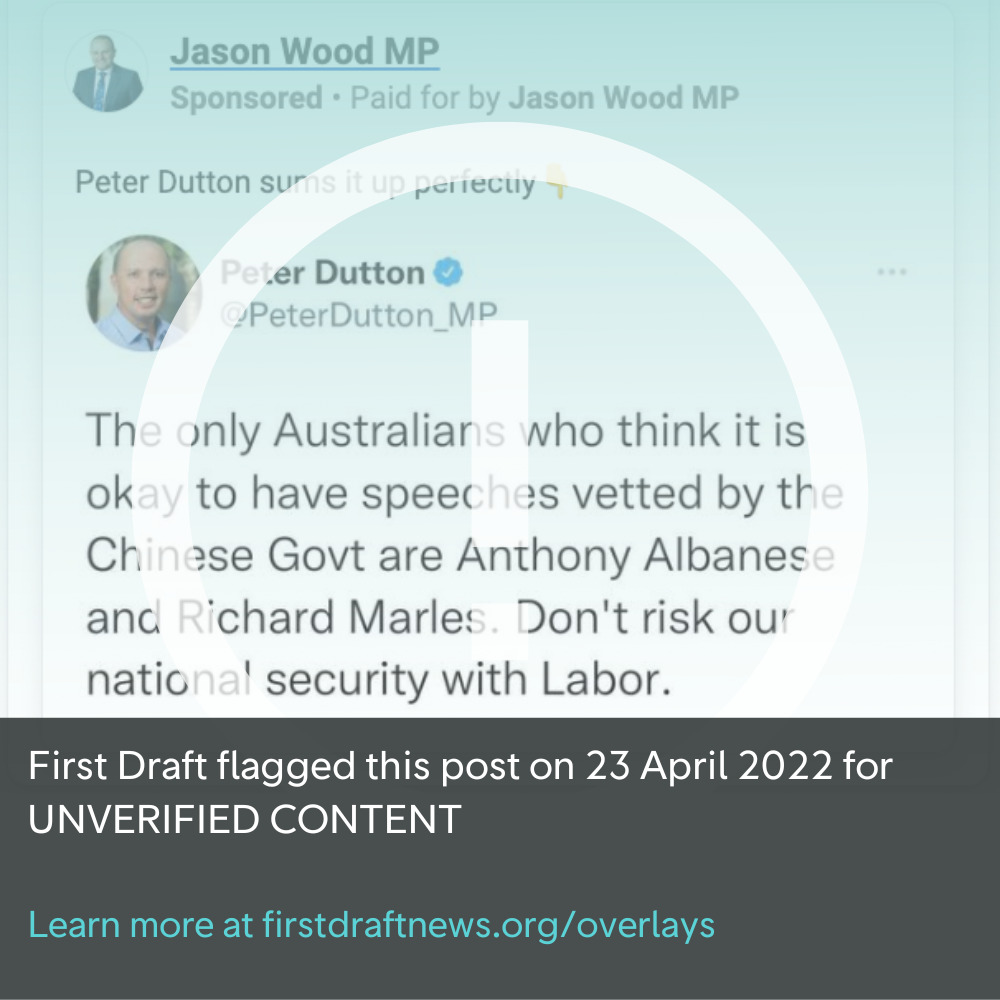

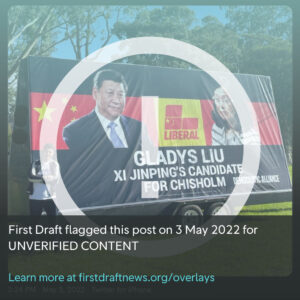

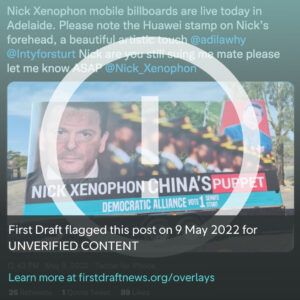

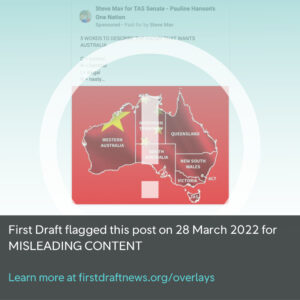

The Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation, which aims to reduce the risk of online misinformation causing harm to Australians, was finalized and adopted during the pandemic by Adobe, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Redbubble, TikTok and Twitter. The code acknowledges the primacy of Australian laws, including for electoral advertising, but otherwise largely exempts “political advertising or content authorized by a political party.” This is perhaps no surprise given the lack of accountability from the patchwork of laws that do not directly target political advertising. First Draft research from monitoring the Facebook Ad Library during the 2020 New Zealand election and referendums was a useful exercise in cataloging the way politicians and activists make use of this space to propagate their agenda and publish their “attack ads.”

The Discussion Paper released with The Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation noted the need in a democracy for any rules or laws in relation to online content to “avoid imposing unnecessary restraints on freedom of speech and expression.” The Discussion Paper made note of further complexities: “People may also simply disagree with opposing political statements and attempt (incorrectly) to label this as misinformation. It is important also to recognize that information is never ‘perfect’ and that factual assertions are sometimes difficult to verify.” To this, First Draft would add that some facts take time, and pressure on journalists to produce quick headlines is at odds with the scientific world’s more measured approach.

Advice for stakeholders

A multi-pronged approach to tackling mis- and disinformation has been in full swing throughout the pandemic — labeling and fact checking, supporting journalists, grassroots campaigns. This showed the developments that can be made by the media and technology companies. As noted in the opening, the crucial role journalists play in countering policial falsehoods as well as slowing down mis- and disinformation should be further developed and supported, rather than the current “he said/she said” and traditional “horse race” reporting during elections. We encourage future outreach programs (from training to research to public media literacy) to help prepare audiences for misinformation.

This report also challenges politicians to consider their roles in the possible spread of falsehoods, blurring of lines and instigating misinformation during campaigns. Also encouraged is further discussion with policy makers and legislators to consider the mis- and disinformation vulnerabilities that arise from the lack of political advertising accountability in Australia.

Further research into Australians’ understanding of definitions and the effect this has is required. As noted above, there is a risk that claims of something as ‘misinformation’ may be a political bias or misunderstanding of the definitions. Yet these same audiences must also have easy access to full context and quality information.

First Draft also recommends more time and resources in newsrooms and media literacy programs be placed on prebunking and misinformation ‘inoculation’. We have an extensive guide available here.

This Australian misinformation election playbook was conducted with support from Meta Australia.

Reference

Allison Berke. Forum Response. Preventing Foreign Interference Is Paramount: The threat of election interference by foreign actors is fundamentally different — and more distressing — than the threat of domestic misinformation. Boston Review https://bostonreview.net/forum_response/allison-berke-preventing-foreign-interference-paramount/

An introduction to live audio social media and misinformation

What does the rise of live, audio-based social media mean for identifying and moderating misinformation? We’ve taken a look at the platforms and their moderation policies, and offer some key takeaways for journalists and misinformation researchers. (Updated January 31, 2022.)

Audio misinformation comes in many forms

One of the challenges of tracking audio misinformation on social media is that audio is easily recorded, remixed and transcribed. During the 2020 US election, one piece of misinformation that went viral was a recording of a poll worker training in Detroit. The recording itself didn’t have evidence of anything nefarious, but it was cut to ominous music, overlaid with misleading text and titled #DetroitLeaks. In 2018, First Draft set up a tip line with Brazilian journalists to monitor misinformation circulating on WhatsApp in the lead-up to that country’s presidential election. Over a 12-week period, 4,831 of the 78,462 messages received were audio files, many containing misleading claims about election fraud. Transcriptions of misleading audio and video were also popular, one example of which was reported to the tip line over 200 times.

What all these cases had in common was that they were extremely difficult to track and verify. Live audio chats, like the kind happening on Clubhouse and its competitors, share these problems. However, they invite live, targeted harassment and are even more ephemeral, often disappearing when the conversation ends. So how can misinformation researchers track this content and how are platforms designing policy around it? A few key themes arise.

Moderating live audio is labor-intensive

We wrote about how audiovisual platforms have been able to sidestep criticism about misinformation even though they are a significant part of the problem. One of the reasons is that audiovisual content takes longer to consume and study. It is also more difficult to moderate automatically. Most content moderation technology relies on text or visual cues that previously have been marked as problematic; live audio provides neither.

It’s no surprise then that Clubhouse and Twitter Spaces rely on users to flag potentially offending conversations (see below for specific policies) as their primary form of moderation, shifting the burden to the people targeted by the content. As for Facebook (now known as Meta), listeners can report an audio room for potential breach of community standards.

Ethics and privacy

Part of the appeal of live audio chats is that they feel intimate. This raises issues of consent and privacy for researchers and journalists who might be interested in using the spaces for newsgathering or tracking misinformation. Clubhouse room creators can record chats; Facebook lets audio room hosts post a recording after the room has ended.

Regardless of the platform’s official policy, journalists and researchers should take care to consider whether it’s necessary to listen in on or use material from conversations in these spaces. Participants might not be aware who is in the room or that their words could be made public. Reporters should also question whether misinformation they hear on the platform merits coverage: Has the falsehood traveled widely enough that reporting on it will not amplify it to new audiences? The size of the room is the only metric available in many cases, as there aren’t shares, likes and comments to help evaluate the reaction and reach the conversation is getting.

The platforms and what we know about their moderation policies

Clubhouse

- How it works: Launched in March 2020, Clubhouse is the app that many have credited with the surge in live audio social media. Speakers broadcast messages live from “rooms” to listeners who tune in and out of these rooms.

- Moderation policy: Part of the reason Clubhouse gained so much attention soon after its launch was its laissez-faire attitude toward moderation. It provided some community guidelines, which emphasize users’ role in moderating and flagging content.

Facebook live audio rooms

- How it works: In public groups, anyone can join a live audio room. Private groups are members only. A room’s host can monetize the room by letting users send Stars — paid tokens of appreciation — or donations.

- Moderation policy: Room creators can remove unwanted participants.

Twitter Spaces

- How it works: The feature provides live audio chat rooms that are public for listeners. Up to 13 people (including the host and two co-hosts) can speak at a time. There is no limit on the number of listeners.

- Moderation policy: If users think a space violates Twitter’s rules, they can report the space or any account in the space, according to Twitter’s FAQ.

Reddit Talk

- How it works: As of this writing, the feature remains in beta. It lets users host live audio conversations in Reddit communities. For now, only community moderators can start a talk, but anyone can join to listen. Hosts can give permission to speak.

- Moderation policy: “Hosts can invite speakers, mute speakers, remove redditors from the talk, and end the talk,” according to Reddit. Community moderators have the same privileges as well as the ability to start talks and ban members from the community.

Discord Stage Channels

- How it works: Discord is a chat app geared toward gamers, letting them find one another and talk while playing. It supports video calls, voice chat and text. In 2021, it introduced “Stage Channels,” a Clubhouse-like function allowing users to broadcast live conversations to a room of listeners.

- Moderation policy: The platform’s community guidelines, last updated in May 2020, read: “If you come across a message that appears to break these rules, please report it to us. We may take a number of steps, including issuing a warning, removing the content, or removing the accounts and/or servers responsible.”

Spoon

- How it works: Spoon, an audio-only live platform, has been around since 2016. It allows users to create and stream live shows where audience members can sit in and participate.

- Moderation policy: Spoon details its community guidelines here. Guidelines on inappropriate language offer an example of how violators are affected. “Some language is not appropriate for users under 18. We reserve the right to consider that when deciding to restrict or remove content including stopping Lives or asking you to change stream titles.”

Quilt

- How it works: It is similar to Clubhouse, but with a focus on self-care.

- Moderation policy: Its community guidelines read: “As a Host, you’re given the ability to mute other participants or move speakers back to the listening section in case anything should happen that takes away from the experience of the group.” Users are invited to report any behavior that doesn’t align with the guidelines to the Quilt team, upon which the platform “may remove the harmful content or disable accounts or hosting privileges if it’s reported to us.”

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

False claims and conspiracy theories about Omicron emerge online alongside the new variant

False claims and conspiracy theories about the new Covid-19 variant Omicron emerged online after the variant was reported by South Africa to the World Health Organization (WHO) on November 24. The WHO said the variant has had a large number of mutations and may present an increased risk of reinfection, but studies on its transmissibility, severity of infection (including symptoms), performance of vaccines and diagnostic tests, and effectiveness of treatments are still underway.

Conservative influencers are circulating claims that the variant is part of a government plan to oppress unvaccinated populations.

In a Facebook Live that was broadcast November 30, conservative radio show host Ben Ferguson alleged that the government is using the Omicron variant to “fearmonger” and to perpetuate “Covid racism” by separating society into those who are vaccinated and those who are not. Ferguson also claimed in the video, which had been shared over 600 times and garnered over 26,000 views as of December 3, that the government is pushing for people to get booster shots through the purported fear mongering.

Other conservative influencers, including Ben Shapiro, Chuck Callesto, Kim Iversen, and Candace Owens, said that the Omicron variant was being used to enforce another lockdown and frighten people into getting vaccinated. One post from Owens implying Covid-19 was being used to “usher in a totalitarian new world order” was shared over 44,000 times on Facebook; the original tweet garnered over 19,000 retweets.

One popular false narrative from supporters of ivermectin has been that the Omicron variant was either made up or deliberately released by proponents of the Covid-19 vaccine in Africa. According to this conspiracy theory, up until last week the African continent had been successful in fending off the pandemic because of the prevalent use of the “miracle drug” ivermectin despite its low vaccination rate. According to the Food and Drug Administration, currently available data shows that ivermectin is not effective in treating Covid-19.

Perhaps one of the most prominent examples came from Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), who has frequently promoted QAnon and other conspiracy theories. In a series of tweets November 27, she amplified this conspiracy theory, falsely claiming that “many clinical trials have proven Ivermectin to be a very effective safe & cheap treatment against #Covid”.’ These tweets have been shared thousands of times.

In Australia, a number of rumors have also been circulating. Public Facebook posts that mention Omicron with the most interactions between November 22 and 29 are from MP George Christensen, far-right figure Lauren Southern and anti-lockdown activist Topher Field. Each of these posts gained thousands of interactions within 24 hours.

One of the most popular false claims is that Omicron appears “ahead of schedule,” citing a chart purportedly from the WHO, the World Economic Forum (WEF) and Johns Hopkins University with a predetermined “plan” for releasing the variants. Spokespeople from the WHO, WEF and Johns Hopkins told First Draft in email statements that they are not associated with the image. The chart has circulated online since at least July and has also been debunked by Reuters Fact Check, Snopes and India Today.

Other false claims among the Facebook posts include calling the variant “planted” and blaming vaccinated people for the variant. One claim also falsely declared that vaccines weakened people’s immunity. Similarly in a Telegram group with more than a million members, one post falsely stated that the Covid-19 vaccines are what caused Omicron.

A prominent conspiracy theory links the new variant’s emergence to Ghislaine Maxwell’s sex-trafficking trial, which started in the US on November 29. For example, one comment on Topher Field’s post shares a screenshot of a post from US conservative influencer Rogan O’Handley, or DC Draino, that reads in part: “If you think the Omicron hysteria popping up 2 days before the Ghislaine Maxwell trial starts is just a ‘coincidence,’ then you don’t know who she was trafficking underage girls to.” Similar comments are also found on George Christensen’s post and a Telegram post, which also ties Omicron to the QAnon conspiracy theory of a “tyrannical peadophile CV19 government.”

Another conspiracy theory states that the letters “o,” “m” and “i” in Omicron stand for “occlusion” and “myocardial infarction,” linking without evidence the new variant to the rare side effects, such as a rare blood clotting disorder and myocarditis, that some Covid-19 vaccines have caused in a small number of people.

Our research finds a notable data void on Omicron, even though assessments take time. The deficit in data needs to be filled with credible information from trusted sources and facilitated by precise, accurate reporting as soon as possible to stop the spread of baseless or false information about the variant and the pandemic. — Esther Chan, Kaylin Dodson, Keenan Chen

Misinformation accompanies US expansion of boosters

As the United States is poised to roll out its Covid-19 vaccine booster program for all adults, misleading information on social media around this latest development is likely to become the focal point of the next round of vaccine misinformation.

Already, false narratives about additional vaccine shots creating a new wave of infections and newer variants of the coronavirus elsewhere in the world have resurfaced. For example, Robert Malone, a Covid-19 vaccine skeptic known for his role in contributing to the development of mRNA vaccine technology but has since been promoting claims of the vaccine causing miscarriage, the vaccine not being authorized and other false information, is a major promoter. Malone, who has a sizeable audience through Twitter and his amplifiers in the right-wing media ecosystem, has posted multiple tweets in the past few days describing the vaccine as “leaky”.

Other pandemic skeptics and vaccine deniers used the rise of case numbers in Western Europe, where many countries had already given out extra doses, as purported “proof” of booster shots leading to new and more infections. Some social media posts pointed to Gibraltar, the highly vaccinated British territory that just announced a new round of Covid-19 restriction measures because of increasing infection numbers.

A blog post by an anti-vaccine Substack user popular among like-minded social media users claimed that neighbouring countries where booster shots have not yet begun or kicked into high gear had less of a spike in cases than Gibraltar. It was retweeted by Jeffrey A. Tucker, a libertarian writer and president of the Brownstone Institute, a newly founded publication that has been promoting ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine and other unproven Covid-19 “cures.” — Keenan Chen

Austria’s lockdown for unvaccinated people falsely compared to Nazi policies

False comparisons have again been drawn between Nazi Germany and Covid-19 pandemic measures, this time prompted by the introduction of a lockdown for people in Austria who are not fully vaccinated.

About two million people in Austria, or one-third of the population, were placed in lockdown on Monday, November 15, with the country facing a surge of infections. Austria has one of the lowest vaccination rates in Western Europe, with anti-vaccine sentiment encouraged by the far-right opposition Freedom Party.

In the hours after the announcement of the lockdown, the following statements were made in the Facebook comment sections of Australian news publishers with millions of followers, on subreddits with millions of members, and in Australian Telegram groups with thousands of members.

There were many references to Austria as Adolf Hitler’s birthplace and the rise of Hitler’s Nazi Party in Germany, with comments claiming history was repeating itself.

Others commenters falsely claimed unvaccinated people would be sent to “camps”, “rounded up” and vaccinated, or forced to wear signs like yellow stars, as Jewish people were forced to under Nazi rule. Some referred to “the Final Solution” when discussing the lockdown, while others made antisemitic statements and claimed the lockdown was a sign that Austria is embracing fascism.

Comments that misconstrued the role of vaccines and therefore the relevance of the lockdown were common. Some falsely stated that the vaccines don’t work and that unvaccinated people were being blamed for rising case numbers. Research shows that vaccinated people are less likely to contract and spread Covid-19, and less likely to require hospitalization.

There were misleading attempts to link Austria’s lockdown with pandemic measures in Australia, such as claiming that Victoria’s controversial pandemic laws would give the state’s premier power to implement a similar lockdown. The false claim was also made that Australia is building camps for the unvaccinated, as debunked by AAP Fact Check here.

As previously reported by First Draft, opposition movements to Covid-19 vaccination and other public health measures have frequently sought to link aspects of the pandemic with Nazi indoctrination and policies. These types of comparisons are unfounded and irrelevant: Jewish people and others, including Romani and gay people, were persecuted and killed based on ethnicity and sexuality. — Lucinda Beaman

Disinformation actors share misconstrued narratives about coronavirus spike protein to push vaccine skepticism

Vaccine misinformation concerning the coronavirus spike protein has again picked up in recent days. Vaccine skeptics and deniers have weaponized this medical term to deter people from trusting Covid-19 vaccines, which have been proven effective and safe.

Natural News, InfoWars and other well-known disinformation actors intentionally misinterpreted a recently published paper on a potential mechanism of how full-length spike protein found on the coronavirus could diminish a person’s DNA repair system — especially in older people — and obstruct their adaptive immunity. Yet these disinformation actors baselessly claimed the vaccine itself sends spike protein into a recipient’s “cell nuclei” and “suppresses DNA repair engine.” This narrative is misleading because “mRNA never enters the nucleus of the cell where our DNA (genetic material) is located, so it cannot change or influence our genes,” reads a CDC fact sheet.

A recent Wall Street Journal report on scientists looking into how the mRNA-based vaccines could trigger myocarditis, pericarditis or other heart inflammation symptoms in a small number of recipients also drew attention from vaccine and pandemic skeptics. One of the many theories researchers are considering, according to the report, is the possibility that the spike protein, which is produced by the body after receiving the vaccine, might share similarities with ones found in the heart muscle, tricking the immune system into attacking the heart muscle. Still, recent studies have confirmed these cases to be extremely rare and mostly benign.

Additionally, an FDA document on recommending the vaccine for children ages 5-11 was taken out of context by these actors to justify their anti-vaccination stance. While experts with the FDA theorized a scenario where, if Covid-19 transmission were low, the number of “myocarditis-related hospitalizations in boys in this age group would be slightly more than Covid-related hospitalizations,” they still confirm the benefits of vaccination outweighing concerns about side effects. Yet some highly engaged social media posts misleadingly claim that the government has admitted there will be more myocarditis hospitalizations than those for coronavirus. — Keenan Chen

Facebook comment sections rife with misinformation following Pfizer’s Covid-19 antiviral pill announcement

Last week Pfizer published interim trial results for its experimental Covid-19 antiviral pill, Paxlovid, which the company said reduced the chance of hospitalization or death for some adults by almost 90 per cent. The US pharmaceutical giant’s analysis included 1,219 adults who had been diagnosed with mild to moderate Covid-19 and who had at least one risk factor for developing severe disease.

First Draft examined Facebook posts by Australian news publishers covering this story and found that misinformation and misunderstandings flourished in the comment sections, with potential audiences in the hundreds of thousands over the past week.

Facebook users questioned the efficacy and relevance of Covid-19 vaccines in light of the emergence of the antiviral pill, questioning the need for the pill if the vaccine is effective. Others shared the misleading claim that the Covid-19 vaccines are as not effective as reported if a pill could cure the disease or alleviate the condition. While the antiviral pill may be helpful for those diagnosed with Covid-19, vaccines reduce a person’s chances of contracting it.

Many commenters incorrectly drew links with the anti-parasitic medication ivermectin, describing the Pfizer antiviral treatment as “Ivermectin renamed,” “like ivermectin but more expensive” and “Pfizermectin.” The comment sections became a forum for the misleading promotion of ivermectin as a “safe and effective,” “tried and tested” and “successful” treatment for Covid-19.

The antiviral pill and ivermectin are not the same. The WHO recommends against using ivermectin in patients with Covid-19, except in the context of a clinical trial. Misinformation around ivermectin as a Covid-19 treatment has led to real-world harm.

Negative sentiments about profits to be made from the medication were also common, with comments speculating this is a new stream of revenue for Pfizer after making the vaccines.

First Draft reported on similar narratives circulating in October after the Merck antiviral pill molnupiravir was approved in the UK. Explainer stories and prebunks addressing the respective roles of Covid-19 vaccines and treatments could prevent data deficits that lead to the spread of misinformation.

Discussions taking place in comment sections have the potential to shape attitudes and behaviors. Previous First Draft research has highlighted a need for greater content moderation by publishers as well as the gap between Facebook’s misinformation policies and actual outcomes. — Lucinda Beaman

Videos of anti-vaccine healthcare workers being removed from jobs reinforce misleading claims

Several videos of anti-vaccine medical workers recording themselves being suspended or fired from their jobs at healthcare facilities have generated significant interest in the past few days.

Most physicians and healthcare workers in the United States have received Covid-19 vaccines. In a June survey, the American Medical Association reported that 96 percent of physicians have been fully vaccinated against Covid-19. And in earlier surveys of thousands of members, the American Nurses Association and the American Association of Nurse Practitioners reported that most of their members had received the vaccines.

In one video, which had been viewed over 7 million times on Twitter before the account was suspended, a San Diego-area nurse filmed herself being escorted out of a medical facility after refusing to take the Covid-19 vaccine for religious reasons. The nurse told a San Diego television station she believed her “God-given immune system” was good enough to fight Covid-19. In addition to its spread on social media and amplification by influencers, the video also received coverage from news organizations and digital outlets such as The New York Post, The Daily Mail, Newsday and the right-wing One America News Network.

Similarly, in another video, a healthcare worker at a Los Angeles hospital was escorted out for his refusal to receive what he called “the experimental vaccine,” a long-lasting misinformation narrative. The video, shared by a Facebook Page based in South Africa, has received at least 3.5 million views since last weekend. These viral videos once again show how misleading claims from healthcare workers — even if they have no training in epidemiology or vaccine science — can resonate because due to their profession, they are perceived as experts. — Keenan Chen

Boost in vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories as Australia prepares to roll out Pfizer booster for adults

Australia will begin offering Covid-19 vaccine booster shots to eligible members of its adult population on November 8. News that the country’s medicines regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), had provisionally approved the Pfizer vaccine as a third dose was met with skepticism, misinformation and conspiracy theories online. Shared as posts and comments on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts in Australia, these narratives had potential audiences in the hundreds of thousands in the past week.

Some social media users suggested the need for Covid-19 booster shots means previous vaccination efforts have failed. For example, on an Instagram post by the TGA, one commenter asked whether the approval of boosters means the TGA is admitting the two doses are ineffective. On Facebook, a Queensland-based nutritionist made the misleading claim that “the earlier shots haven’t truly worked.” On Facebook and Instagram, comments on articles posted by news organizations included similar questions and statements.

Conspiracy theories that Australian politicians, the TGA and US pharmaceutical companies are recommending booster shots for financial gain were common, including claims of “kickbacks,” “political bribes,” scams and profiteering. Some of these themes were also shared in cartoons and memes.

Many of the examples feed into a broader false narrative that Covid-19 vaccines don’t work or are unnecessary. The misleading claims were spreading on social media shortly after the government announcements, and it was clear there were data deficits regarding the recommendation for booster shots.

It would be helpful for media organizations and other communicators to pair news stories with explainers that address people’s potential questions and concerns around Covid-19 vaccines — in this case, why additional doses may be necessary. — Lucinda Beaman

Headlines about Australian actress’ stroke after vaccination fail to mention rarity of the conditions

News headlines about a UK-based Australian actress who suffered a stroke “after getting Covid vaccine” or “after getting the AstraZeneca Covid vaccine” overly emphasized a single incident without providing important context about the rarity of such reaction. The family of actress Melle Stewart, who had a stroke two weeks after her first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine in early June, said on a GoFundMe page that she was diagnosed with vaccine-induced Thrombocytopenic Thrombosis (VITT), or Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS). Despite her misfortune, the family added that VITT is a “very rare side effect of this particular vaccine” and that Stewart “has been and continues to be an advocate for vaccination”.

Without including statistics to illustrate the unlikely event of VITT, or TTS, following the AstraZeneca vaccine, these headlines risk exaggerating the probability of people who are otherwise healthy and relatively young like Stewart developing serious health issues after their vaccination. According to Australia’s medicines watchdog the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), as of October 21 “there have been 156 cases of TTS assessed as related to Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) from approximately 12.6 million vaccine doses”.

British far-right activist Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, who goes by Tommy Robinson, recently called the Australian government “totalitarian” over the country’s Covid-19 restrictions and lockdown policy. Robinson shared a link to a Daily Mail report about Melle Stewart on Telegram saying severe reactions to Covid-19 vaccines are not as rare as reported. The post has been viewed over 35,000 times after being shared by Robinson with his 137,000 followers.

Australian celebrity chef and conspiracy theorist Pete Evans, who is followed by nearly 50,000 users on Telegram, reposted a post from a popular conspiracy-fueled website that focused on the presumed and unproven correlation that since Stewart was healthy, her stroke would have been caused by the vaccine.

A post in a Telegram channel dedicated to anti-lockdown protests falsely stated that the AstraZeneca vaccine would cause stroke. While clots in the arteries following vaccination can cause stroke, the probability for AstraZeneca recipients to develop VITT or TTS is extremely rare. The TGA also said the risk of TTS is not likely to be increased in people with a history of ischaemic heart disease or stroke.

News reports about the reactions well-known figures such as celebrities and influencers have following vaccination can unwittingly be used as a powerful vector in promoting false information and conspiracy theories, as First Draft pointed out in a campaign against “misinfluencers”. An iInaccurate, and in this case distasteful, comparison by Australian actress Nikki Osborne between a purported workplace vaccine mandate and a meme showing Harvey Weinstein’s pursuit of actress Lindasy Lohan can work to vilify Covid-19 vaccines and hamper the government’s vaccination efforts. — Esther Chan

Vaccine skeptics seize on death of Colin Powell to spread misinformation

Almost immediately after the October 18 death of Colin Powell became public, vaccine and pandemic skeptics started claiming that the Covid-19 vaccine, which the former US Secretary of State had received, was ineffective or even contributed to his death.

While Powell, who had also served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other top government posts, died from Covid-19 complications, the 84-year-old had also been battling multiple myeloma, a white blood cell cancer that weakened his immune system.

But on Gab Trends, a news aggregation site run by the far-right social site Gab, a headline claiming Powell “died of #COVID19 despite being vaccinated twice” was placed front and center.

A TikTok video commenting on Powell’s death, with embedded text that reads, “SO TELL ME HOW THE VACCINE SAVE PEOPLES LIVES!!! WAKE UP,” was shared over 4,300 times. And in a Facebook post that’s been shared over 500 times, Pamela Geller, an anti-Muslim provocateur, used Powell’s death to advance the conspiracy theories that the Covid-19 vaccine itself was causing Covid infections.

The phenomenon of attributing prominent public figures’ illnesses or deaths to the Covid-19 vaccine has been common since the introduction of the vaccine late last year. In January, posts alleging that baseball great Hank Aaron was killed by the Covid-19 vaccine went viral on social media. These claims were debunked by multiple outlets.

But at the same time, some media watchers also disagreed with mainstream media’s coverage of the event. For example, Mathew Ingram of the Columbia Journalism Review criticized a tweet by the Associated Press as “doing the anti-vaxxers work for them!”

“Here’s a perfect example — mentions COVID, but doesn’t mention anything about blood cancer or other co-morbidities, not in this tweet and not in either one of the other two tweets in this thread,” Ingram tweeted. — Keenan Chen

Anti-vaccine networks misconstrue preprint study into vaccine breakthrough cases

Misleading narratives based on an August 25 preprint study (yet to be peer reviewed) from Israel are circulating online, with vaccine skeptics misconstruing the study’s conclusions about immunity arising from Covid-19 infections to suggest vaccines are unnecessary or even harmful.

The preprint study concluded that people who had been vaccinated with two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine but had not previously tested positive for Covid-19 had a 13-fold “increased risk for breakthrough infection with the Delta variant compared to those previously infected.”

First Draft monitored the following misleading claims spreading in English in the United States, Germany and Australia on Facebook, Telegram, Twitter and BitChute. One Telegram post alone received more than 140,000 views in two weeks.

Some social media users wrongly suggested being vaccinated against Covid-19 increases one’s risk of contracting the disease. Others misconstrued the results of the study by comparing the outcomes for vaccinated people directly with unvaccinated people, as opposed to those who had already built up immunity through infection.

Posts on Telegram and Twitter included a falsified “transcript” from a Supreme Court of New South Wales hearing into vaccine mandates, falsely quoting an expert witness as answering “yes” to the question: “Is it true that double-vaccinated people are 13 times more likely to catch and spread the virus?”

A belief that the Israeli study suggested people would be better off recovering naturally from Covid-19 than receiving a vaccine was also evident, as was a belief that vaccines were not necessary.

The study concluded that “individuals who were both previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 and given a single dose of the vaccine gained additional protection against the Delta variant.” Experts responding to the study and quoted by Science stressed that infection among unvaccinated people would “put them at significant risk of severe disease and death.”

As reported by First Draft, the highly adaptive nature of anti-vaccination networks has been noticeable through the recycling of old misinformation narratives. In this case, some of the misleading narratives arising from the Israeli study echo false claims from 2020 that having a seasonal flu vaccine would increase a person’s chances of contracting Covid-19. — Lucinda Beaman

Anti-vaccine narratives following New South Wales’ reopening appropriate Nazi references

As the Australian state of New South Wales gradually comes out of lockdown, some anti-vaccine and anti-lockdown activists have adopted Nazi references to voice their opposition to measures such as digital vaccination certificates (also known as “vaccine passports”) and relaxed restrictions only for fully vaccinated people.

Opposition movements to Covid-19 vaccination have frequently used Nazi references to claim governments and health officials are imposing authoritarian measures on the population, even by high-profile figures with millions of followers. Most recently, American podcaster Joe Rogan was slammed by a Holocaust survivor for resharing a video to his 13.3 million followers on Instagram, which showed clips related to Covid-19 and authoritarianism, including clips of Nazi imagery, interspersed on top of a narration from Rogan claiming “American freedom” would slip away if vaccine mandates were implemented. Around the world, anti-vaccine protests have featured imagery that implied protesters were being persecuted like the Jewish during the Third Reich.

This type of comparison is unfounded, as Jewish people and others such as the Romani or gay people were persecuted for their race and sexuality, and not over a personal choice such as vaccination, and were actively discriminated against as an exclusionary policy, compared to vaccination as an inclusion and protection of life policy. Moreover, the comparison trivialises and dishonours the memory of those who suffered.

On October 11, restrictions in New South Wales were relaxed for fully vaccinated residents after an over-100-day lockdown. These so-called “new freedoms” carry the condition that people must provide proof of vaccination and check in at venues, prompting some social media users to label the day “Apartheid Day” instead of the popular term “Freedom Day.” Users compared the vaccination evidence to the yellow Star of David that Jewish people were required to wear during the Third Reich.

An Australian “mom influencer” who has over 7,400 followers on Instagram posted a photo of herself and her three children each wearing a yellow Star of David that bore the words “No Vax.” In the lengthy caption, she wrote that she has been deemed a “threat” and that history was repeating itself. She locked her account after a public outcry and denied comparing the lockdown to the Holocaust in a statement to Australian media outlet Pedestrian TV. The influencer has referred to the Holocaust in several anti-vaccine posts in the past; for instance, she posted an image of herself a few days prior referencing Nazi-era prisoner uniforms with the hashtags #historyrepeatsitself and #whichsideareyouon. She also mentioned Anne Frank and the Nazis in a post discussing the social divide over vaccination, claiming to be “praying for a great awakening.”

A video purportedly showing Victorian police officers questioning a person about their participation in anti-lockdown protests based on their social media activity has garnered over 2.6 million views since being posted by right-wing activist Avi Yemini on Twitter on October 10. The video alongside Yemini’s caption “Australia has fallen” has prompted comments from other right-wing figures as well as social media users comparing Australia to Nazi Germany. One account associated with the anti-CCP Himalaya movement commented with a meme showing a Nazi swastika made of syringes, implying an equal comparison between Nazi-era measures and efforts fo vaccinate people. The same image has been seen elsewhere, such as at an anti-vaccine protest in Utah. Other comments about the video said Australia is “about to be” Nazi Germany and compared Australia to depictions of totalitarianism in George Orwell’s 1984, especially elements of pervasive government surveillance and INGSOC, the ideology of totalitarianism depicted in the novel. — Stevie Zhang

Inaccurate claims and conspiracy theory about new Covid-19 medicine

The announcement of medicines that may be able to prevent or treat mild or moderate cases of Covid-19, namely US pharmaceutical giant Merck’s oral antiviral drug molnupiravir and British-Swedish company AstraZeneca’s antibody cocktail AZD7442, has led to misleading or false claims about their efficacy and potential safety issues. There were also inaccurate comparisons made with the Covid-19 vaccines, as well as a conspiracy theory about a purported collusion between governments and pharmaceutical companies.

An Australia-based Telegram channel referred to an episode of a US conservative podcaster’s show with a self-proclaimed former health economist, who promoted an unproven claim that molnupiravir can cause “genetic manipulation” and cancer.

However, the genetic changes in fact happen in the machinery that reproduces the coronavirus: As the developers of the treatment explain, the virus will now be barred from multiplying thanks to errors introduced to the medicine’s genetic code. While data from molnupiravir’s clinical trial has yet to be peer reviewed and there is a lack of details about potential side effects, there’s no indication so far of any cancer risk.

Others compared Merck’s new Covid-19 medicine to the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin. For example, Australian MP Craig Kelly asked on Telegram why not just use the “original (Ivermectin)”.

Merck, which developed ivermectin, released a statement earlier this year clarifying that there was no evidence for the medication’s clinical efficacy in Covid patients.A conspiracy theory that pharmaceutical companies are in cahoots with governments to profit from the new Covid-19 drugs was also popular on multiple platforms. For instance, one tweet purports to compare molnupiravir and ivermectin and seeks to highlight that the only reason the former would be approved is because it is “funded by Fauci.” A report by right-wing blog ZeroHedge says molnupiravir is sold at a price that represents a markup of 40 times its production cost, and that the US government helped fund it. The report ZeroHedge referred to only took into account the cost of the ingredients but not other costs such as clinical trials and research and development.

The development of molnupiravir began at Emory University in 2013 — seven years before the Covid-19 pandemic — with funding from a Department of Defense agency and NIAID, headed by Dr. Anthony Fauci. Clinical trials from 2020 onward found the medicine effective in keeping Covid-19 symptoms under control, but funding from US government agencies was not intended exclusively for the development of a Covid-19 medicine. — Esther Chan